Electra Havemeyer Webb was drawn to vibrant color in all media. Although other distinguished 20th-century collectors were stripping furniture of the original paint to create a clean and pristine appearance on their antique pieces, Mrs. Webb was amassing all types of decorative surfaces, and preserving the finish, whether intact or not. The fine, folk, and decorative art objects on exhibition here represent the full spectrum of primary and secondary colors as well as dazzling metallics that define Mrs. Webb’s bold and eclectic taste.

Color draws us to an object. Historically, color serves as a way to help the viewer differentiate between similar items. In fact, connoisseurship relies on the visual recognition of subtle color variations to separate like forms produced by different makers just as companies today use color in branding their products. In the past, color has also been carefully and cleverly used as a means to disguise the appearance of common substances such as pine, pewter, and earthenware in imitation of more expensive materials like mahogany, silver, and porcelain for status-conscious consumers. This is evident in furniture, metalwork, and ceramics in the Shelburne Museum collection.

Color in Music

A playlist by the Vermont Symphony Orchestra

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by The Donna and Marvin Schwartz Foundation and the Barnstormers at Shelburne Museum.

Edouard Manet (French, 1832 83)

The Grand Canal, Venice, 1875

Oil on canvas, 23 1/8 x 28 1/8 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972 69.15

In 1875, Manet painted this view on the Grand Canal, which H. O. Havemeyer purchased for his wife Louisine 20 years later. She was particularly fond of the picture and changed its name to Blue Venice. Mrs. Havemeyer wrote that her friend Mary Cassatt “congratulated us when we bought this picture, saying she considered it one of Manet’s most brilliant works; it was so full of light and atmosphere and expressed the very soul and spirit of Venice.” Her daughter Electra Havemeyer Webb inherited Blue Venice, which hangs in the living room of her New York City apartment, reinstalled in Shelburne Museum’s Memorial Building.

The myth of Venice was largely established by visiting artists during the 19th century. The atmospheric chemistry between sky and sea, light and water inspired epoch-making works that provided crucial impulses to the development of modern art. Manet commented that this play of light reminded him of champagne bottles floating bottom up and it was precisely this sparkling effect he tried to capture on canvas.

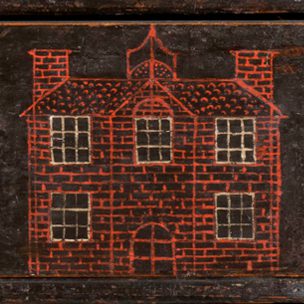

Unidentified maker (Probably rural Massachusetts)

Harvard Chest, 1700 25

Painted pine and brass, 43 3/4 x 38 7/8 x 20 3/4 in.

Gift of Katharine Prentis Murphy and Edmund Astley Prentis, 1956 694.8

This chest is one of six similar surviving case pieces from Massachusetts. Its decorative scheme emulates expensive “Japanned” furniture—a treatment inspired by oriental lacquer work and fashionable in colonial America during the William and Mary period (1690-1720). The red, white, and yellow painted decoration on this chest covers what appear to be five drawer fronts, although there are really only two. The focus of the façade is a crimson sunrise embellishing each drawer face, surrounded by fanciful flowering vines, and stairways leading upwards to nowhere. The architectural renderings of the pair of two-storied brick-faced buildings with cupolas were once believed to represent structures at Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. For that reason, this and the handful of related painted boxes became known as “Harvard chests.” The design source for these particular edifices is more apt to have been a product of the artist’s imagination rather than any academic structure.

G.A. Dentzel Carousel Company (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1867 1909)

Carousel Tiger, ca. 1902

Carved and painted wood, 50 3/8 x 14 ½ x 77 in.

Museum purchase, 1951 392.18

The striking color orange is represented in several different media in the Museum’s collection and is used realistically as it appears in nature. The Circus Building features 40 wooden merry-go-round figures made between 1895 and 1902 by the Gustave Dentzel Carousel Company of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dentzel’s menagerie figures, like this tiger, set the standard for quality, boasting detailed, anatomically correct carving, and exquisite painting. The survival of all 40 animals with original surface is rare—most amusement parks maintained their carousels by covering them with garish and inexpensive “park paint.”

William Matthew Prior (American, 1806 73)

Mrs. Nancy Lawson, 1843

Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 25 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1959 265.34

Shown fashionably dressed with stylish accessories and an open book, denoting her literacy, Nancy Lawson radiates beauty and placidity. Her striking garment could have been dyed Sheele’s or Emerald green, both highly toxic synthetic pigments available at the time. The sitter’s costume is a form-fitting bodice with full sleeves below the shoulder—a style that was still considered fashionable in 1843. The space at the neckline is filled in with a chemisette, a popular modesty piece of the period. On her head she wears a white indoor cap, an essential accessory for married women. It is obvious from both the dress and the interior setting that Mrs. Lawson was a substantial figure in her community.

Hattie Carnegie (New York, New York, 1889–1956)

Evening Gown, 1955 60

Silk, metal, glass, and sequins, 56 x 34 x 45 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from the Estate of J. Watson Webb, Jr., 2000 24.44

The clothing Electra Havemeyer Webb wore during the last 20 years of her life included 20 custom-made dresses designed by New York couturier Hattie Carnegie. Known for her simple yet stylish creations that clothed her clients from “head to hem,” Carnegie seems to have been Mrs. Webb’s favorite maker of special occasion evening wear. This chartreuse dress features several characteristic Carnegie elements including a beautiful fabric enhanced by a rich, low-key color and cutout design accented with simple gold cord and sequin clusters. It was worn by Mrs. Webb at a 1953 debutante party for her granddaughter, Electra Bostwick.

Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory (British, 1745 84)

Pair of Chelsea Swan Tureens, 1752 58

Porcelain, 10 7/8 x 11 3/4 x 16 3/4 in. & 18 3/8 x 10 3/8 x 18 3/8 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1961 184.92.1&2

These magnificent tureens produced by the Chelsea Factory, established outside of London in 1745, are remarkable for their mastery of a new and exciting material that today we take completely for granted. Chinese porcelain arrived in Europe by the 14th century and was greatly admired but very expensive to produce. For 300 years the courts of Europe were competing to be the first to simulate this white translucent material from the East, which today we call china. The royal manufactory at Meissen, Germany, was the first to invent hard paste porcelain in 1708. The recipe was kept top secret, and experiments continued in other countries.The Chelsea porcelain factory discovered its own unique soft paste formula containing silica, alumina, and lime. These large-as-life birds are functional table ornaments that pay homage to the monumental animal sculpture for which Meissen became famous while also celebrating London’s royal fowl. The swan frequently found its way to the table and was served at banquets, as recipes written in Chaucerian English testify.

Attributed to John Goddard (American, 1724-85)

Corner Chair, 1760-70

Mahogany and cloth, 30 7/8 x 27 3/4 x 29 1/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from John Kenneth Byard, 1957-532.1

The deep red, naturally close-grained mahogany from which this elegant chair was made probably came from the Dominican Republic. Lumber from this country has long been prized for its color, figure, and stability. The roundabout, or corner chair, was introduced in America in the early 18th century and was one of the most comfortable seats available for a desk. Its two backrests are set at right angles, and its broad, low arms allowed a writer to draw the chair under the fall front of a secretary desk while retaining elbow support. The serpentine shape of the arms, interlaced design in the back splats and the distinctive carving style of the ball and claw feet with undercut talons confirm a Newport origin. This piece is attributed to John Goddard because it closely resembles a corner chair he made for wealthy merchant John Brown, now in the Nicholas Brown house in Providence, Rhode Island. Both are masterpieces of integrated sculpture carved from the solid.

L.W. Cushing and Sons (Waltham, Massachusetts, active 1867–1933)

Cow, 1875 85

Copper and gold leaf, 17 x 28 in.

Bequest of Harry T. Peters, Jr., 1982 5.413

Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb was one of America’s earliest and most prolific collectors of weathervanes and accumulated examples in various styles and materials. Farmers were likely to choose weathervanes depicting sheep, pigs, and cows for their barns because their attention was focused on livestock. When American manufacturing techniques and marketing methods matured during the second half of the 19th century, weathervanes were produced commercially. Master carvers created the wooden pattern on which the sheet copper was hammered to create the full-bodied form. The smooth surface of the metal retained the gilding that customers wanted to last as long as possible. The quilted surface patterning evident here was caused by overlapping the gold leaf squares that were then applied to the copper with a lead-based oil.

Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company (New York, New York, 1892–1902)

Tiffany Armchair, 1890 91

Carved and gilded wood with silk and glass, 33 15/16 x 25 1/16 x 23 in.

Gift of George G. Frelinghuysen II, 1974 14.7

The Shelburne Museum collection includes nine rare examples of furniture that Electra Webb’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Henry O. Havemeyer, commissioned from Louis Comfort Tiffany and Samuel Colman for their new residence at 66th Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City, built in 1888. The music room, which was one of the more public spaces in the house and the location of numerous musicales frequented by the cultured elite of New York, was decorated in reference to Far Eastern designs. Among the furnishings was this armchair, part of a larger suite consisting of three settees, six arm and side chairs, and two unusual tables. The set embodies the prevailing Art Nouveau style in the intertwined naturalistic plant and flower forms carved in low relief. The denseness of the decoration contrasts with the delicate tapered legs with reeding, terminating in feet composed of colorless glass balls held by brass paws. As much attention was paid to the finish as to the pieces themselves. “After the carving had been done, a fine gold leaf was applied and then slightly rubbed off leaving the relief a little bare, which made it look old and as if it had been handled for many years…”

Tiffany & Co. (New York, New York, est. 1837)

Wagner Palace Car Co. Loving Cup, 1899

Cast and chased silver, 13 1/2 x 13 3/8 x 13 3/8 in.

Gift of William Seward Webb, Jr., 1952 300.2

This Tiffany & Co. masterpiece was owned by Electra Havemeyer Webb’s mother- and father-in-law, William Seward and Lila Vanderbilt Webb. The 25-pint, three-handled cup was presented by the 4,000 employees of the Wagner Palace Car Company to William Seward Webb (1851-1926) upon his retirement from the presidency of that firm on December 31, 1899. In competition with the Pullman Palace Car, both companies offered similar versions of opulent sleeping and drawing room compartments with folding upper berths and seats that could extend into lower beds.<br/><br/>Custom-made by Tiffany & Co., the trophy’s three sides feature a portrait of Dr. Webb, an unidentified Wagner sleeping-car interior, and the parlor lounge from Dr. Webb’s private car, the Ellesmere. Encircling the base is a train pulled by an engine labeled Ne-Ha-Se-Ne, the name of Dr. Webb’s 200,000-acre private park in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, the Ellesmere, and a tender identified as “Adirondack and St. Lawrence,” the railway line that Dr. Webb built in the region. The trophy’s handles feature winged wheels, the symbol of the Wagner Company.

Unidentified maker (Massachusetts)

Hadley Chest, 1700 25

Oak and pine, 44 7/8 x 45 1/2 x 20 3/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from John Kenneth Byard, 1957, 3.4 35

With its distinctive mannerist-inspired tulip-and-oak-leaf carved façade the Hadley Chest is part of a group of 200 related surviving examples, which were made by unknown joiners near Hadley, Massachusetts. It prominently displays the initials “MW” for Martha Williams of Hatfield, who married Edward Partridge in 1707. Made as part of her wedding celebrations, household goods with an individual’s maiden initials preserved a woman’s birth name even as she lost it in marriage.

Rob Tarule (Essex, Vermont, b. 1941)

Reproduction Hadley Chest, 2000

Oak, pine, and paint, 45 1/2 x 45 13/16 x 20 1/16 in.

Commissioned by the Museum, 2000

The original Hadley Chest would have been decorated with a lively painted surface that had long since been removed before Mrs. Webb acquired it for Shelburne Museum. To explore, recreate, and present to the public a decorative scheme considered fashionable in early 18th century America, the Museum commissioned an identical reproduction using period tools and construction techniques. Scientific analysis determined that the original surface had been so thoroughly stripped that there was insufficient evidence to suggest a color scheme. Research revealed two related chests in public and private collections with identical joinery that were all made and carved in the same shop using the same template. Visual as well as microscopic examination exposed an elaborate paint scheme that included Prussian blue, deep red, black, and white. This distinctive palette is quite startling compared to the stripped surfaces that most expect to see on furniture from this early time period.

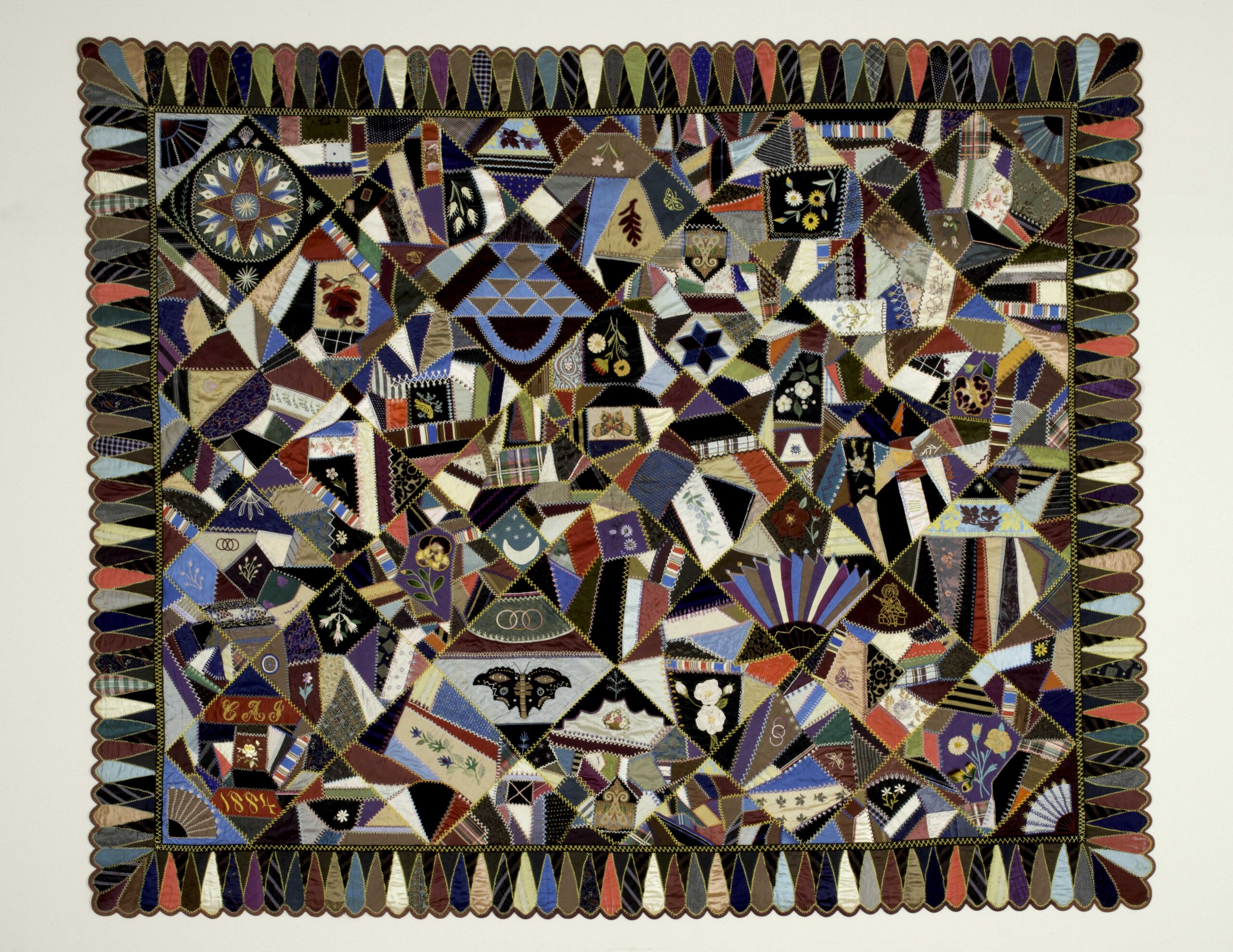

Member of the Eddy Family (New York, New York)

Embroidered and Pieced Crazy Quilt with Flowers and Large Basket, 1884

Cotton and silk, 66 x 72 in.

Gift of M. Lenoir Eddy, 1997 22

Crazy quilts were complex textile scrapbooks of color, texture, and ornament. They were created as artistic statements rather than functional bedcoverings and appeared in the parlor as lap robes, sofa or piano throws, and table covers. Produced during the last quarter of the 19th century in America, the resulting improvisational nature of the pattern was considered odd, bizarre, strange, or “crazy.”<br/><br/>The obsession with Asian aesthetics and Oriental items at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition made Japanese fans a necessity as embellishments on walls, ceilings, and on bedcovers. Rendered in cloth, they punctuate each corner of this quilt inside the unique and decorative teardrop-shaped border. These exotic motifs are combined with embroidered and appliquéd naturalistic flowers, nautical symbols (mariner’s compass stars) and references to Odd Fellow and Masonic themes (three interlocking rings, moon and stars) to create an asymmetrical, one-of-a-kind design.<br/><br/>The resulting rainbow of colors is a fitting summary of Mrs. Webb’s distinctive taste.