Electra Havemeyer Webb collected objects that tickled her fancy. Her signature sense of whimsy can be found throughout Shelburne Museum. Indeed, to visit her museum is to enter a landscape of buildings, gardens, and collections designed to delight while they educate. Certain objects she gathered for their pure ability to amuse or entertain. Humorous genre paintings, a clown automaton, tin flowers, and the trade sign of a dentist named “Comfort” all found a home at Shelburne Museum. The strategies Mrs. Webb employed to display her collection intensified this sense of wonder by creating a surprise and discovery around every corner. From her first folk art purchase of a cigar store figure in the early 20th century to one of her final acquisitions, Andrew Wyeth’s Soaring in 1960, a sense of the unexpected — of joy and playfulness — infused Electra Webb’s collecting.

Whimsy in Music

A playlist by Helen Lyons, host of VPR Classical

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by The Donna and Marvin Schwartz Foundation and the Barnstormers at Shelburne Museum.

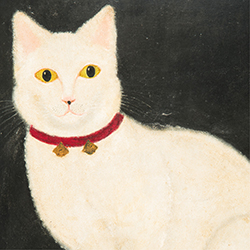

Unidentified artist

Tinkle, 1883

Oil on academy board, 23 1⁄2 x 17 5/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1957-690.16

Perched on an elaborate red cushion and wearing a belled collar, this elegant cat has considerable visual appeal. According to an inscription on the back of the painting, Tinkle, as this cat was called, was “born Febr. 1881,” and was two years and two months old when this portrait was created. Little else is known about Tinkle, its owner, or the artist who painted this work, but the attention given to this portrait suggests that this cat was a valued pet.

Aside from its aesthetic appeal, Tinkle is significant for its role in Shelburne Museum’s evolving collections. Throughout her life, Mrs. Webb preferred collecting three-dimensional objects, but once she had established the Museum, she ventured into paintings in order to create a more comprehensive folk art collection. In 1957 and 1959, she acquired more than a hundred American paintings from the opera singer and art collector Maxim Karolik, including Tinkle.

Unidentified maker

French Clown Magician Automaton, 19th century

Mixed media, 38 ¾ x 20 ½ x 15 ¾ in.

leather, velvet, silk, cotton jersey

Museum purchase, 1961-1.34

Wearing a grin and a slyly-arched eyebrow, this clown magician invites us to a game of illusions. When fully wound, he taps his wand and raises his hat to reveal a chicken, a frog, and other surprises, all of which are stored on a rotating carousel located underneath the game table.

While an automaton can refer to any self-operating mechanism, the term most frequently describes animal or anthropomorphic figures intended for entertainment. Automata designs date to antiquity, but they reached their apex in popularity and diversity during the late 19th century, when industrialization enabled the mass production of the mechanical parts required for these machines. French automata such as this clown magician were especially revered for their high quality, and required the collaboration of clockmakers, sculptors, painters, and other artisans. Though Mrs. Webb primarily collected American objects, she also collected European pieces intended for American markets.

Unidentified maker

Tin Whimsy Bowl of Flowers, 19th century

Tin, iron, and solder, 11 5/8 x 14 ¼ x 13 in.

Museum purchase, 1959-7

Tin whimsies were intended as humorous souvenirs for the 10th wedding anniversary, an event that received significant attention during the 19th century. With illness, childbirth, and accidents curtailing the average lifespan, the 10th wedding anniversary, symbolized through tin, was considered an important marital milestone, and was commemorated through lighthearted celebrations called tin wedding parties. Invitations were usually printed on tin or on paper decorated with tin, and guests would present the couple with gifts of tin. These gifts could be commissioned from a local tinsmith, and were relatively inexpensive to make. Many of these items were exaggerated versions of everyday objects, such as oversized hats or shoes, but they could also be tailored to the couple’s personalities or idiosyncrasies.

Unidentified maker (New England)

Swordsman, 1870-1900

Carved and painted wood and metal, 19 ¼ x 6 1/8 x 12 ¾ in.

1950-293

With his maniacal grin, bulging eyes, and red-tipped swords, this pirate would be a terrifying figure if we encountered him in real life. As a whirligig, however, he becomes an amusement, harmlessly spinning his blades at the slightest nudge of a breeze. The abstracted, geometric nature of his face exemplifies the visual appeal that many folk sculptures held for early 20th-century modern artists and collectors.

Whirligigs have been twirling their way through the American cultural landscape since at least the early 19th century, and were likely introduced by German settlers. Whirligigs appear in a variety of forms, but soldiers, police officers, and other martial figures appear to have been especially popular subjects. The prevalence of such characters suggests that the amusement these toys offered was subversive as well as kinetic in nature, pitting figures of power and authority in futile battle against the wind.

Unidentified maker

Squirrel Cage, ca. 1900

Carved and painted wood, 25 3/16 x 24 x 9 ½ in.

27.FM-53

An elaborate ancestor of the modern hamster wheel, this brightly painted squirrel cage incorporates different kinetic actions into its design. When a squirrel ran in the cylindrical cage, the turning wheel would have powered the mechanisms of the figures operating the saws on top, causing them to rise up and down in a sawing motion. The two boxes on either side of the cage, painted to resemble Georgian townhouses, would have served as nesting areas for the squirrel.

Squirrels were kept as pets in Europe and America in the early 18th and 19th centuries (hamsters were not introduced to the United States until the 20th century). Several elaborate squirrel cages survive, often in the form of miniaturized houses, though Shelburne’s example is unusual in its mechanical complexity.

Unidentified maker (Pennsylvania)

Nine Pins, ca. 1867-1900

Carved and painted wood, 11 ½ x 19 x 4 7/8 in.

Bequest of Electra Havemeyer Webb, acquired from Edith Halpert, The Downtown Gallery, 1941, 1961-1.141

Six smiling faces in medieval headdresses peer out of oversized boots in this unusual ninepins set. A popular precursor" content="to modern-day bowling, ninepins was introduced to America by English and Dutch colonists, and was played in indoor and outdoor settings. While most sets consisted of simply carved pins, more elaborate examples such as this one also survive. Shelburne’s set is missing three pins, possibly the casualties of a heated ninepin match.

While this set might have been created as a game, during the early 20th century it assumed a new life as an esteemed work of folk art sculpture. In 1931, the set was featured in the seminal American folk art exhibition held at the Newark Museum, one of the first shows dedicated exclusively to the subject. In 1937, the ninepins were recorded in watercolor for the Index of American Design, a Depression era federal work relief program dedicated to documenting outstanding examples of American art and design. Playful and sculptural, the set embodies many of the qualities that Mrs. Webb and her contemporaries prized in American folk art.

Attributed to James Hutchinson & Mercedes Hutchinson (New York, active 1925-45)

The 4th of July Picnic Celebration, 1925-45

Wool, cotton, and jute, 45 ½ x 37 in.

Gift of Fred MacMurray, 1973-2.1

A multisensory, intergenerational celebration is commemorated in this festive rug. Mothers push baby carriages, elderly men and women lean on canes, and children light firecrackers. A large red firecracker explodes in the upper left corner, while a picnic replete with cakes, pies, and

other culinary delights, occupies the center. “All Had a Good Time,” is inscribed across the bottom edge, emphasizing the joyous nature of the occasion.

Though not officially recognized by Congress as a federal holiday until 1870, Independence Day has long been celebrated in American culture, with fireworks and other outdoor events becoming common activities. This rug, made sometime around the mid-20th century, exudes a nostalgic quality, showing a high-wheel bicycle, pony cart, and other antiquated equipment. It also glosses over social tensions and ethnic diversity, creating an idealized, homogenous vision of the holiday. It is unlikely that “all had a good time,” but in this piece, happiness is universal.

Unidentified maker

Barber's Chair, ca. 1850-1900

Carved and painted wood and leather, 43 x 25 in.

Gift of J. Watson Webb, Jr., 1953-1181

The Rooster Barber Chair is a playful object that has been made useful. This piece was originally part of a carousel, but was converted into a child’s barber chair at some point in its history. A drawer inserted in the middle of the rooster’s chest would have held the barber’s tools.

Although the Museum acquired this object after Mrs. Webb’s death, its repurposed nature recalls her approach to design and decoration. As a collector, she was always more interested in “the spirit of a period,” rather than total historical accuracy, and was known to convert antiques into useful objects. She turned bandboxes, vases, and other items into lamps, for example, and stripped the paper from bandboxes to decorate the walls at her Westbury, New York, and Shelburne, Vermont, homes.

Unidentified maker

Hobby Goat, ca. 1880

Carved and painted wood, 25 x 7 ¾ x 26 in.

Bequest of Electra Havemeyer Webb, acquired from Helena Penrose, 1961-1.123

Hobbyhorses have a long history dating back to the fourth century B.C. By the 19th century this children’s toy was popular in America, often appearing in portrait painting. This Hobby Goat takes center stage in a 1938 photo taken in Mrs. Webb’s home in Shelburne, where it shares a space with other children’s toys and furniture. The realistic carving and brightly painted saddle and bridle are executed in a manner similar to carousel animals and is probably the work of a professional in the field.

Unidentified makers

Group of Glass Canes, 1875-1925

Glass, between 55 and 29 in.

32.1.4 Group

Shelburne Museum has the largest public collection of free blown glass canes in the United States, numbering 168. During the 19th century, these one-of-a-kind masterpieces were made in every glass house in England, Europe, and the United States from “end of the day” leftover materials to showcase the skill of the anonymous makers. Never intended as walking sticks, these whimsies demonstrate the creativity and craft skills of the artisans who hung them inside the house as decoration, traded them for refreshment at local saloons, and carried them as ceremonial artifacts during Fourth of July and Labor Day parades. Whether solid or hollow with crook, L-shaped or rounded knob handles, and ornamented with applied spirals of molten glass or internal metallic powders, they take advantage of the full spectrum of available colors.

Gustaf Hertzberg (Vermont, ca. 1872-1955)

The Wind, 1900-55

Carved wood, 9 7/8 x 8 1⁄4 x 3 1⁄2 in.

Gift of Russell and Edith Hertzberg, 1986-27.19

These fantastical carvings are the creations of Gustaf Hertzberg. An emigrant from Sweden who lived in Brattleboro, Vermont, Hertzberg spent most of his career working as a painting contractor. In his retirement, he began carving tree burls, a traditional Swedish art form.

According to his children, Hertzberg would study his burls until he discerned a face, animal, or other pattern in the wood, and then used his carving skills to bring the incipient form to fruition, taking care to keep the original shape and idiosyncrasies of the wood intact. Over a period of two decades, Hertzberg would create a diverse array of bizarre creatures and characters, from smiling lambs to fox-shaped ladles.

Unidentified makers

Assortment of Scrimshaw, mid 19th century

Carved and incised ivory, average 6 3/8 x 2 ¾ x 7/8 in.

Gift of George G. Frelinghuysen, 1964-79.6 & 1965-336.12

From the late-18th century until the mid-19th century, whaling was one of the most important industries in the American economy, providing whale oil for fuel, baleen for corsetry, and other materials of everyday life. It was also a tedious undertaking, with voyages lasting several years. To alleviate the boredom that occurred between hunts, many sailors practiced the art of scrimshaw, using leftover bones and baleen to carve tools and make games.

Of the myriad tools that sailors created, jagging wheels, or pie crimpers, are among the most numerous in existence. Often believed to have been carved as gifts, it is debatable whether they were actually used, but they have nonetheless become associated with the longing that sailors experienced for the comforts of home and loved ones left behind. As the four examples illustrated here demonstrate, scrimshaw tools exhibit a remarkable variety of form, ranging from the fanciful to the frankly erotic.