Electra Havemeyer Webb possessed a keen sense of scale, collecting objects large, small, and in prodigious quantity. Her aspirational spirit, witnessed by such heroic feats as moving historic houses, a covered bridge, a lighthouse, and the steamboat Ticonderoga to create Shelburne Museum in the decade after World War II, balanced deeply held interests in the details and nuance of collecting. Mrs. Webb stands out for the way she composed a series of experimental and experiential environments in which to display and interpret one of the premier collections of art, Americana, and design in the United States. She populated her Vermont museum with oversized trade signs and diminutive salesman samples, model trains and a train, nineteenth century ship’s paintings and a ship. Simultaneously intimate and grand, her vision has delighted visitors for over 65 years.

Scale in Music

A playlist by musician Ryan Miller, lead singer and guitarist for Guster

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by The Donna and Marvin Schwartz Foundation and the Barnstormers at Shelburne Museum.

Unidentified maker

Padlock Trade Sign for Hardware Store, 1867-1900

Wood, metal, and paint, 38 x 24 in.

Museum purchase, 1953, acquired from Edith Halpert, The Downtown Gallery, 1961-1.180

Trade signs advertised goods and services in an era when literacy was not a foregone conclusion. For an optometrist in an Atlantic seaport, or a dentist in a city with a large immigrant population, such symbols solved a fundamental problem of communication, occasionally in humorous fashion. Over time these common objects became collected for their aesthetic merit. Trade signs have been favorites at Shelburne Museum for decades and several have toured the country as icons of folk art. The tromp l’oeil padlock, for example, was exhibited at The Downtown Gallery in 1963. This famous New York venue, brainchild of Edith Gregor Halpert (1900-1970), introduced many to the world of American folk art.

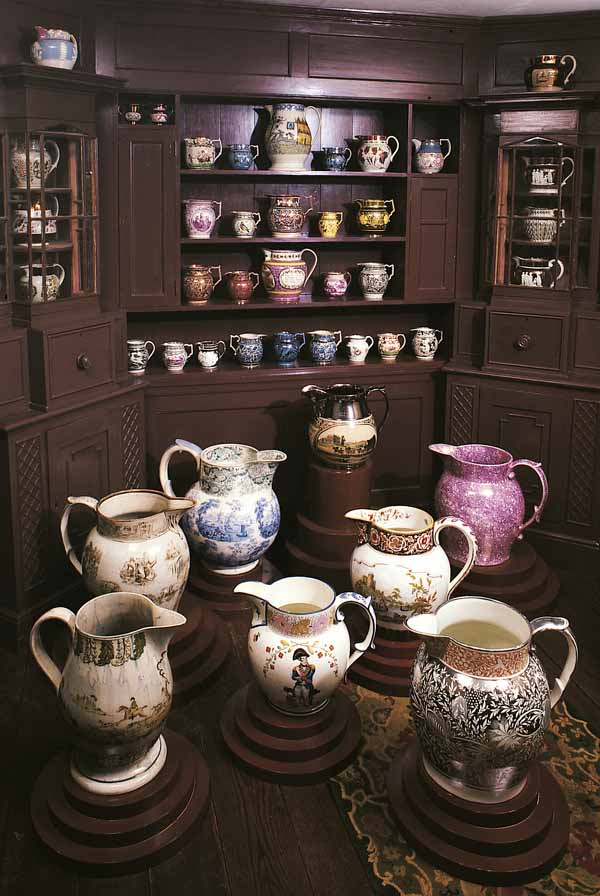

John Potter (Staffordshire, England) & Unidentified maker

Mammoth Jug & Lusterware Country House Transfer Pitcher, about 1810

Ceramic 1961-1.21 & 31.21-6

Various makers (Staffordshire, England)

Assortment of Jugs & Pitchers, 1815-30

Earthenware, between 4 3/4 x 3 in. and 24 1/4 x 29 x 14 3/4 in.

31.2-1 &31.21 Groups

Various makers (Staffordshire, England)

Assortment of Jugs & Pitchers, 1815-30

Earthenware, between 4 3/4 x 3 in. and 24 1/4 x 29 x 14 3/4 in.

31.2-1 & 31.21 Groups

Oversized pitchers and jugs were manufactured by the individual firms of Staffordshire and other storied ceramic producing English cities for commemorative purposes, to advertise their wares, and to demonstrate expertise. In the early decades of the nineteenth century such oversized vessels would be placed in shop windows of fashionable emporiums in England and America to drum up trade in the burgeoning consumer culture of the Atlantic rim economy. In Mrs.Webb’s day, these rare forms became prized by collectors for their scale and rarity.

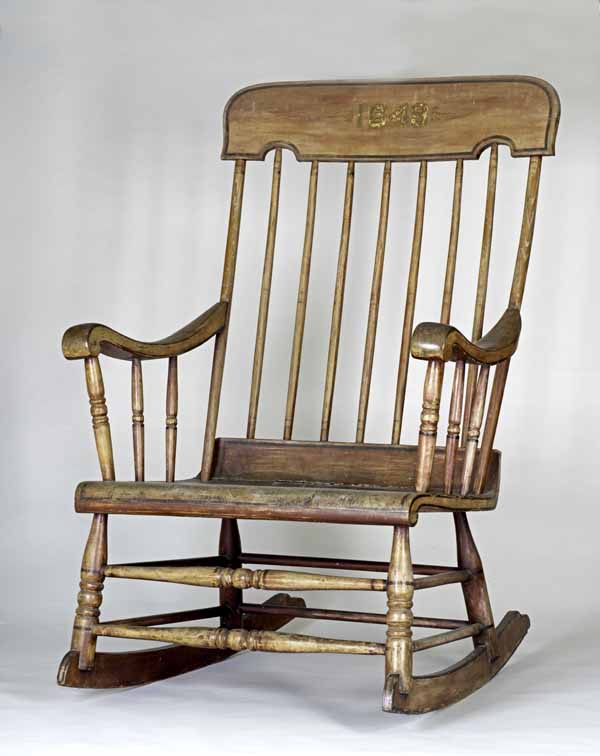

Unidentified maker (Morrisville, Vermont)

Boston Rocker, 1849

Wood and paint, 78 x 48 x 36 in.

Museum purchase, 1957-127

Unidentified maker

Zasu Pitts and Electra Havemeyer Webb outside Stagecoach Inn, 1958

Gelatin silver print, 8 x 10 in.

PS1.10-Pitts.1

Electra Havemeyer Webb purchased this heroic-sized chair from a Vermont antiques dealer in 1957. It originally graced a glazed cupola on top of a chair factory in Morrisville, Vermont, and served to advertise the firm’s wares as a trade sign in the last half of the nineteenth century. The date may represent the founding of the company. The chair proved to be a favorite of Mrs. Webb’s and she frequently posed family and friends, including the actress and comedienne Zasu Pitts (1894-1963), in the oversized seat for a humorous photograph.

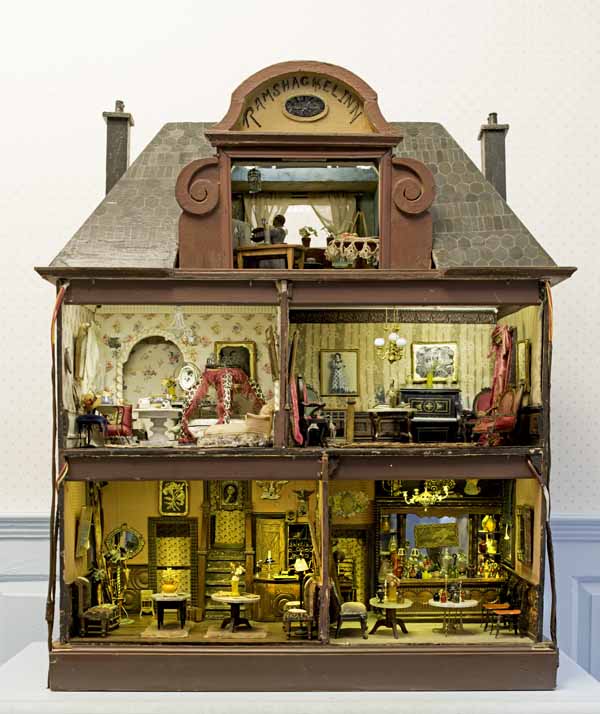

Duncan Munro (American, 1904-77) & Electra Havemeyer Webb (American, 1888-1960)

Ramshackle Inn Doll's House, date unknown

Mixed media, 37 ½ x 31 5/16 x 16 3/8 in.

Gift of Zasu Pitts, 30.1-5

In the late 1940s the actress and comedienne Zasu Pitts (1894-1963) presented Electra Havemeyer Webb with a commercially manufactured turn-of-the-century French dollhouse for her new museum. Early Shelburne Museum staff members then altered the building to honor Pitts’ role in the 1944 Broadway play Ramshackle Inn by extending the roof and decorating the dollhouse to mimic the stage set of the original comedy about a haunted Massachusetts hotel. In this way, the dollhouse embodies both Webb’s interest in miniature environments and her desire to make Shelburne Museum a whimsical experience for visitors.

Unidentified maker (Massachusetts)

Oversize Slat Canada Goose Decoy, date unknown

Wood and paint, 37 x 18 ½ x 62 ½ in.

Gift of Sterling D. Emerson, 1971-13

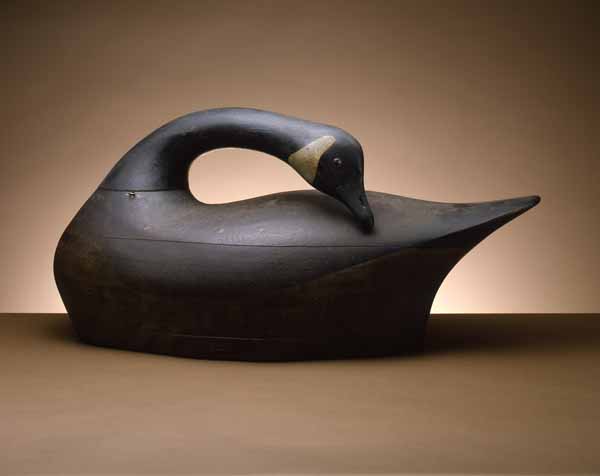

Captain Charles Christopher Osgood (Salem, Massachusetts, 1820-86)

Canada Goose Sleeper Decoy, ca. 1849

Wood, paint, metal, and leather, 11 1⁄2 x 10 1⁄2 x 24 1⁄4 in.

Gift of Mrs. P.H.B. Frelinghuysen, 1953-301.4

Oversized geese are called “quarter mile” decoys for their ability to be seen from that great distance. Slat geese are often attributed to the shop of legendary carver Joseph Lincoln (1859- 1938) of Accord, Massachusetts, though this example is simpler than identified examples by Lincoln. Constructed of wooden slats in the manner of a small boat, such decoys found great favor on Cape Cod in the decades that bracketed the turn of the century. Early collectors found the aesthetics of the form pleasing and slat geese became an icon of American folk art by the mid-twentieth century.

A. Elmer Crowell (American, 1862-1952)

Miniature Blue Jay and Stump Carving, ca. 1939

Wood, paint, and metal, 3 5/8 x 1 7/8 x 2 3/8 in.

Gift of Mrs. Stuart Crocker, in memory of her husband, 1966-232.87

A. Elmer Crowell (American, 1862-1952)

Miniature Wood Duck Drake Bird Carving, ca. 1939

Wood, paint, and metal, 3 3/16 x 2 1/8 x 4 1/8 in.

Gift of Mrs. Herman A. Myers, 1977-38.7

A. Elmer Crowell (American, 1862-1952)

Miniature Canada Goose Bird Carving, ca. 1939

Wood, paint, and metal, 3 15/16 x 2 3/8 x 5 1⁄2 in.

Gift of Mrs. Herman A. Myers, 1977-38.19

Elmer Crowell is considered the “father of American bird carving.” He came of age on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in an era when “market gunning” or commercial hunting of shore birds filled the larders of middle-class American homes. By the late nineteenth century, sportsmen discovered duck hunting and required effective decoys thereby creating a cottage industry of carvers. Crowell’s miniatures evolved in the early years of the twentieth century as collectors became interested in his work. By 1914, he was filling individual orders of up to sixty species creating a silent aviary for his patrons.

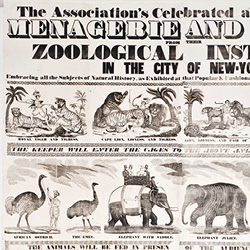

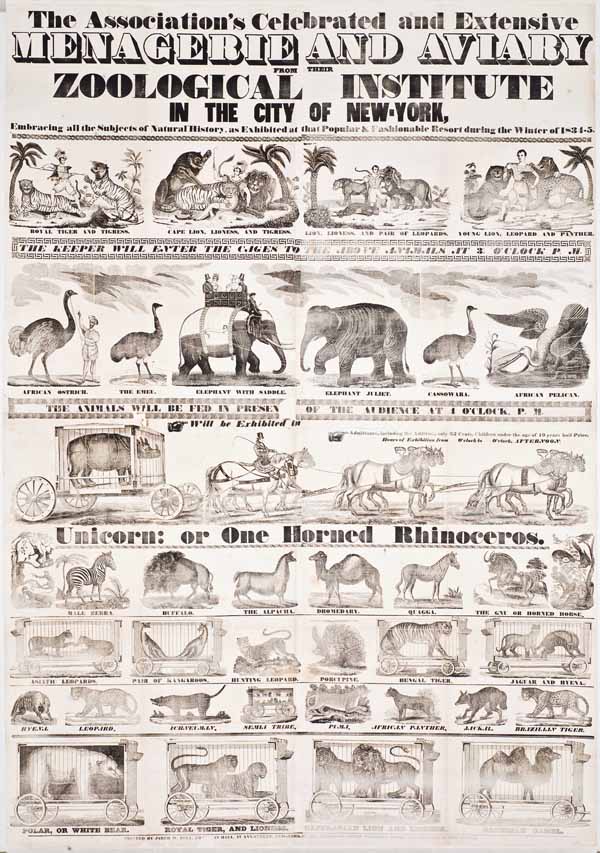

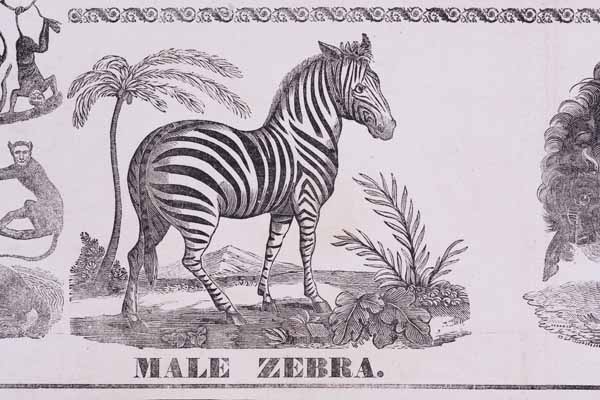

Jared W. Bell (New York, New York)

The Association’s Celebrated and Extensive Menagerie and Aviary / Zoological Institute, 1835

Wood‑cut, engraving, and letterpress print on paper, 111 ¼ x 77 ¾ in.

Gift of Harry T. Peters, Jr., Natalie Peters, and Natalie Webster, 1959‑67.78

Measuring 6 ½ feet wide by 9 feet tall, this poster was produced using more than three dozen hand-carved wood" content="patterns, several of which were signed by the individual artists. As advertised at the bottom of the poster, it was printed—in four parts—by Jared Bell on a steam-powered Napier Cylinder Press, which quickly and efficiently reproduced the large-scale advertisement tens of thousands of times. In spite of the high volume in which the poster was printed, only two extant examples are known to exist. This particular poster is considered rarer still because the spaces to the right of the manicules, or “printer’s fists,” where the location, date, and time of the performances were to be filled in by the billposter were left blank, meaning it was never used.

Roy Arnold (Hartwick, Vermont, 1892-1976)

Two Hemisphere Band Wagon, Arnold Circus Parade, 1925-55

Carved and painted wood Museum purchase, 1959-259.54.64

Unidentified maker

Roy Arnold with Arnold Circus Parade, before 1976

Ink on paper

1959-259

Measuring 6 ½ feet wide by 9 feet tall, this poster was produced using more than three dozen hand-carved wood" content="patterns, several of which were signed by the individual artists. As advertised at the bottom of the poster, it was printed—in four parts—by Jared Bell on a steam-powered Napier Cylinder Press, which quickly and efficiently reproduced the large-scale advertisement tens of thousands of times. In spite of the high volume in which the poster was printed, only two extant examples are known to exist. This particular poster is considered rarer still because the spaces to the right of the manicules, or “printer’s fists,” where the location, date, and time of the performances were to be filled in by the billposter were left blank, meaning it was never used.

Alonzo A. Pratt, Sr. (North Scituate, Massachusetts)

Pratt's Express Children's Wagon, 1890

Wood, paint, and metal, 19 ½ x 27 ½ x 38 in.

Gift of Mrs. Carleton Nowell and Orison S. Pratt, 1969-74

The need to house the family carriage collection is often cited as the genesis of Shelburne Museum and this small child-size wagon demonstrates how Mrs. Webb animated her museum by exhibiting like objects of varying scale. Made by Alonzo A Pratt Sr., a blacksmith from Scituate, Massachusetts, this small pull toy is an exact replica of a full-size buckboard wagon, designed to entertain his son Alonzo Jr. The senior Pratt not only constructed and painted the wagon’s wood body and wheels, but also hand forged the vehicle’s undercarriage, axels, and wheel rims.

Probably Marklin & Co. (Germany)

Toy Steamship ‘Brooklyn’, ca. 1904

Polychromed tin and iron, 12 5/16 x 9 3/8 x 30 3/8 in.

Museum purchase, 1952, 22.5-1

Unidentified makers

Assortment of Toy Boats, ca. 1904

Polychromed tin and iron, between 2 x 2 x 4 9/16 in. and 12 5/16 x 9 3/8 x 30 3/8 in.

Museum purchase, 1952, 22.5-1 Group

Electra Havemeyer Webb’s playful sense of scale drew her to collect thematically. Not only did she rescue the steamboat Ticonderoga by moving it to Shelburne Museum in the winter of 1955, but she gathered paintings and toys that evoked the halcyon days of steam. This tinplate boat, made by Marklin and Company of Germany, employs a clock works to power the vessel. Founded in 1859 to manufacture dollhouse furniture, Marklin is best known for producing high quality toy trains and for creating the popular standard “HO” and “O” gauges in use throughout the twentieth century. Marklin boats were expensive toys in their day and soon became prized by collectors.

James Bard (American, 1815-97)

Paddle Steamboat Metamora, 1859

Oil on canvas, 34 1/8 x 54 1/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Harry Shaw Newman, The Old Print Shop, 1951-391.40

James Bard, though all but forgotten at the time of his death in 1897, produced an extraordinary catalogue of steamships paintings in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Born in New York City to British parents, James and his brother John lived in an era of booming ship construction and made their living by painting commissioned portraits of commercial vessels. By some estimates they produced close to three thousand paintings and drawings in the course of their careers. The Metamora was built in New York City in 1846 and made daily trips to Albany. Cheerful symbols of progress, Bard paintings found great favor with collectors of American folk art in the twentieth centur —including Electra Havemeyer Webb who, at one time, owned seven examples of their work.

Champlain Transportation Company (Burlington, Vermont, est. 1826)

Ticonderoga, 1905-06

Steel, wood, and paint, 57 x 220 ft.

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb, 1951-395

On April 6, 1955, Mrs. Webb presided over the installation of the largest object in Shelburne Museum’s collection. That day, the 220-foot long Ticonderoga, the last functioning sidewheel steamboat in America, concluded its 9,250 foot overland journey from Shelburne Bay to its permanent dry-dock in the middle of the Museum’s campus. In its heyday, the massive boat ferried both passengers and cargo up and down nearby Lake Champlain, displacing a 982 tons of water not to mention the additional weight of travelers, crew, and freight.