Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb gathered a collection of portraits in the late 1950s that was meant to “instill in those who visit a deeper understanding and appreciation of our [national] heritage.” Visages of America’s revolutionary forebears, like George Washington and John Scollay, hung alongside progressive portraits of 19th-century abolitionists William and Nancy Lawson as well as renderings of notable indigenous leaders like Seneca orator Sa-go-ye-wat-ha (also known by his English moniker, Red Jacket). These painted portraits complemented a wide range of material culture at the Museum, inflecting visitors’ understandings of and context for objects like still lifes, weathervanes, textiles, and folk art.

Shelburne Museum continues to collect intriguing objects that record the heritage and histories of American people. Many of these objects—like Luigi Lucioni’s My Father (1941) and Patty Yoder’s H is for Hannah and Sarah, A Civil Union (2000)—chart shifts and reconsiderations of the ways we think of ourselves as part of a larger American social fabric. All contribute to a fuller understanding of where we’ve come from and where we might be going.

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by The Donna and Marvin Schwartz Foundation and the Barnstormers at Shelburne Museum.

John Singleton Copley (American, 1738-1815)

John Scollay, 1760

Oil on canvas, 36 1⁄4 x 29 3⁄4 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Harry Shaw Newman, The Old Print Shop,

1959-275

A prominent member of Boston society, John Scollay was a savvy merchant who held positions ranging from fire marshall (1747–1782) to chairman of the Boston Board of Selectmen (1774–1790). A revolutionary and member of the Sons of Liberty, Scollay was also one of about 50 men who signed a letter to England’s King George III protesting the actions of British revenue officers.

Considered one of the finest artists in the American colonies, John Singleton Copley established his

career painting portraits of men like Scollay, members of Boston’s wealthy merchant class. A proper portrait requires a proper frame, and Copley was one of the first American artists to devise and market surrounds for his paintings. The gilded and carved Rococo-style frame that surrounds John Scollay is typical of Copley’s designs from about 1760 to 1772. Thanks in part to several old labels that remain attached, experts believe that this surround is probably original to the portrait.

Unidentified maker

George Washington on Horseback, early 19th century

Carved and painted wood, leather, and brass, 21 ½ x 21 x 7 in.

Museum purchase, 1950, acquired from Mary Allis, 1961-1.232

When Mrs. Webb purchased this object in 1943, art dealer Edith Halpert (1900–1970) wrote that it was “one of the most important sculptures discovered in the folk art tradition.” While Halpert originally marketed George Washington on Horseback as an 18th-century creation, it is more likely that this sculpture was inspired by a print after Thomas Sully’s 1819 oil painting The Passage of the Delaware (now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). A contemporary history painting, Sully’s canvas depicted General George Washington and his troops crossing the icy Delaware River from Pennsylvania to New Jersey on Christmas night, 1776. The next day Washington and his cadre would surprise English forces at the Battle of Trenton, winning a crucial victory for the American march toward independence.

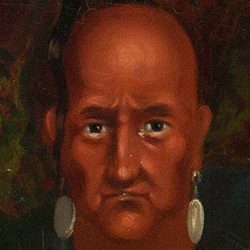

Unidentified artist (New York)

Red Jacket, Chief of Seneca Indians, ca. 1830

Oil on wood, 27 1⁄2 x 44 7/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Harry Shaw Newman, The Old Print Shop,

1961-1.60

In this painting, a youthful Native American man reclines in a wooded enclave. Dressed in a bright blue coat with gold fringe, vermilion stockings, and moccasins, the sitter wears a large silver pendant. Painted with thick, colorful oils on a wooden panel, there are no marks or signatures indicating the name of the artist, the identity of the subject, or this curious portrait’s date of execution.

Some scholars have argued that this may be a portrait of the renowned Seneca leader and orator Sa-go-ye-wat-ha (c. 1750–1830). Better known as Red Jacket, this legendary member of the Iroquois Confederacy and spokesperson for native sovereignty during the early national period received his English nickname because of the British military coat he wore following the American Revolution. The silver medal around the subject’s neck was presented by President George Washington during a 1792 trip to Philadelphia in which Red Jacket led a delegation of Iroquois leaders to assert tribal grievances and claims with federal government officials.

Unidentified maker (Pennsylvania)

TOTE, 19th century

Painted sheet iron, 51 x 31 x 1 3⁄4 in.

Bequest of Electra Havemeyer Webb, acquired from Edith Halpert, The Downtown

Gallery, 1941, 1961-1.138

Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb bought TOTE (pronounced “toh-tay”) from New York City’s Downtown Gallery in 1941. The gallery's owner, Edith Halpert (1900–1970), who dealt in both folk and contemporary American avant-garde art, regarded folk art as the ancestor of modern art, sometimes seeing in it modernist qualities. TOTE’s strong silhouette and flattened, reduced formal geometry—compositional strategies typical of post-Cubist of semi-abstract art in the early 20th century—likely appealed to Mrs. Webb’s penchant for combining folk forms with modern aesthetics. Eventually, a copy of TOTE was produced for use as a weathervane on the roof of the Museum's Horseshoe Barn. In the replica, however, the name “WEBB” replaced “TOTE.”

“TOTE” stands for “Totem of the Eagle,” the symbol of a fraternal organization, The Improved Order of Red Men. Founded in the early 19th century, the group appropriated Native American names, expressions, and symbols that were—incorrectly—assumed to have been used by indigenous people. Despite the society’s name, membership was limited to white males until 1974.

Attributed to Ammi Phillips (American, 1788-1865)

Portrait of a Quaker Woman, 1835-45

Oil on canvas, 36 1⁄4 x 30 1⁄4 in.

Gift of James and Susan Wanner, 2002-32

Born in northwestern Connecticut, Ammi Phillips painted portraits in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York from about 1811 until the 1860s. Scholars have estimated that at least 600 portraits came from his hand. By the 1840s, Phillips was living in Dutchess County, New York, where Quakers had settled as early as the mid-18th century.

The sitter in this portrait, so-named “Quaker Woman” by the painting’s original owner, wears clothing traditionally associated with the Society of Friends, the formal name of the Quakers. Her tightly-fitted cap with broad brim, transparent shawl, and neckerchief were typical of the plain attire adopted by Quaker women identifying them as members of the religious sect. The Society of Friends took great pride in educating young women—a progressive notion for the mid-19th century. While images of the Bible were included in many 19th-century portraits, its presence in this composition likely alludes to the sitter’s literacy.

Erastus Salisbury Field (American, 1805-1900)

Louisa Ellen Gallond Cook, 1838

Oil on canvas, 34 3/8 x 28 7/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1959-265.18

Born in northwestern Connecticut, Ammi Phillips painted portraits in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York from about 1811 until the 1860s. Scholars have estimated that at least 600 portraits came from his hand. By the 1840s, Phillips was living in Dutchess County, New York, where Quakers had settled as early as the mid-18th century.

This likeness of Louisa Ellen Gallond Cook is an unlikely survival, rescued from the Petersham, Massachusetts, town dump in the fall of 1952 by local high school teacher Guy A. Bagley. After seeing a painting bearing similar characteristics at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, Bagley sold this picture to collector Maxim Karolik, and Karolik sold the portrait to Shelburne Museum. Executed by itinerant artist Erastus Salisbury Field, it is one of a group of portraits of the Gallond family painted circa 1838. Interestingly, many of these compositions include harbor scenes in the background—yet Petersham is located far from the Atlantic coast in western Massachusetts. It is likely that these scenes were idealized views of an imaginary seaport, referencing the prosperous seafaring family into which Louisa married.

William Matthew Prior (American, 1806–73)

Mrs. Nancy Lawson, 1843

Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 25 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1959-265.34

William Matthew Prior (American, 1806–73)

William Lawson, 1843

Oil on canvas, 30 1⁄4 x 25 1⁄4 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1959-265.35

Regarded by many to be William Matthew Prior’s masterpieces, the likenesses of the Lawsons have become icons of American folk portraiture. William Lawson (1807–1854) was a used clothing dealer in Boston where he was a prominent advocate of the abolitionist cause and an adherent to the philosophies of William Miller, one of the forebears of Adventism who encouraged equality among races and genders and considered slavery a sin. Born in Maine, Nancy Lawson (1810–1854) was a cousin to a Millerite preacher. The artist likely came to know the sitters through Millerite connections in Boston. Prior signed both portraits with his name and the names of the sitters on the front of the canvases—a courageous, and potentially dangerous, action for both artist and subjects. Although Boston was the epicenter of abolitionism in New England, racism still existed at all levels of society; the signature is both an artistic statement and an expression of the painter’s moral values.

Eastman Johnson (American, 1824-1906)

Family Cares, 1873

Oil on wood, 15 x 11 1/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Harry Shaw Newman, The Old Print Shop,

1956-696

Family Cares, a small interior painted by outspoken abolitionist Eastman Johnson, presents a challenging picture of post-bellum life in 19th-century America. A young girl—likely modeled by the artist’s daughter, Ethel – concentrates on threading a needle with a long, dark length of string, cradling a large doll in her lap. Upon closer inspection, more disturbing details emerge. The broken toys at the child’s feet include the jagged, decapitated head of a white doll; a “Mammy” doll—a racialized caricature meant to represent African American women—that hangs from a cord attached to a chair, a disturbing reference to lynching; and a small white doll whose clothes have been removed, perhaps signifying sexual violence. The young girl’s role in the fate of her toys remains unclear. Perhaps she is responsible for the mess at her feet, cruelly indifferent to the implied violence around her. Alternatively, her close concentration on her needle and thread may indicate that she is working to repair her dollies.

Exhibited at New York’s Artists’ Fund Society in January 1873, this picture remains something of an enigma. Related to a series of works by Johnson highlighting scenes from the home front both during and after the Civil War, the mangled dolls might represent women whose lives and families were torn asunder as husbands and sons were sent off to fight.

John Frederick Peto (American, 1854-1907)

Ordinary Objects in the Artist's Creative Mind, 1887

Oil on canvas, 56 3/8 x 33 1⁄4 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1959-265.33

The palette and the cornet bracket the life and career of John Frederick Peto. Trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Peto exhibited his work frequently as a young man. By 1889, however, the artist had retreated to Island Heights, New Jersey, a Methodist camp meeting community. There he built a studio, took in boarders, played in the village band, and produced paintings for tourists who summered on the Toms River. In Ordinary Objects in the Artist’s Creative Mind, Peto’s studio door acts as an autobiographical landscape in which the artist carefully balances suggestive clutter and order while displaying objects—such as the cornet and the painter’s palette—which symbolize his dual occupations and hint at his life story.

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926)

Louisine Havemeyer and her Daughter Electra, 1895

Pastel on wove paper, 24 x 30 1⁄2 in.

Museum purchase, 1996-46

In 1895, Louisine and young Electra Havemeyer visited Mary Cassatt in her new home northwest of Paris. During their visit, mother and daughter posed for this touching double portrait. Nestled on her mother's lap, Electra is dressed in a striped pinafore ready for play while Louisine is garbed in a more modern dress fitting a lady at the head of her household. Mother and daughter are lost in thought and their arms encircle one another creating a heart shape while their hands meld together in the foreground of the image. Cassatt employed pastel—a medium she had recently become increasingly interested in after seeing the works of 18th-century French pastellists at the Louvre—to create her subjects’ soft, rosy cheeks and shiny hair. She considered pastel “the most satisfactory medium for (depicting) children.”

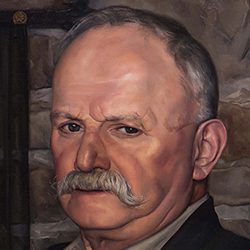

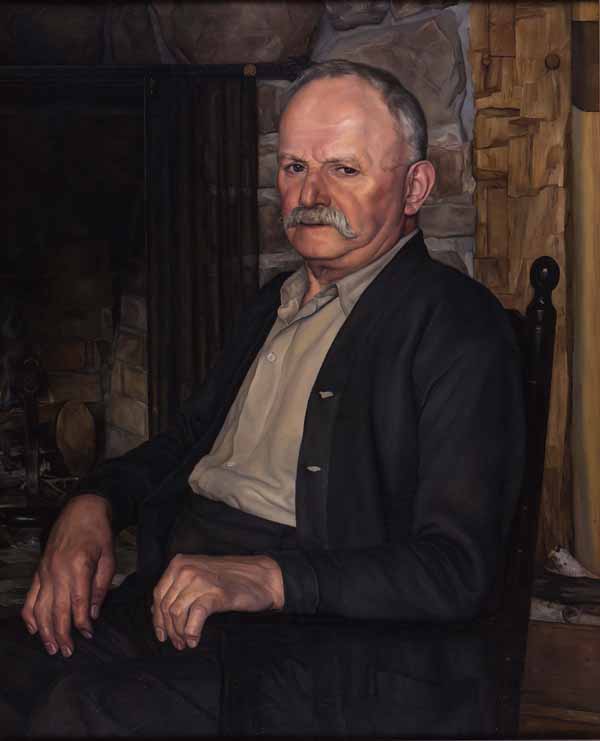

Luigi Lucioni (American, b. Italy, 1900-88)

My Father, 1940-70

Oil on canvas, 34 1⁄4 x 28 1⁄4 in.

Bequest of Luigi Lucioni, 1988-27.1

Born in Italy, Luigi Lucioni immigrated to the United States in 1911 via Ellis Island. After training at Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design, a friendship with patron Electra Havemeyer Webb drew the artist to Shelburne, Vermont, in 1930. In 1939 Lucioni purchased a home and studio in Manchester, where he spent summers for the rest of his life and taught at the Southern Vermont Arts Center.

The artist felt that this likeness of his father, Angelo Lucioni, was his best portrait. Trained as a coppersmith, Angelo arrived in the United States in 1906 to establish a home for his family in New York City. Recalling Angelo, Luigi commented “I didn’t appreciate my father very much when I was young, but now I know he had a great deal of courage to come to America from Italy. He was 75 years old when I painted this portrait, and he had a hard, bluff exterior about him... He wanted to be very masculine like most Italian men of the time.”

Patty Yoder (Tinmouth, Vermont, 1943-2005)

H is for Hannah and Sarah, A Civil Union, 2000

Wool and cotton, 32 x 32 1⁄2 in.

Gift of the Yoder Family, 2010-98.24

American rug hooker Patty Yoder conceived of her designs as “paintings with wool to be hung and enjoyed as art.” The Alphabet of Sheep, a series of 33 hooked rugs that was also published as a book in 2003, was a project that combined two of Yoder’s favorite things: illustrated alphabet books and the sheep, goats, and llamas at Black House Farm, her Tinmouth, Vermont, home. While these rugs celebrate Patty’s friends, family, and animals, they also connect Yoder’s work to a long tradition of rug hooking in New England.

In 2000, Vermont’s state Supreme Court ruled that same-sex couples were entitled to the same rights as opposite sex couples, thus making Vermont the first state in the U.S. to give full marriage rights to same- sex couples. Writing about H is for Hannah and Sarah, A Civil Union, Yoder commented, “I hooked this rug with great pride in the state of Vermont and with great hope for the future of the United States of America.”