Electra Havemeyer Webb’s affinity for bold, decorative patterns is visible throughout Shelburne Museum—on the objects she collected, in the unique displays she created and built into the architecture of the exhibition galleries she designed. Mrs. Webb inherited her sophisticated use of patterns from her parents. She developed her eye growing up in the densely patterned Aesthetic Movement interiors of her family’s New York City home, which blended ornamental motifs from different cultures around the world. Although Mrs. Webb’s collecting interest in Americana diverged from her parents’, she shared their preference for mixing and layering patterns. At the Brick House, her Vermont home, she experimented with presentation techniques for her collections that mixed and matched, and transposed seemingly discordant patterns into cohesive displays that profoundly influenced the look and spirit of Shelburne Museum.

Pattern in Music

A playlist by Ray Vega, musician and host of VPR’s Friday Night Jazz

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by The Donna and Marvin Schwartz Foundation and the Barnstormers at Shelburne Museum.

Unidentified makers

Assortment of Hat and Bandboxes, ca. 1825-50

Printed paper on pasteboard and wood, average 12 x 17 1⁄2 x 14 1⁄2 in.

28 Group

Carried by trendy young women and men, bandboxes were fashionable carryalls used as both portable luggage and stackable storage containers. Made of either thin bent wood scabbards or more commonly pasteboard, bandboxes were covered in fanciful wallpapers or specially printed papers, the patterns of which were designed to appeal to a wide range of tastes of style conscious consumers. Pattern themes ranges ranged from floral and romantic classical scenes to hunting, modes of transportation, and architecture. Some paper patterns commemorated politicians, national landmarks, and newsworthy events such as the Great Moon Hoax of 1835.

Putnam and Roff (Hartford, Connecticut, 1821-24)

Eagle with Banner (detail), 1821-24

Pasteboard box, 10 5/8 x 16 1/4 x 12 3/8 in.

Museum purchase, 2012-16

Unidentified maker

Peep at the Moon (detail), ca. 1840

Pasteboard and decorative paper, 11 1/2 x 18 1/8 x 14 1/8 in.

Museum purchase, 1958-242.10

Unidentified maker

Floral Design Bandbox (detail), date unknown

Pasteboard and decorative paper, 11 3/4 x 18 5/8 x 13 1/4 in.

Museum purchase, 1956-631.7

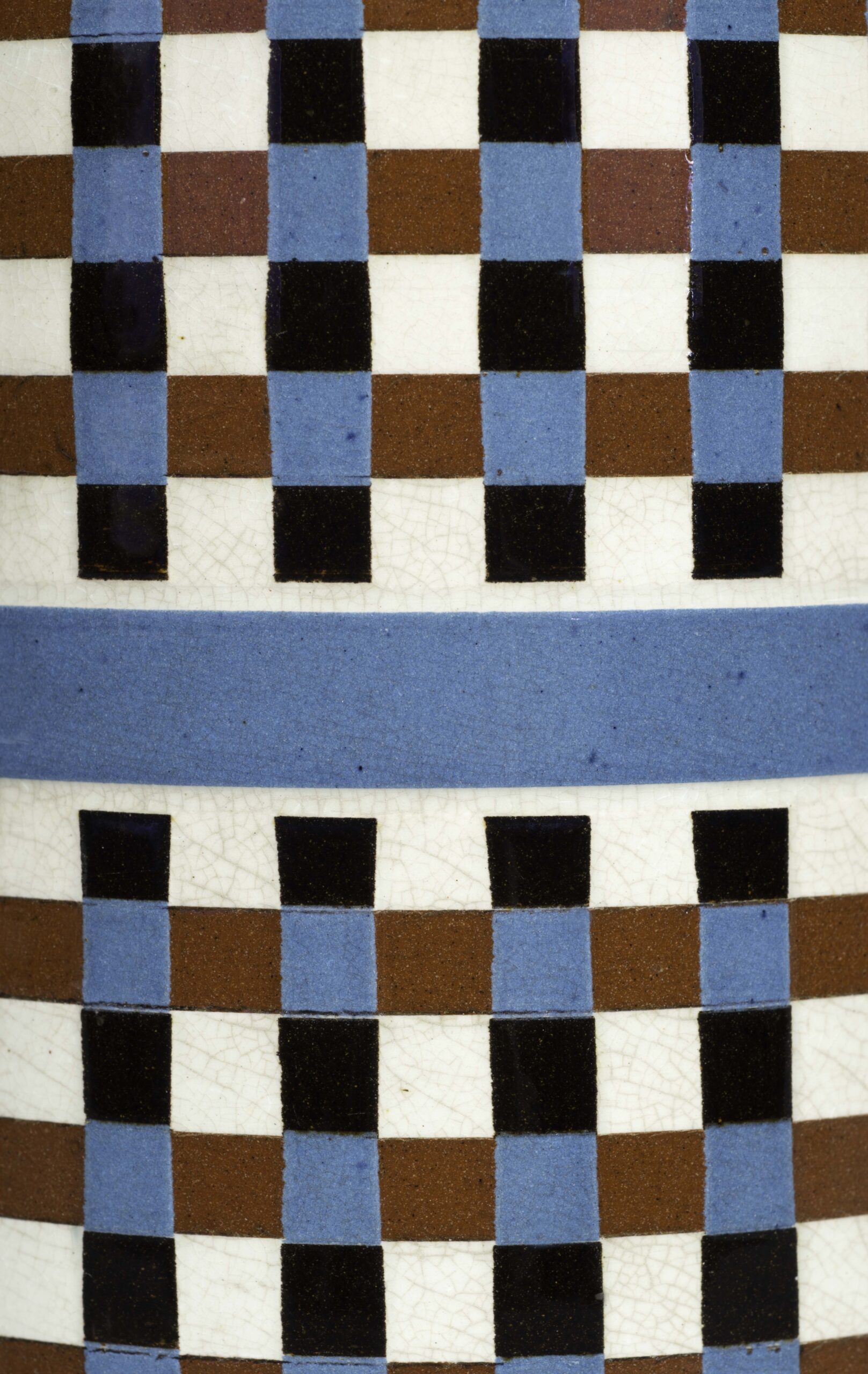

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

Assortment of Mochaware, early 19th century

Earthenware and slip, between 3 x 5 1/2 in. and 8 3/4 x 6 x 9 in.

31.16 Group

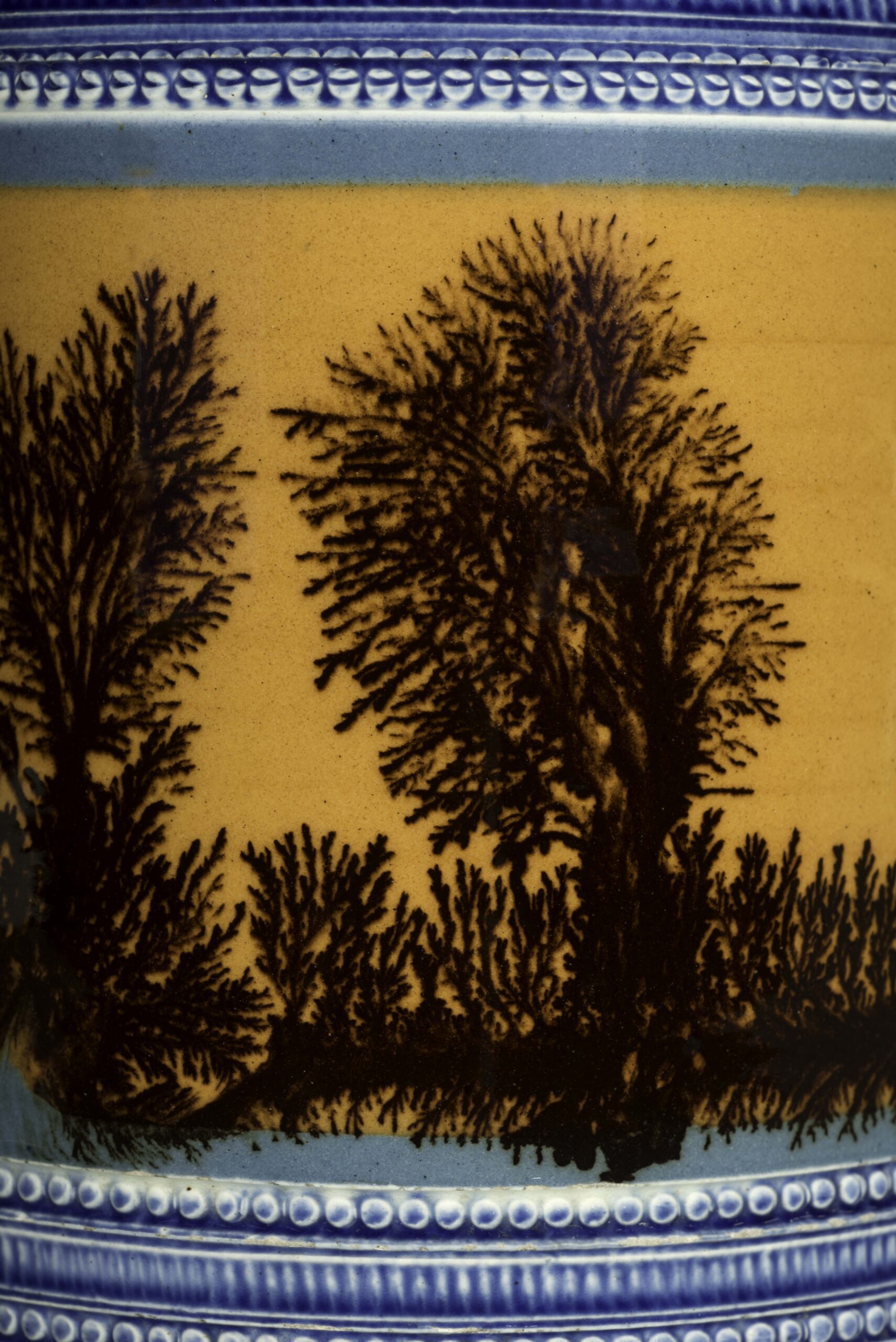

With fanciful patterns produced by a combination of both industrial technology and handcraftsmanship, mochaware is a generic term for slip-decorated utilitarian ceramics mass-produced in the Staffordshire region of England from the late-1700s through the mid-1800s. Mechanical lathes equipped with special sprocket and crown-shaped cams produced geometric and “diced” patterns into the surface by scraping away the different layers of colored slip. The vessels covered in tri-colored dots or “cat’s eyes” were decorated with a three-chambered slip cup that produced droplets on the surface as the piece rotated on a lathe, which, if slowed down produced the cable or “earthworm,” pattern. The dendritic, or tree-like, decoration was applied directly by the artisan with a paintbrush, allowing gravity and the motion of the lathe to help the liquid to branch outwards. The presence of the human hand in each of these techniques resulted in irregularities or “slip-ups,” which make each manufactured piece a unique work of art.

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

Mochaware Mug with Engine-Turned Decoration (detail), early 19th century

Earthenware and slip, 5 13/16 x 4 3/8 x 6 in.

Gift of Edith C. Blum, 1976-74.22

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

Mochaware Mug with Dendrite Decoration (detail), early 19th century

Earthenware and slip, 6 x 4 3/4 x 6 in.

Gift of Edith C. Blum, 1976-74.24

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

Mochaware Bowl with Cat's Eyes (detail), ca. 1820

Earthenware and slip, 3 x 5 1/2 in.

Bequest of Harry T. Peters, Jr., 1982-5.260

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

Mochaware Pitcher with Earthworm Decoration (detail), early 19th century

Earthenware and slip, 8 x 5 7/8 x 8 7/8 in.

Gift of Edith C. Blum, 1976-74.18

Joseph Whiting Stock (American, 1815-55)

Jane Henrietta Russell, 1844

Oil on canvas, 48 3/8 x 36 1/4 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1959-265.40

Nineteenth century American interiors were alive with pattern, as the wreath design in the floorcovering, the stylized flowers on the lid of the game box, and exuberant figuring of the wood grain of the furniture in this portrait attest. The same cannot be said for the subject of this painting. The sad and macabre fact was that at the time Stock painted this likeness of young Jane Henrietta, she had passed away. Stock, who was paralyzed from the waist down from an oxcart accident and used a special wheel chair that allowed him to sit up and be mobile, traveled throughout New England painting portraits on commission, advertising his experience in “painting from the corpse.”

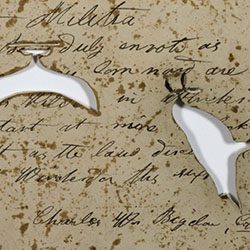

Charles E. “Shang” Wheeler (Stratford, Connecticut, 1872-1949)

Mallard Drake & Hen Decoy, 1922-23

Wood, paint, glass, metal, and leather, 5 x 7 1/2 x 17 1/4 in. and 5 1/8 x 6 x 17 5/8 in.

Gift of J. Watson, Jr., Harry H., and Samuel B. Webb, 1952-192.2&3

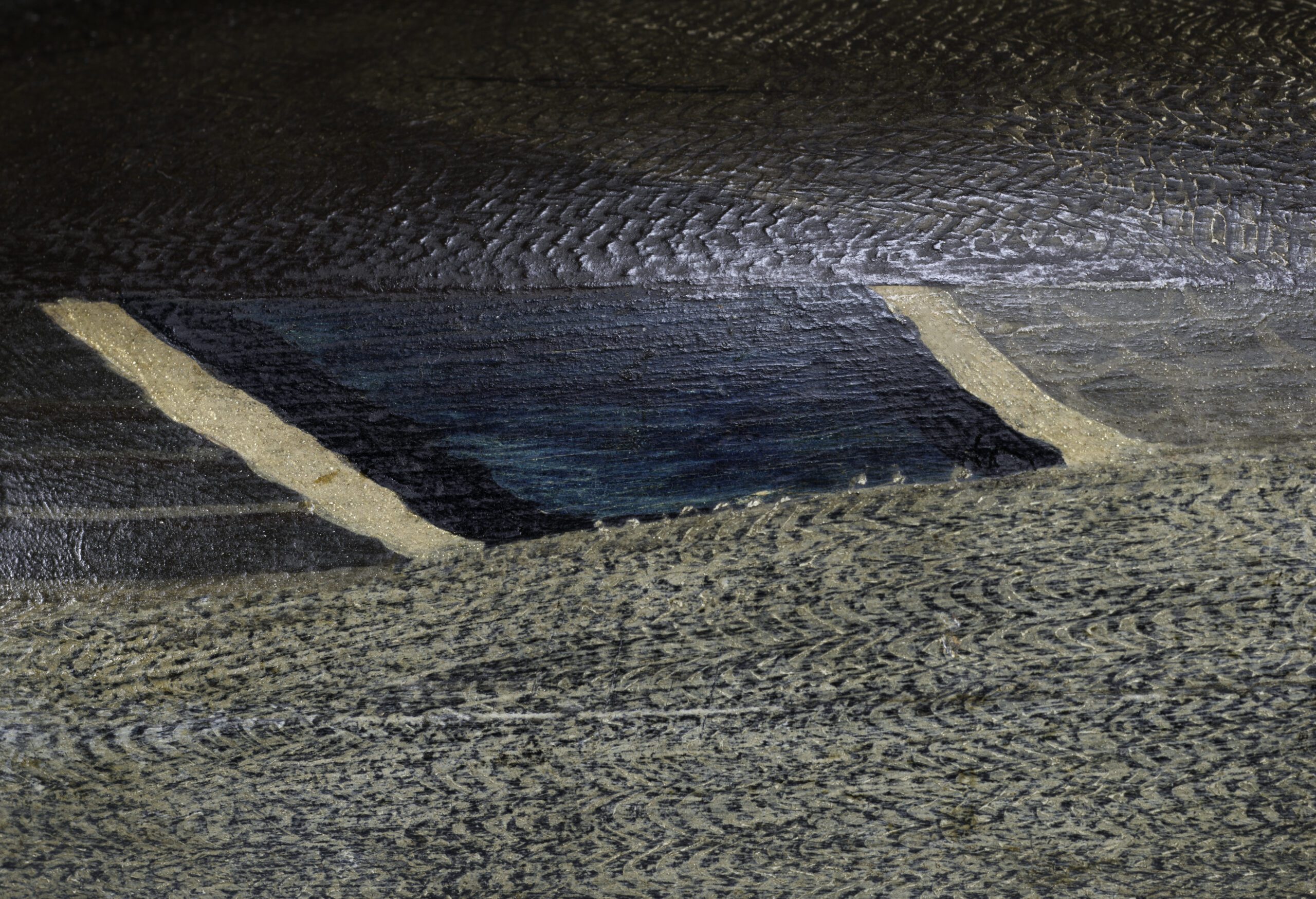

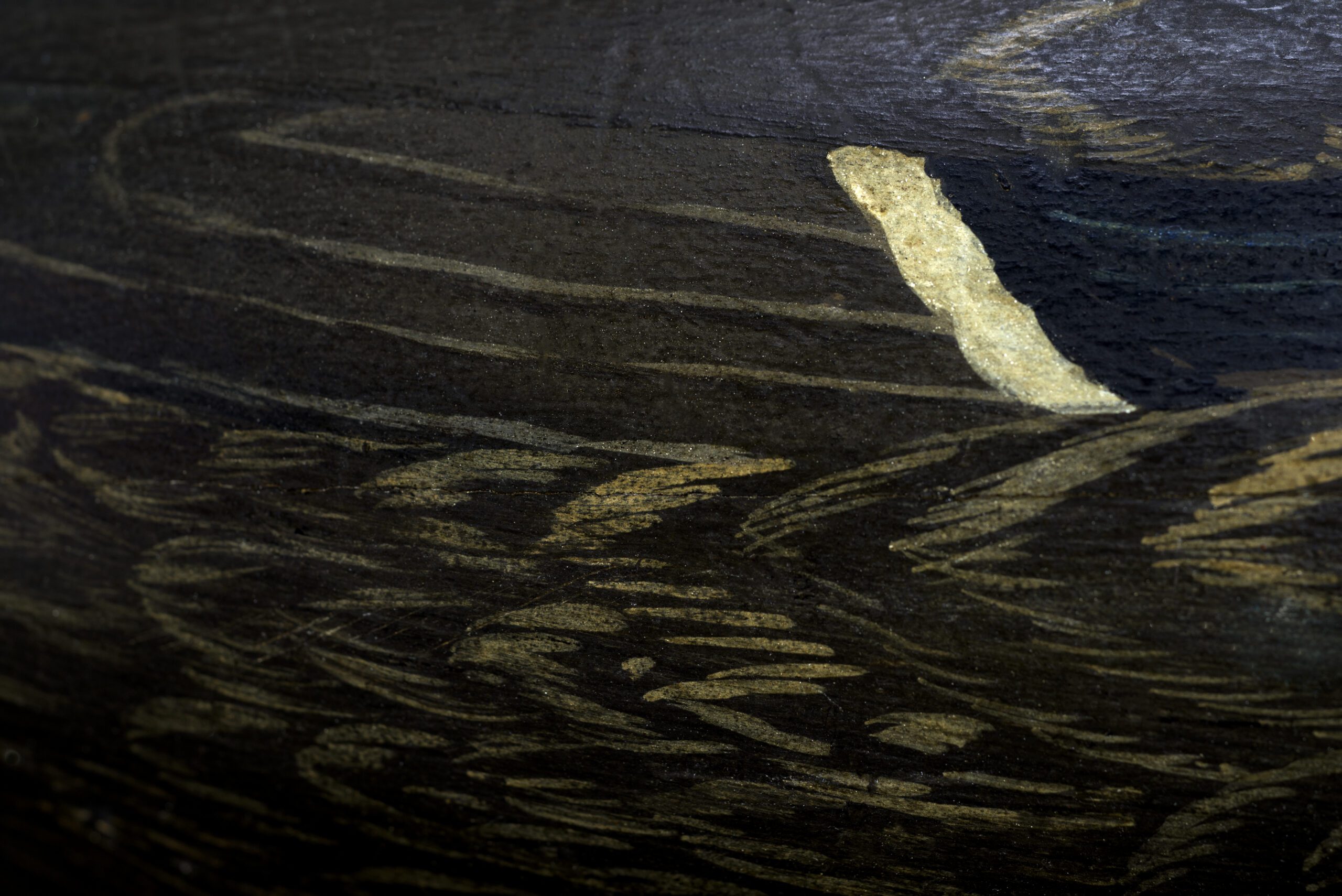

Considered one of the leading decoy carvers of the Stratford School, Shang Wheeler was an avid hunter and naturalist who used his intimate knowledge of wildfowl anatomy and behavior acquired in the field to create his realistic portrayals of game birds. Wheeler’s attention to detail is apparent in the lifelike painting of the plumage patterns on this pair of mallards, which took Grand Prize at the Bellport Long Island Decoy Show in 1923. The drake is covered in Wheeler’s characteristic combed feather technique.

A devoted conservationist, Wheeler, as a two-term member of the Connecticut House of Representatives and one-term state Senator, helped pass groundbreaking anti-pollution and wildlife preservation legislation.

Charles E. “Shang” Wheeler (Stratford, Connecticut, 1872-1949)

Mallard Drake Decoy detail, 1922-23

Wood, paint, glass, metal, and leather, 5 x 7 1/2 x 17 1/4 in.

Gift of J. Watson, Jr., Harry H., and Samuel B. Webb, 1952-192.2

Charles E. “Shang” Wheeler (Stratford, Connecticut, 1872-1949)

Mallard Hen Decoy detail, 1922-23

Wood, paint, glass, and leather, 5 1/8 x 6 x 17 5/8 in.

Gift of J. Watson, Jr., Harry H., and Samuel B. Webb, 1952-192.3

Ellen Fullard Wright (Providence, Rhode Island, 1818-89)

Applique and Pieced Star of Bethlehem and Ships Wheel Quilt with Baskets and Birds, 1870-89

Cotton, 94 3/4 x 73 3/4 in.

Museum purchase, 1991-29.1

A variation of the “Broken Star” pattern, the dizzying constellation at the center of this quilt can attribute the origins of its design to the unexpected results of cutting-edge scientific experimentation in the early years of the 19th century. In 1812 Scottish physicist, Sir David Brewster (1781-1868) accidentally invented the kaleidoscope (Greek for “beautiful image viewer”) while conducting a series of investigations into the polarization of light. Although considered a toy today, the kaleidoscope had a profound impact on the visual culture in Britain and the United States immediately following its invention as a tool able to “fancy to itself things more great, strange, beautiful than the eye ever saw.” When spied through the lens of a kaleidoscope, small shards of colorful glass danced before the eye, transforming into “stars, glittering snowflakes, and shimmering diamonds,” which inspired vertiginous decorative patterns for glass, ceramics, furniture, and quilts.

Enoch Wood & Sons (Staffordshire, England, 1818-45)

Niagara Falls from the American Side, date unknown

Transferware, 1 3/4 x 14 3/4 x 11 1/8 in.

Museum purchase, 2004-24.4

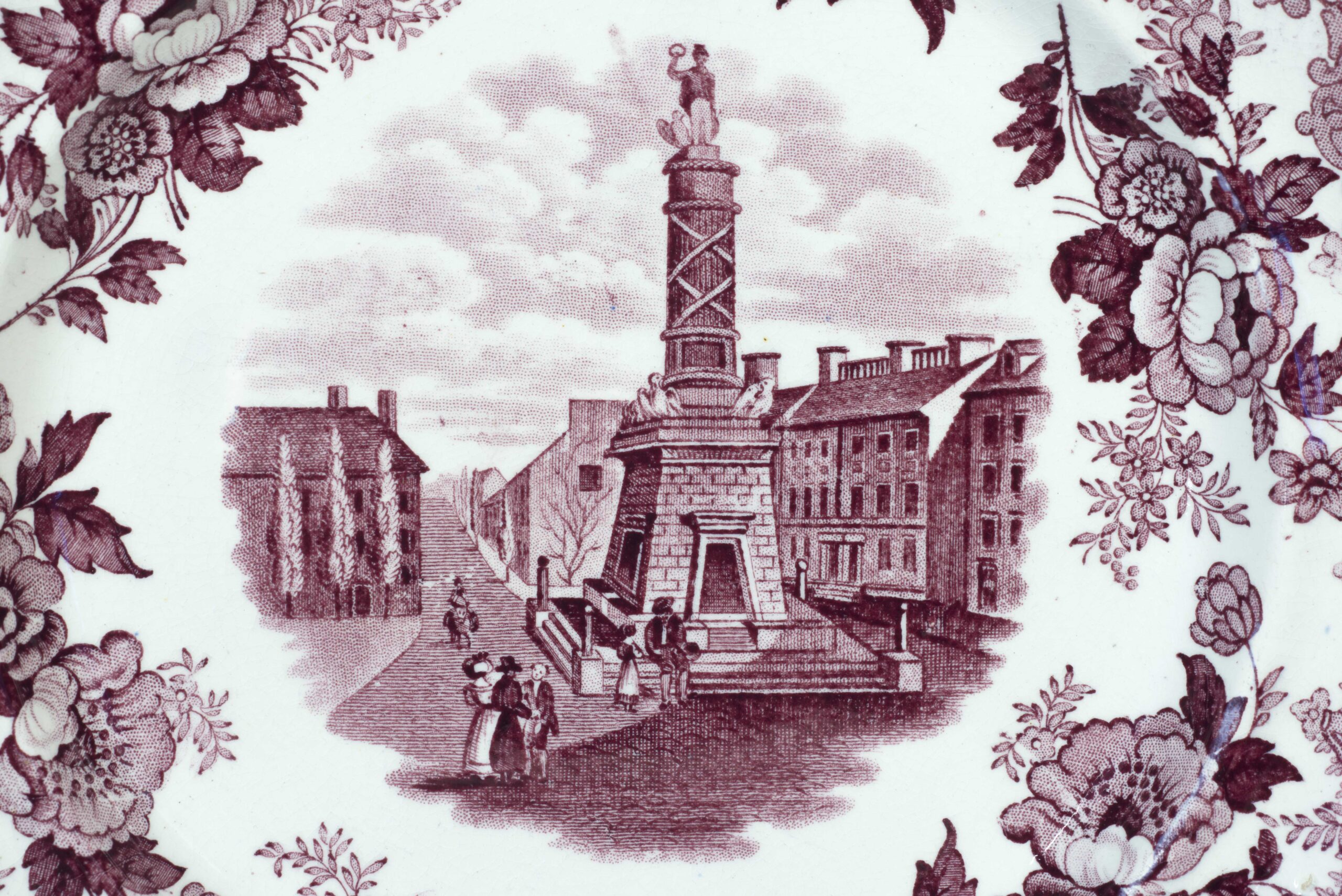

Long before the Franklin Mint began issuing collectible plates in the mid-20th century, the Staffordshire potteries of" content="Great Britain produced commemorative transfer-printed dinnerware sets, designed to appeal specifically to American consumers. Popular in the United States in the years immediately following the War of 1812 when trade between the two nations resumed, Staffordshire transfer wares were produced with a variety of American scenes in a rainbow of colors. Based on popular prints, these patriotic patterns were an early example of market targeting. They featured landscape views, important landmarks, both natural (Niagara Falls) and manmade (the Erie Canal), famous monuments (the Baltimore Battle Monument) and structures (the White House), as well as historical events (the burnt ruins of New York’s Merchant Exchange).

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

Erie Canal at Buffalo, ca. 1800-50

Transferware, 1 1/16 x 10 7/16 in.

Museum purchase, 1965-72.12

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

Battle Monument Baltimore, date unknown

Transferware, 7/8 x 9 in.

Museum purchase, 1965-45.2

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

The President's House Washington, date unknown

Transferware, 1 1/16 x 10 5/16 in.

Museum purchase, 1966-34.4

Staffordshire Potteries (Staffordshire, England)

Great Fire City of New York: Burning of the Merchants' Exchange, ca. 1835

Transferware

Gift of J. Watson Webb, Jr., 31.10-242.2

Unidentified maker (Probably rural Massachusetts)

Harvard Chest, 1700 25

Painted pine and brass, 43 3/4 x 38 7/8 x 20 3/4 in.

Gift of Katharine Prentis Murphy and Edmund Astley Prentis, 1956 694.8

This coverlet, with its interior field of large roses and foliate designs framed by a border of trees and leaves, is the 19th-century equivalent of contemporary CGIs (computer generated images). Produced on a Jacquard loom, named after French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard, this coverlet’s complex woven pattern was executed using a system of punch cards that, “governed the raising and lowering of the warp threads in predetermined sequence that created the design.” Introduced to America as an attachment to existing looms in the mid-1820s, Jacquard’s invention revolutionized the weaving industry. Non-skilled workers could quickly produce complex patterns that had previously taken skilled artisans weeks or months to complete.This coverlet, with its interior field of large roses and foliate designs framed by a border of trees and leaves, is the 19th-century equivalent of contemporary CGIs (computer generated images). Produced on a Jacquard loom, named after French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard, this coverlet’s complex woven pattern was executed using a system of punch cards that, “governed the raising and lowering of the warp threads in predetermined sequence that created the design.” Introduced to America as an attachment to existing looms in the mid-1820s, Jacquard’s invention revolutionized the weaving industry. Non-skilled workers could quickly produce complex patterns that had previously taken skilled artisans weeks or months to complete.

James Goold Co. (Albany, New York, 1813-1913)

Albany Pony Sleigh, ca. 1885

Wood, metal, leather, velvet, and wool, 53 x 50 x 87 in.

40-S-26

Analogous to the elaborate custom automotive paint jobs of today, the plaid patterns located on the central panels of this swell-body sleigh were meticulously hand painted, layer by layer. Tartan plaids composed of “broad stripes of different shades of green, running diagonally...crossed at right angles by other green stripes, equally broad,” were notoriously complicated and time consuming to produce, requiring a steady hand and patience. However, when done correctly, the overall effect could be quite pleasing. An advice column published in the carriage-makers’ trade magazine Hub in 1885 counseled vehicular painters against wasting time on the technically difficult decorative technique, stating “There are means of making a job look well, without spending so much time in plaid work...and this should be looked to.”

Green Mountain Iron Company (Brandon, Vermont, 1810-55)

Parlor Stove, ca. 1840-50

Cast iron, 41 5/8 x 25 x 17 3/4 in.

Gift of David Wells, 1979-37

The bas relief acanthus leaves, anthemions, lyres, temple façades, and other ornamental patterns cast into the surface of this Grecian-style, double-chamber parlor stove served a functional as well as decorative purpose. These raised designs increased the surface area of the stove which in turn amplified the thermal output that radiated through the highly conductive iron. The four hollow Corinthian columns functioned as flues that allowed the hot air produced in the firebox to circulate into the upper chamber producing more heat for the commodious parlors characteristic of Greek-Revival houses.

Unidentified maker

George Washington New Year’s Cake Board and Cookie Mold, early 19th century

Carved wood, 1 1/8 x 24 7/8 x 14 3/4 in.

Museum purchase, 1953-1043

In his eulogy for George Washington, Congressman and Revolutionary War General Henry “Light Horse” Harry Lee described the President as, “First in war—first in peace—and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” Lee could have added first “American celebrity” to the list of Washington’s accolades. Before and especially following his death, George Washington’s likeness was reproduced on every conceivable consumer product, eagerly purchased by a grateful nation. Based on Nathaniel Currier’s popular print titled “Washington’s Reception by the Ladies, on Passing the Bridge at Trenton, New Jersey”, this cake board depicts the President on horseback raising his hat to crowds of women.

Carved from mahogany, large cake boards such as this example were used to produce gingerbread cakes, which were displayed publicly on New Year’s Day as part of an old Dutch tradition. Both the board and the dough were kept cold, on ice, before they were placed in a press or rolled by hand.

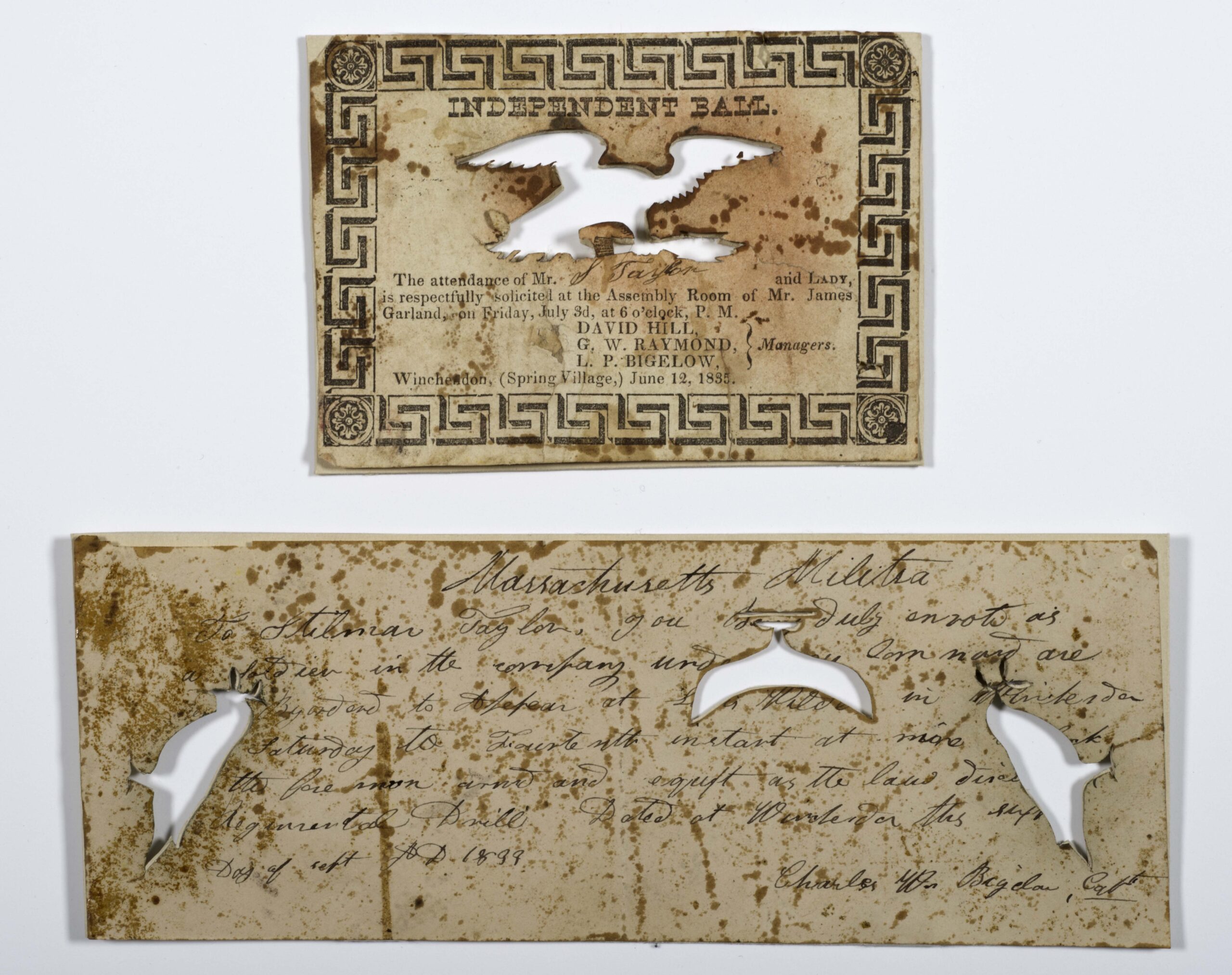

Stillman Taylor (Winchendon, Massachusetts, active 1825-40)

Stencil Box and Kit, 1825-40

Painted wood and mixed media

Museum purchase, 2004-10

An itinerant decorator for hire, Stillman Taylor carried this stencil kit as he traveled throughout the region between Hampshire County, Massachusetts and Cheshire County, New Hampshire, applying “Fancy” ornamentation for pattern-crazed middleclass households. Taylor’s repertoire included more than one hundred stencils, many of his own unique design, which he used to apply painted and gilded surface decoration to walls, floors, furniture, and textiles. Several of his hand-cut stencils were made from recycled paper, which included pages from arithmetic problem books, account ledgers, and personal correspondence.

Henry Leach for Cushing & White Co. (Waltham, Massachusetts)

Liberty weathervane pattern, 1879

Carved and painted wood with gilding and metal, 45 1/2 x 40 1/2 x 13 in.

Museum purchase, 1949, acquired from Edith Halpert, The Downtown Gallery,

1961-1.128

Mrs. Webb purchased this carved wood figure of Liberty from Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery in New York City in 1941. Carved by artisan Henry Leach, this one-of-a-kind work of art, was originally used by the Cushing & White Co. of Waltham Massachusetts as a pattern to mass produce weathervanes. The three-dimensional sculpture served as a master positive from which negative molds were cast. These molds were in turn used to make the company’s popular copper weathervanes.