Shelburne Museum’s roots are steeped in the material culture of travel. In 1947, as Electra Havemeyer Webb was laying the foundation for the Museum, she was offered a remarkable collection of historic horse-drawn vehicles collected by the Webb family. Mrs. Webb jumped at the chance, purchasing acreage along Route 7 in Shelburne and setting to work on the construction of the Horseshoe Barn for the storage and display of these objects. Before the end of the year, the carriages were moved from Shelburne Farms to their new home on the Museum grounds where they remain for visitors today.

American Stories: Travel features highlights from the Museum’s holdings that relate to the variety of modes of transportation over land and water that have defined the American experience. Paintings like William Birch’s 1816 Conestoga Wagon on the Pennsylvania Turnpike and Fitz Henry Lane’s 1863 Merchantmen Off Boston Harbor reveal iconic means of transportation that aided European settlers during the 18th and 19th centuries as they headed inland from the Atlantic Coast. These lumbering vessels were soon outmoded by new technologies like trains and steamships that allowed Americans—as well as their wares—to more efficiently navigate great distances. Decked out with fine upholstery and elegant aesthetic finishes, Concord coaches and fancy cutters invited travelers to see the landscape in comfort and style on a more personal scale. Together, these objects chart shifts in consumer preferences and industrial technologies that continue to shape the American experience today.

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by The Donna and Marvin Schwartz Foundation and the Barnstormers at Shelburne Museum.

American Locomotive Company (Schenectady, New York, 1901–69)

Locomotive 220, 1915

Steel

Gift of Central Vermont Railroad, 1955-716

The Locomotive 220 was built in 1915 by the American Locomotive Company of Schenectady, New York. It was the last coal-burning, steel ten-wheeler used on the Central Vermont Railroad. The 220 pulled freight and carried passengers, and became known as “The Locomotive of the Presidents” because of its use on special trains carrying Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. The Central Vermont Railroad donated the Locomotive 220 to the Museum in 1955.

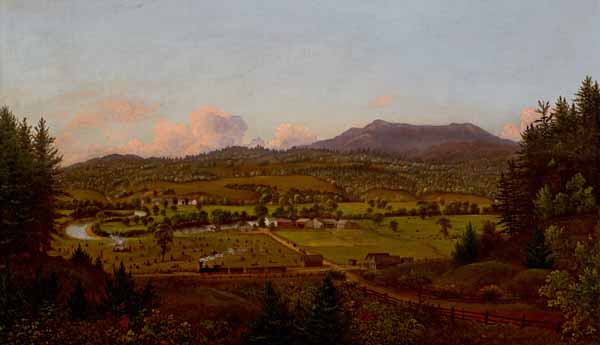

Charles Louis Heyde (American, 1822–92)

Steam Train in North Williston, Vermont, ca 1856

Oil on canvas, 20 9/16 x 35 3/16 in.

Gift of Edith Hopkins Walker, 1959-49.1

Although little is known of Heyde’s early life, it is recorded that he traveled by train from Brooklyn to North Dorset, Vermont, in August 1852. Like many of his contemporaries, the artist sought inspiration from the American landscape. Rather than heading to the upper banks of the Hudson or New Hampshire’s White Mountains, which were more common destinations for his peers, Heyde eventually settled in Burlington and chose to paint Vermont’s Green Mountains. The majority of the artist’s paintings include area landmarks that remain identifiable today: Mount Mansfield, Camel’s Hump, Lake Champlain, Shelburne Point, the Winooski River, and Otter Creek. Painted not long after Heyde’s arrival, Steam Train in North Williston, Vermont includes Mount Mansfield’s distinctive silhouette set against a cloud-dappled sky. With the arrival of the Vermont Central Railway in 1850, North Williston became home to grist mills, a poultry warehouse, a cheese factory, creameries, and New England’s first cold storage plant, enabling the freezing and exportation of meat and poultry from Vermont to other cities in the Northeast.

Thomas Birch (American, b. England, 1779–1851)

Conestoga Wagon on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, 1816

Oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 28 ½ in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Harry Shaw Newman, The Old Print Shop, 1961-1.64

Born in England, Thomas Birch arrived in Philadelphia in the 1790s to assist his father William with the preparation of a 29-plate collection of engravings they titled Birch’s Views of Philadelphia. First published in 1800, Birch’s Views were enthusiastically received and inspired Thomas to continue to paint landscapes and marine paintings, many of which were translated into affordable prints for American consumers. In this painting, Birch has depicted a Conestoga wagon—the primary cargo vehicle over the Appalachian Mountains until the development of the railroad—heading west on the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike. Credited as the first long-distance paved road built in the United States and used starting in 1795, this thoroughfare would have been familiar to the artist as a modern marvel of engineering.

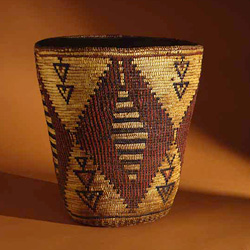

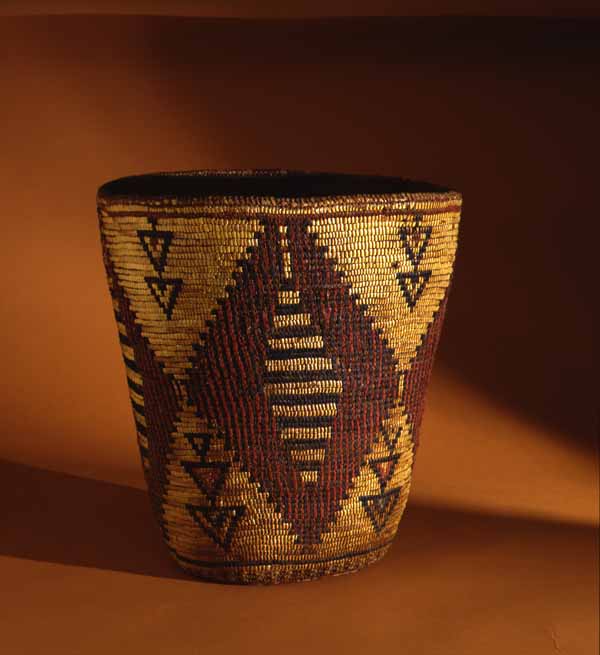

Possibly Salish (Flathead) Nation (North America)

Carrying Basket, date unknown

Reed, grass, and bark, 16 x 14 ½ in.

Gift of J. Watson Webb, Jr., 1973 13

This coiled basket is thought to have been created by a member of the Salish nation, a network of indigenous communities connected by a common linguistic tradition living around the Columbia and Fraser River Basins in the Pacific Northwest. These communities employ a variety of basket forms for seasonal uses, ranging from round bags for spring root gathering, to flat bags that can be tied to horses for travel during the summer months, to baskets convenient for collecting berries in the fall. The decorative features of these vessels have been steeped in hundreds of years of intercultural trade, first with other indigenous peoples and later with Anglo-American traders.

This basket was part of Louis Comfort Tiffany's collection of indigenous material culture displayed at Laurelton Hall, his country estate in Long Island, New York. Art historian Elizabeth Hutchinson has noted that while these kinds of objects are often perceived as souvenirs of American travel, urban collectors like Tiffany might have obtained objects via mail-order catalogues, specialty dealers of indigenous artifacts, or even the numerous “Indian Stores” around Broadway and 23rd Street in New York City during the early 20th century.

Ledoux & Company (Montreal, Canada, 1852–1920)

Fancy Cutter, ca. 1885

Wood, metal, leather, wool, horsehair, cotton, and feathers, 60 ½ x 47 x 69 in.

Gift of the Webb Family in memory of Dr. and Mrs. William Seward Webb, 1947-18.25

When snowy weather set in during the late fall and winter, 19th-century residents of colder regions like northern New England and Canada transitioned from the use of wheeled buggies to sleighs and cutters on runners that could glide smoothly across deep snow. As winter vehicle design became more functional manufacturers like B. Ledoux & Company began to lavish greater care on the woodwork and ironwork of their vehicles. Fashion trends demanded more elegance and refinement, delicate lines and softer tones, and the cutter became a thing of beauty—not unlike current trends in customizing automobiles. By 1885 Canadian maker Ledoux was producing sleighs like this dark red fancy cutter with green broadcloth interior.

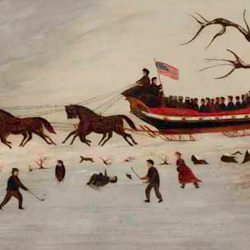

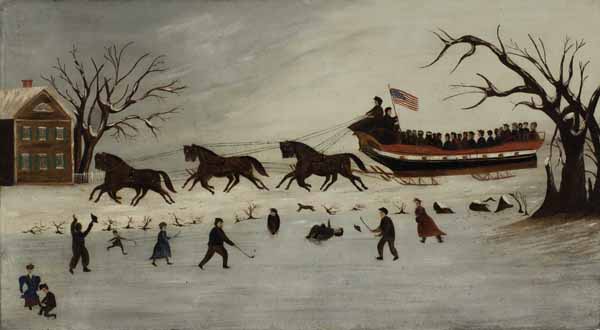

Unidentified artist

Suffragettes Taking a Sleigh Ride on the Constitution, 1870–90

Oil on canvas, 20 ¼ x 36 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1957-690.12

These women are likely traveling via sleigh to a rally in support of women’s suffrage. Suffragists were the target of ridicule in prints and cartoons, and the unidentified artist behind this picture may have based this painting on one of those images. Despite the patriotic symbolism of the eagle and the sleigh called the Constitution, the women pass unnoticed through an everyday scene. Only the African-American man in the lower left corner of the composition acknowledges them.

The campaign for women to gain the right to vote began with the Seneca Falls Convention in July 1848. In 1866, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed the Equal Rights Association to support suffrage for all, and three years later in 1869 formed the National Women Suffrage Association. The Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the right to vote, was not passed until August 26, 1920. In 1923, the National Women's Party proposed an amendment to the Constitution that prohibited all discrimination on the basis of gender. The so-called Equal Rights Amendment has not yet been ratified.

Abbot Downing Company (Concord, New Hampshire, 1827–47)

Concord Coach, ca. 1828

Wood, metal, leather, canvas, velvet, and lace brocade, 98 x 80 x 159 in.

Gift of Mrs. Francis R. Appleton, Jr., 1974-123

Producing more than 1,500 coaches, filling orders from South America, Australia, and Africa and every state and territory in the Union, the Abbot-Downing Company manufactured the equivalent of the Greyhound buses of their day. Lewis Downing opened a wheelwright shop in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1813. He later produced his own wagons and introduced improvements such as the sidebar spring which he, unfortunately, neglected to patent. When he had difficulty carrying out some of his innovative design ideas, Downing advertised for a master coach builder, and J. Stephens Abbot of Salem, Massachusetts, responded. Together, Abbot and Downing produced the Concord coach, which revolutionized coach design by setting the body on two wide leather thoroughbraces running front to rear. This unique suspension system gave the coach a gentle, swaying motion, which was a great improvement over conventional steel suspension.

Enoch Wood Perry (American, 1831–1915)

The Pemigewasset Coach, 1899

Oil on canvas, 42 5/8 x 66 5/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Harry Shaw Newman, The Old Print Shop, 1961-1.62

Enoch Wood Perry received wide acclaim for his paintings of rural New England life that blended nostalgia and current events. In The Pemigewasset Coach, a composition the artist reworked several times and even produced as a lithograph, viewers are encouraged to conjure and celebrate a way of American life that had all but disappeared by the close of the 19-th century. The painting’s title derives from the name of the horse-drawn stagecoach that carried New Hampshire summer travelers between Concord and the Pemigewasset House in Plymouth. By the 1890s, most travelers would have journeyed by train, and coaches like this one were an anachronistic nod to a simpler, less industrialized past. Populations in small communities like Concord and Plymouth were rapidly dwindling as young people relocated to urban centers in search of factory jobs. Paintings like this one appealed to consumers in large cities who yearned for the past, whether real or imagined.

Fitz Henry Lane (American, 1804–65)

Merchantmen Off Boston Harbor, 1863

Oil on canvas, 24 ¼ x 39 3/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1957-690.49

In the 1850s and 60s, Fitz Henry Lane traveled along the New England coastline painting harbors from Boston to Maine. Many of Lane’s marine paintings are paeans to evolving American mercantile culture, ingenuity, and sailing designs. The pale light that bathes this composition hints at early morning, a busy time in the harbor. Accordingly, a small but mighty harbor tug at the left side of the canvas ushers a lumber brig to a wharf for unloading. Beyond the tug is a small coasting schooner, another working boat, likely headed to another pier to pick up cargo or for unloading or maintenance. Three sizable merchant ships, with loose square sails, sit at anchor. Close examination of the picture also reveals two side-wheel steamers, meant to transport people and goods to and from coastal ports.

James Bard (American, 1815–97)

Paddle Steamboat Kaaterskill, 1882

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on wove paper, 27 ½ x 51 in.

Museum purchase, 1951, acquired from Harry Shaw Newman, The Old Print Shop, 1951-391.35

Working from his residence in lower Manhattan, the artist James Bard met the demand for painted ship portraits within a burgeoning steamboat industry. Bard completed nearly 4,000 commissions for engine builders, ship captains, merchants, and other maritime entrepreneurs. Those canvases were created to be hung in commercial rather than domestic settings and were valued for their highly accurate representations and as celebrations of beauty, speed, national achievement, and successful business acumen.

It is no surprise, then, that Bard chose the Kaaterskill for a subject. Built for the Catskill Evening Line by Van Loon Magee in Athens, New York, the ship was the pride of the line and the flagship of the fleet. Steaming down the Hudson for her maiden voyage in August 1882—the same year that this watercolor is dated—this speedy, luxuriously furnished vessel’s 150 staterooms and 73 cabins could accommodate up to 300 passengers with additional freight.

Champlain Transportation Company (Burlington, Vermont, est. 1826)

Ticonderoga, 1905–06

Steel, wood, and paint, 57 x 220 ft.

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb, 1951-395

The Ticonderoga—affectionately known as the “Ti”—was built in 1906 at the Shelburne Shipyard on Lake Champlain. Measuring 220 feet in length and 59 feet in beam, the ship is a side-paddlewheel passenger and freight steamer with a vertical beam engine. Its steam-powered engine, built by the Fletcher Engine Company of Hoboken, New Jersey, could travel 17 miles per hour.

The Ticonderoga originally operated on a north-south route, carrying travelers and freight from New York City to St. Albans, Vermont, as well as an east-west route from Burlington, Vermont, to Port Kent, New York. When steamboats became obsolete and use of the Ticonderoga as an excursion boat became less popular, Ralph Nading Hill (1917–1987), a Vermont historian and preservationist, persuaded Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb to purchase and save the vessel. Shelburne Museum briefly maintained operation of the Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain, but in 1954 the decision was made to move it to the Museum grounds—two miles over land—during the winter of 1954 to 1955.

United States Lighthouse Service (American, 1789–1939)

Designed by Albert R. Dow (Vermont), Constructed by Luther Whitney (Vermont)

Colchester Reef Lighthouse, 1871

Wood, stone, and paint

Museum purchase, 1952-1248

Lake Champlain was a critical shipping route for Vermont’s thriving lumber industry during the mid-19th century. Located just northwest of Burlington, Colchester Reef, Colchester Shoals, and Hogback Reef—collectively known as the “Middle Reef Bunch”—were especially hazardous for marine traffic. Considering the negative impact these impediments might have on regional commerce, the United States Lighthouse Service commissioned the construction of a lighthouse at Porter’s Point, Colchester, in 1869. Burlington native and University of Vermont graduate Albert R. Dow won the contest, and the lighthouse was erected in 1871. Operational for more than 60 years, the structure was home to 11 successive keepers and their families.

In 1933 the Lighthouse Service decommissioned the structure: automatic, electric technologies had rendered the antiquated, hand-operated beacon system obsolete. In 1952 the derelict structure was auctioned to Winooski residents Paul and Lorraine Bessette who, in turn, sold the building to Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb.