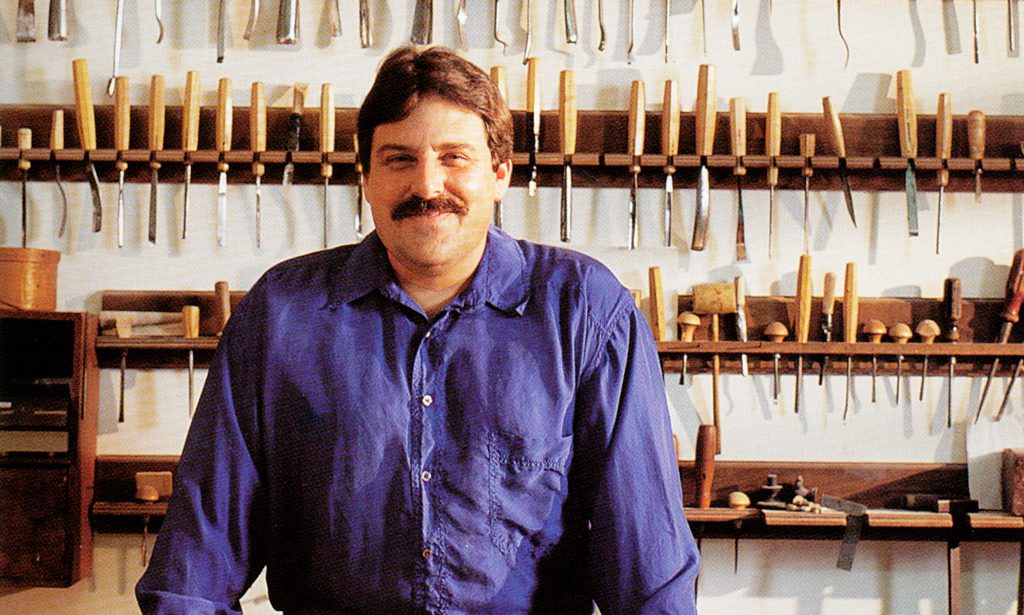

Unknown photographer

Stephen Huneck (American, 1948-2010), n.d.

Courtesy of Friends of Dog Mountain

A self-taught woodcarver and printmaker, Stephen Huneck (1948–2010) developed a style distinctly his own. Over four decades working in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, Huneck moved fluidly among artistic media, experimenting in woodworking, painting, printmaking, children’s books, and more. Central to the artist’s practice was his keen sense of humor, an interest in transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary, and, frequently, the inclusion of dogs. While canines and their adoring humans appear regularly throughout Huneck’s oeuvre, he also included a menagerie of other creatures in his art, including cats, birds, fish, and farm animals.

Utilizing simple forms, saturated colors, bold textures, and, at times, the written word, Huneck’s multimedia artwork reveals how animals humanize people. Huneck was inspired by the world around him, but he also worked “from within,” as he put it, drawing upon his strong bond with his dogs. Pet Friendly: The Art of Stephen Huneck explores the artist’s innate ability to capture this complex, centuries-long relationship.

This online exhibition features a selection of Huneck’s woodcut prints, all of which are recent acquisitions to the Museum’s permanent collection and generously donated from the Friends of Dog Mountain. These prints, along with additional sculptural artwork on loan from Friends of Dog Mountain, will be on view in an exhibition of the same title at the Museum’s Pleissner Gallery from May 13 to October 22, 2023.

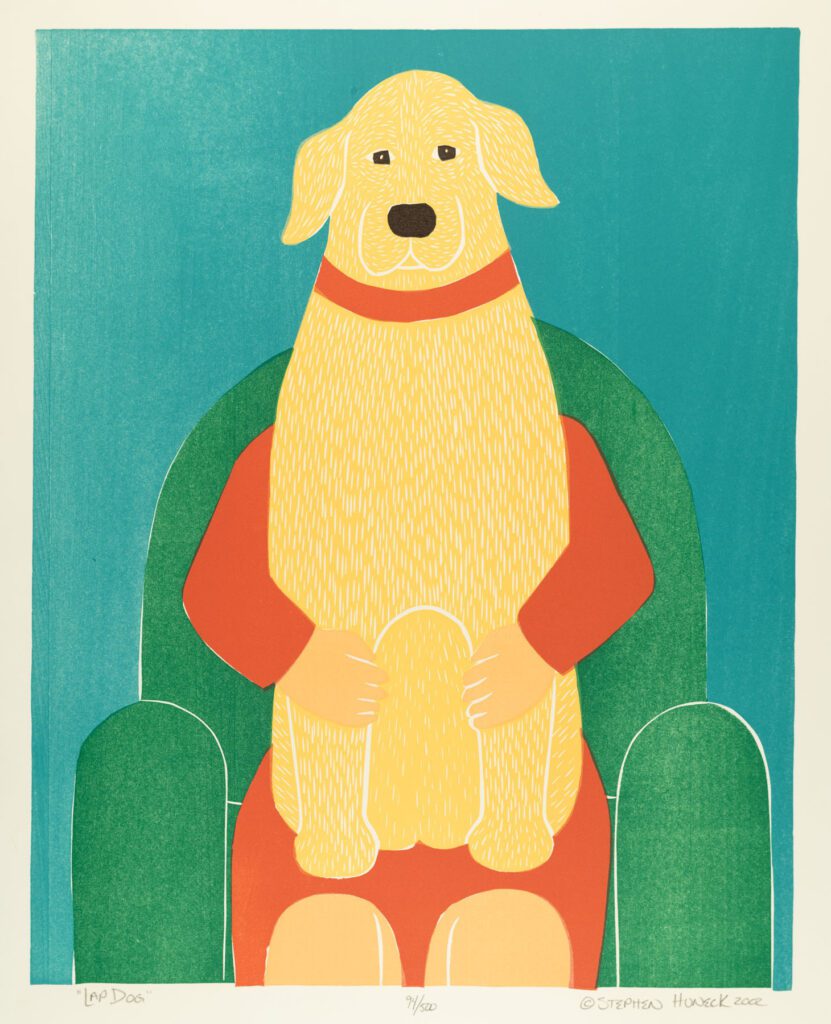

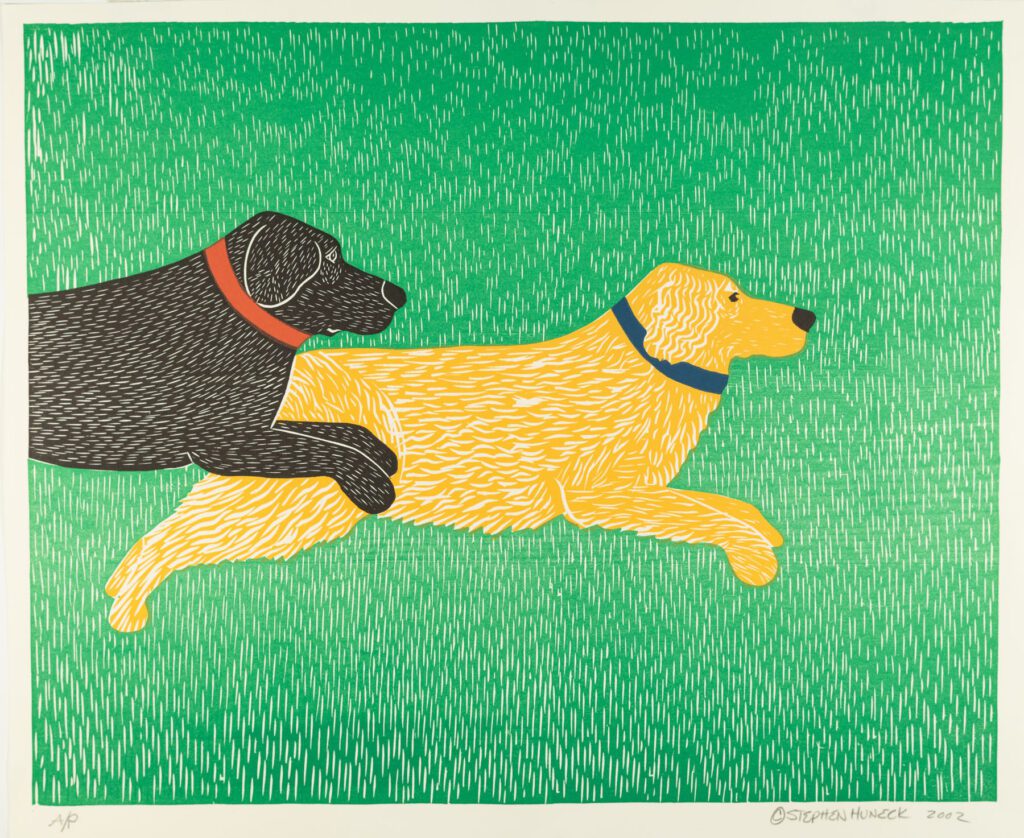

Lap Dog, 2002

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.14

Throughout Huneck’s life, he experienced poignant visions that shaped his artistic career. In 1994, he suffered a debilitating fall that developed into acute respiratory distress syndrome and left him in a two-month long coma. During this time, Huneck had a dream about a sculpture so alive it was “pulsating with energy.” This vision led him to embrace a new medium of woodcut printmaking.

His first prints were dynamic, bold, and colorful, just like his sculptures. He compiled this series into his first children’s book, My Dog’s Brain, which explores the simple yet infinite love dogs have for their humans and for life.

Both Lap Dog and Dog Toys [Good Boy] (on view nearby) were included in this publication. The artist’s cherished black Labrador retriever, Sally, is featured in all of the book’s illustrations, representing what Huneck saw as “a sort of canine Everyman,” but in these two prints, yellow and chocolate Labradors have replaced Sally. By simply changing the dogs’ colors during the printing process, Huneck was able to expand the series and represent a multitude of different Labradors.

Dog Toys [Good Boy], 1997

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.6

Greetings, ca. 1994

Graphite on vellum

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.42

Huneck explained how he began his woodcut prints by first drawing “the design of the future print in crayon, [and] laying out the prospective shapes and colors.” Greetings, a pencil drawing on transparent vellum, is an example of this first, forgiving step, which allowed the artist to make small changes.

Hello Molly, Hello Sally, 2002

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.17

Once content with the composition, Huneck carved one block of wood for each color in its appropriate shape. After inking a block with its respective color, he would hand rub acid-free archival paper on top of the block, and then repeat this process for each color block.

Similar in design to its initial sketch, the woodcut print Hello Molly, Hello Sally demonstrates how the printmaking process enriches the final work. In the print, the grain of the wood, textured markings from the chisel, and saturated pools of inked color enhance the original design.

It Wouldn’t Be Heaven Without Dogs, 2008

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.16

In 1997, Huneck felt compelled to construct a small chapel on his studio and gallery property after, as he explained, “a wild idea just popped into my head.” Utilizing an existing outbuilding’s foundation, the artist built a small building in the style of a 19th-century New England village church, complete with white clapboard siding and a steeple. Decorated with Huneck’s canine art, sculptures, and furniture—including stained-glass windows—this inclusive space is welcome to “all creeds, all breeds, no dogmas allowed.”

Visitors are encouraged to add handwritten letters and photographs of their deceased pets to the chapel’s interior walls, providing a place to mourn their loss while also celebrating the spiritual bond between humans and their pets. Today, the chapel is a pilgrimage site, attracting visitors from across the world to Dog Mountain.

Heaven illustrates Huneck’s belief in an afterlife enriched by reunions with beloved pets. This print was included in the artist’s popular 2002 book, The Dog Chapel, which recounts the artist’s miraculous recovery from a serious injury, which left him in a coma for several months, and a vision that inspired his first series of woodcut prints and, ultimately, the construction of the chapel.

Play, 2002

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.22

Master of the Universe, 1998

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends

of Dog Mountain, 2022-3.20

Lucky Dogs (Eye on the Pie), date unknown

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.19

Huneck had an uncanny ability to breathe vitality into his art through his dynamic carving technique. “I use carving to create rhythm,” Huneck said. “Crosshatching does it on sculpture or a print. A pediment, a column, or an urn endows a building with energy. On furniture, it’s the way the drawers are positioned or the knobs are placed, the way a finial is attached. Moldings direct the eye and complete a design. A trailing-vine border is a wonderful way to move energy around a piece. If the eye is moving, energy is traveling like an electrical charge. I’ve learned that you have to release that energy, or the piece is constipated.”

Paleontologist, 2007

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.37

Throat Exam, 2003

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.27

“Texture is very important to me,” Huneck reflected. “I use it in all my carving, but it is a very difficult thing to do in printmaking. I really needed all those years as a sculptor to master the medium.” When he was beginning to experiment with printmaking, he approached the new medium as a carver. “It is much easier to carve with a v-chisel than to sculpt. You are not taking away a lot of wood. So, I sat down and started doing these drawings. Ideas were popping into my head, ideas that were realized as prints. A whole new door had opened in my mind.”

Vermont Ski Patrol, 2004

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022-3.38

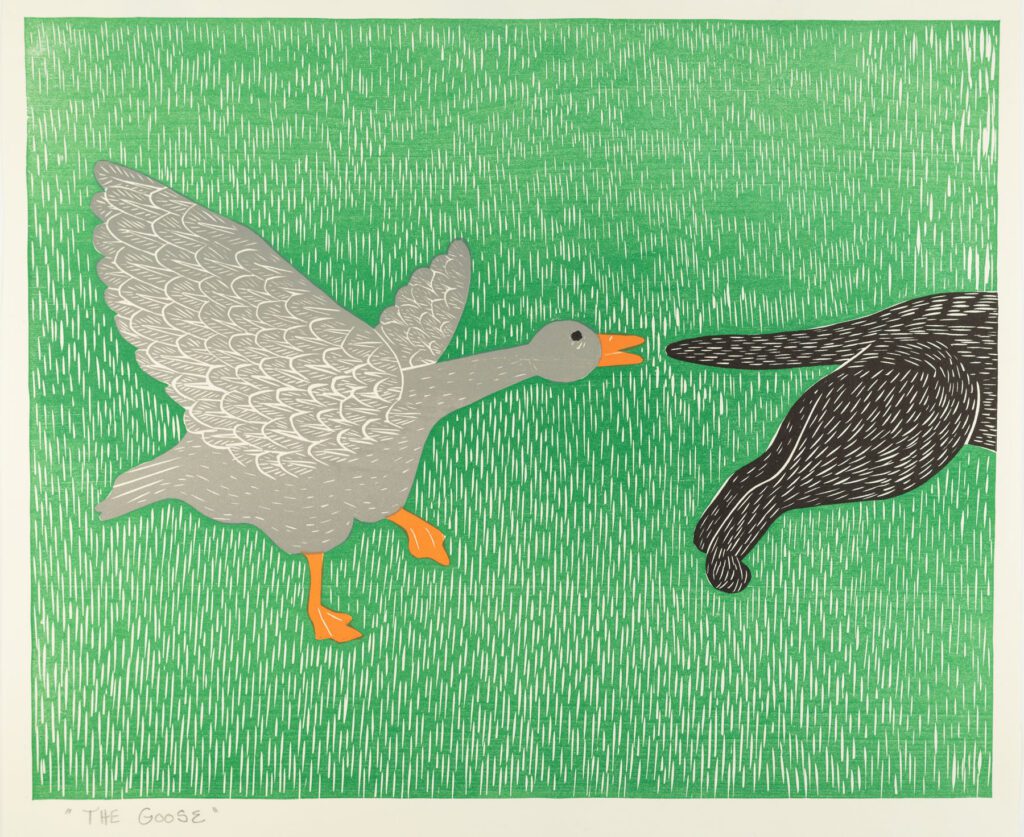

The Goose [Diptych], 2002

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.24a&b

Huneck wrote more than a dozen children’s books illustrated with his woodcut prints, which remain popular for readers of all ages today. Documenting the adventures of the artist’s adored black Labrador retriever, Sally, and her friends, Huneck’s prints capture the dogs’ moxie and enjoyment of life’s simplest pleasures. Defying the confines of the paper’s edge, The Goose expands the scene of a wild goose chasing after Sally and her Golden retriever friend, Molly. The action-packed diptych, which Huneck included in the publication Sally Goes to the Farm, captures movement with various directional lines demarcating the animals’ fast, forward action in contrast to the still, vertical blades of grass.

The Waiting Room, 2003

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.8

The Wagon, 2002

Woodcut print

Collection of Shelburne Museum, Gift of the Friends of Dog Mountain, 2022‑3.7

Huneck’s attention to composition, color, and texture is vital to his artistic practice; simple forms, bold colors, and a flatness of depth distinguish his work. Favoring emotive creativity over traditional or formal academic techniques, Huneck’s work intentionally shares aesthetic similarities with American folk art. “I found my palette as an antiques picker,” the artist affirmed, and indeed his work often features colors that are either chromatically intense or muted and more natural. Likewise, untrained artists often feature these distinct palettes by virtue of the fact that they are working with common household materials and paints available to them, such as Wilhelm Schimmel (American, 1817–1890), who brightly painted his whimsical woodcarvings with common house paints.