I call [Mary Cassatt] my fairy godmother of my collection, for the best things I own have been bought on her judgement and advice.

—Louisine W. Havemeyer

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844-1926) is unquestionably one of the most highly recognized Impressionist artists. Celebrated, both today and during her time, she created a prolific body of work—paintings, pastel drawings, and prints— while living abroad in France, often capturing the private, domestic lives of women in this new painterly, modern, and emotive style. Cassatt’s lesser-known role came as fine arts advisor to her friends and family. For over 50 years, Cassatt expended significant energy cultivating a new market for Impressionism and securing a place for these works of art in collections across the globe. The art Cassatt helped export to America were some of the first seen by this new public. While Cassatt advised numerous collectors —from her family members to captain of industries—her good friends, Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer (1855-1929) and Henry Osborne Havemeyer (1847-1907), were her constant, primary, and most inquisitive clients.

Working together for over five decades, with “Miss Cassatt ever ready to recommend, Mr. Havemeyer to buy, and I [Mrs. Havemeyer] to find a place for the pictures in our gallery” they amassed one of the world’s greatest art collections. Today, the majority of the Havemeyer’s collection resides at The Metropolitan Museum of Art; however, many of its gems were inherited by their youngest daughter, and Shelburne Museum founder, Electra Havemeyer Webb (1888-1960), and are now part of Shelburne Museum’s permanent collection.

Mary Cassatt’s Impressions: Assembling the Havemeyer Art Collection explores the enduring friendship between Cassatt and the Havemeyers and highlights archival anecdotes and primary sources detailing their acquisitions of Impressionist paintings, drawings, and sculptures based on Cassatt’s advice.

In 1874, at the impressionable age of 19, an enthusiastic Louisine Waldron Elder, later Havemeyer, accompanied by her two sisters, was studying abroad in Paris and attending Madame Del Sartre’s boarding school. While there, she was introduced to rising artistic star, Mary Stevenson Cassatt,11 years her senior. “When we first met in Paris, [Cassatt] was very kind to me, showing me the splendid things in the great city, making them still more splendid by opening my eyes to see their beauty through her own knowledge and appreciation,” Mrs. Havemeyer reminisced many decades later in her autobiography. “It seemed to me, no one could see art more understandingly, feel it more deeply, or express themselves more clearly than she did. She opened her heart to me about art while she showed me the great city of Paris.” With Cassatt’s tasteful eye and tap on the pulse of the Parisian art world, she guided Mrs. Havemeyer during their initial meetings to purchase modern art—works by Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Edouard Manet (1832-1883), and Cassatt herself—which would inform her, and later, her husband’s collecting interests.

Unidentified photographer

Mary Cassatt, Grasse, 1914

Gelatin silver print

Frederick A. Sweet research material on Mary Cassatt and James A. McNeill Whistler, 1872-1975. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

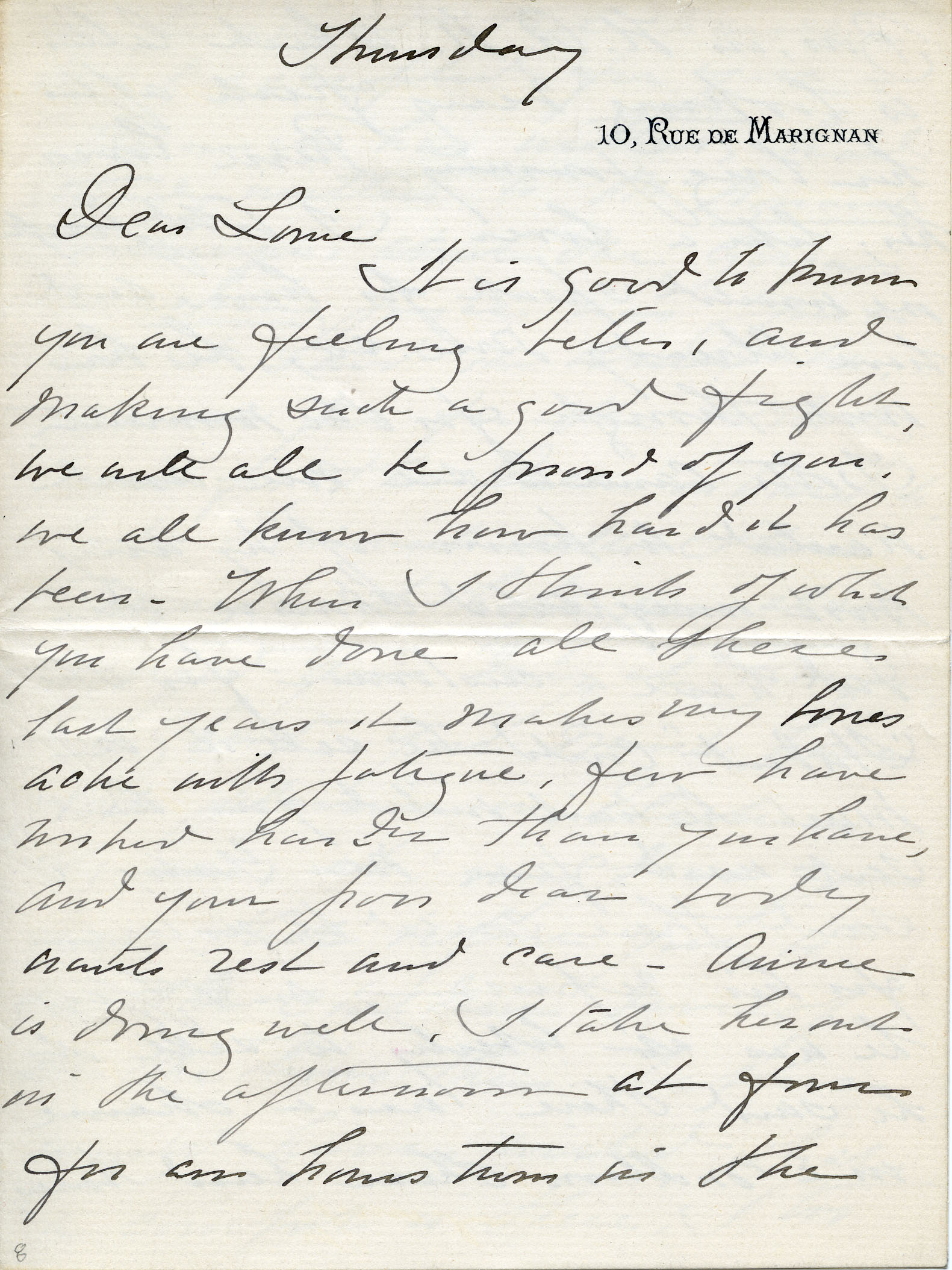

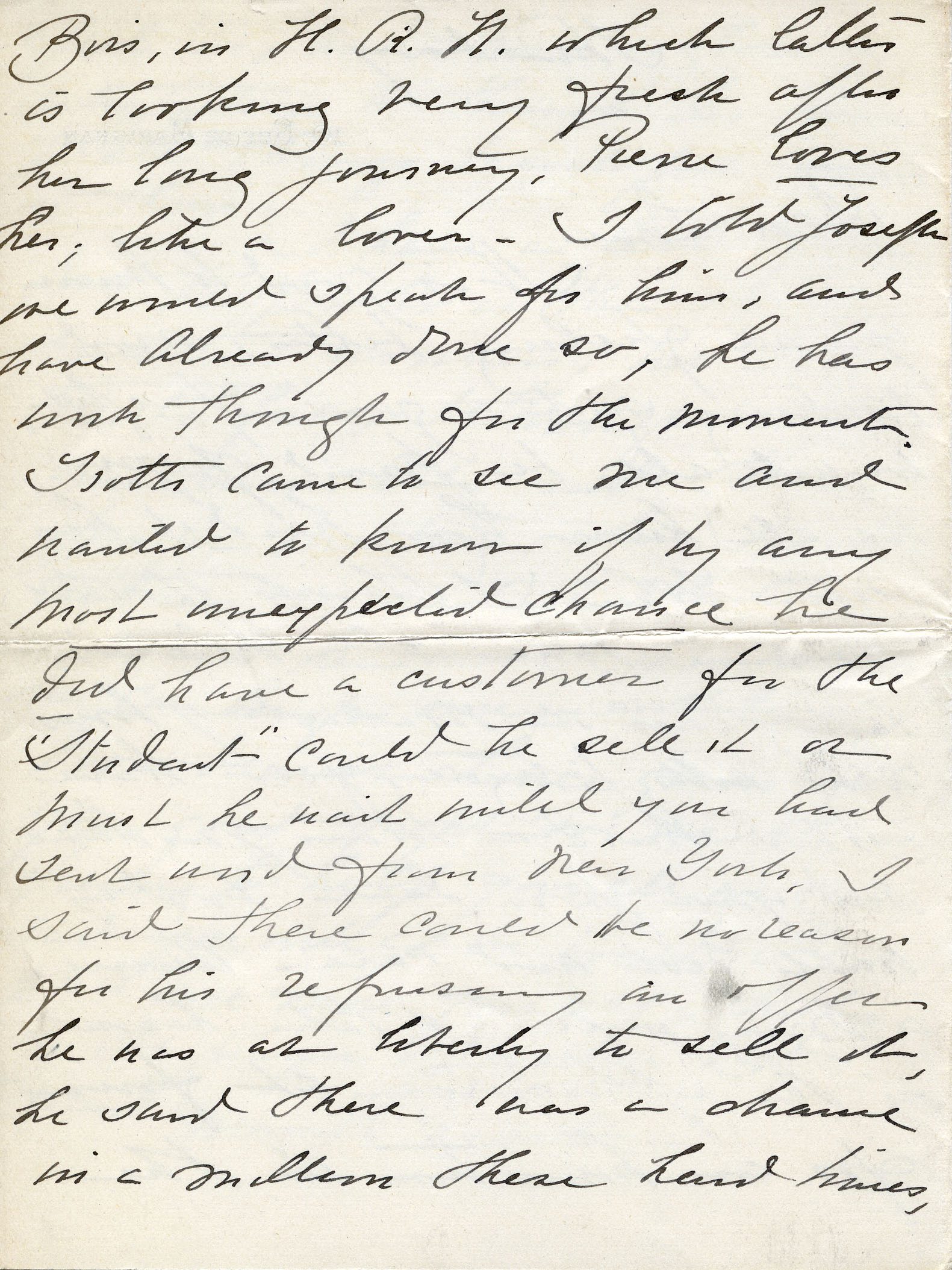

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926)

Letter to Louisine Havemeyer, 1909

Ink on paper, 7 x 5 1/4 in.

Collection of Shelburne Museum Archives, MS439.18

Thursday [1909]

10, Rue de Marignon

Dear Louie

It is good to know you are feeling better, and making such a good fight, we will all be proud of you, we all know how hard it has been." content="When I think of what you have done all these last years it makes my bones ache with fatigue, few have worked harder than you have, and your poor dear body wants rest and care. Annie is doing well. I take her out in the afternoon at four for an hours turn in the Bois, in H. R. H. which latter is looking very fresh after her long journey. Pierre loves her, like a lover. I told Joseph we would speak for him, and have already done so, he has work though for the moment. Trotti came to see me and wanted to know if by any most unexpected chance he did have a customer for the “Student” could he sell it or must he wait until you had sent word from New York. I said there could be no reason for his refusing an offer he was at liberty to sell it, he said there was a chance in a million these hard times, but he wanted that chance, so I accepted for you. Harmisch has written, had already written to Mr Howard Havemeyer! about the Goya’s the asking price was just what I said it would be, 500.000 frs for the whole 50.000 for the Queen on horseback, which Harmisch calls the Velasquez! I hope you also enjoyed your day at Bruges and Ghent. You must have felt pleasure in Electra’s pleasure, ah! my dear you have that before you to see the children develope on the lines their Father would have wished, what a comfort is there. I too feel it, and have a glow of satisfaction to think his love of all things beautiful continues in them.

I have a letter from Mrs. Hoff who is the most persistent woman, but I too can be firm. I thought of your cousin Ella and the prayer meeting, when I read certain so contented sentences relative to her “work”, it is well one can laugh once in a while.

Now dearest Louie go on with your good fight we are all trying to help you all we can and you will get on board the 29th once more yourself. Such is the prayer of your old friend

Mary Cassatt

Unidentified photographer

Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer and Henry Osborne Havemeyer in Paris, date unknown

Gelatin silver print, 8 x 10 in.

Collection of Shelburne Museum Archives, PS3.1-12

On August 22, 1883, Mrs. Havemeyer married businessperson Henry Osborne Havemeyer, sugar refinery owner and founder of the American Sugar Refining Company, who shared a deep love for each other and passion for art. Just as Mrs. Havemeyer entered their relationship with a small art collection, Mr. Havemeyer came into the marriage with a sizable collection of his own and a developed eye for fine and decorative arts, particularly ancient Chinese and Japanese decorative objects and paintings by Dutch and Flemish masters, the French Barbizon school, and American landscape painters. Initially taking the lead in their collecting, Mr. Havemeyer began adding large collections of far-eastern objects such as Chinese porcelains, bronze pots, and rugs, Japanese textiles and tea jars to their new Manhattan brownstone house. While Mrs. Havemeyer quickly grew to appreciate these objects and non-western art, she waited patiently to introduce him to her passion for French avant garde.

In 1889, during the Havemeyers’ first European trip together abroad, Mr. Havemeyer and Cassatt finally met, paving the way for the artist to redirect their collecting habits. While Mr. Havemeyer was initially slow to appreciate French modern art, by the mid-1890s he was making up for lost time. Aided by Cassatt and art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922), the Havemeyers would become the most active art collectors of modern French art in America. Their meeting “resulted in a friendship which lasted through life” according to Mrs. Havemeyer, and respectively, Cassatt would go on to say that “[Mr. Havemeyer] learned with leaps and bounds; there will never be another collector like him.” Working well together, and combining their individual preferences, Cassatt and the Havemeyers—with the invaluable assistance of Durand-Ruel—built an art collection that remains unmatched in its prestige, range, size, and impressions.

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926)

Louisine Havemeyer and her Daughter Electra, 1895

Pastel on wove paper, 24 x 30 1/2 in.

Museum purchase, 1996-46

Cassatt’s commitment to art advising and supporting her artist friends came second to her own artistic practice. Five years after Mrs. Havemeyer and Cassatt’s initial meeting in 1874, Mrs. Havemeyer acquired her first artwork by her dear friend, one of only two known self-portraits by the artist, which now resides in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Following this purchase, Mrs. Havemeyer, and her husband would eventually acquire over a dozen Cassatt works.

In 1895, the Havemeyer family—including their three children, Adaline, Horace, and Electra—spent the summer traveling throughout Europe, accompanying Mr. Havemeyer on a business trip. While in Europe they purchased works ranging from the Renaissance to the contemporary. No doubt, one of their most prized artworks acquired during this summer was a pastel portrait of Mrs. Havemeyer and her youngest daughter, Electra, aged seven. While in France, Mrs. Havemeyer and her children spent time with Cassatt, where the artist completed a rarely accepted portrait commission for her dear friend. In this drawing, Cassatt captures the mother and daughter fashionably dressed, absorbed in comfortable thought, and composed in a relaxed yet unifying position, portraying their close bond.

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926)

Louisine Havemeyer, 1896

Pastel on wove paper, mounted on canvas, 28 3/4 x 23 1/2 in.

Gift of J. Watson Webb, Jr., 1973-94.2

Drawn the year after Cassatt completed the double portrait pastel Louisine Havemeyer and her Daughter Electra, Mrs. Havemeyer returned to the artist and posed for a stunning individual portrait. Dressed in a fashionable white evening gown, Mrs. Havemeyer appears regal and confident, holding a fan. The portrait captures Cassatt’s admiration and respect for her patron and friend. Reciprocally, Mrs. Havemeyer looked fondly back on their relationship saying, “It is difficult to express all that our companionship meant. It was at once friendly, intellectual, and artistic, and from the time we first met Miss Cassatt she was our counsellor and our guide.”

Their relationship thrived not only in shared enthusiasm for art, but also shared interests in other topics such as fashion, civil rights, and political causes. In addition to advising Mrs. Havemeyer on art, Cassatt, a staunch suffragist, pressed Mrs. Havemeyer to become active in the women’s rights movement. Following Mr. Havemeyer’s death in 1907, and with Cassatt’s support and encouragement, Mrs. Havemeyer became active in the organized suffrage movement and mounted two exhibitions benefitting the cause, which featured multiple works by Cassatt.

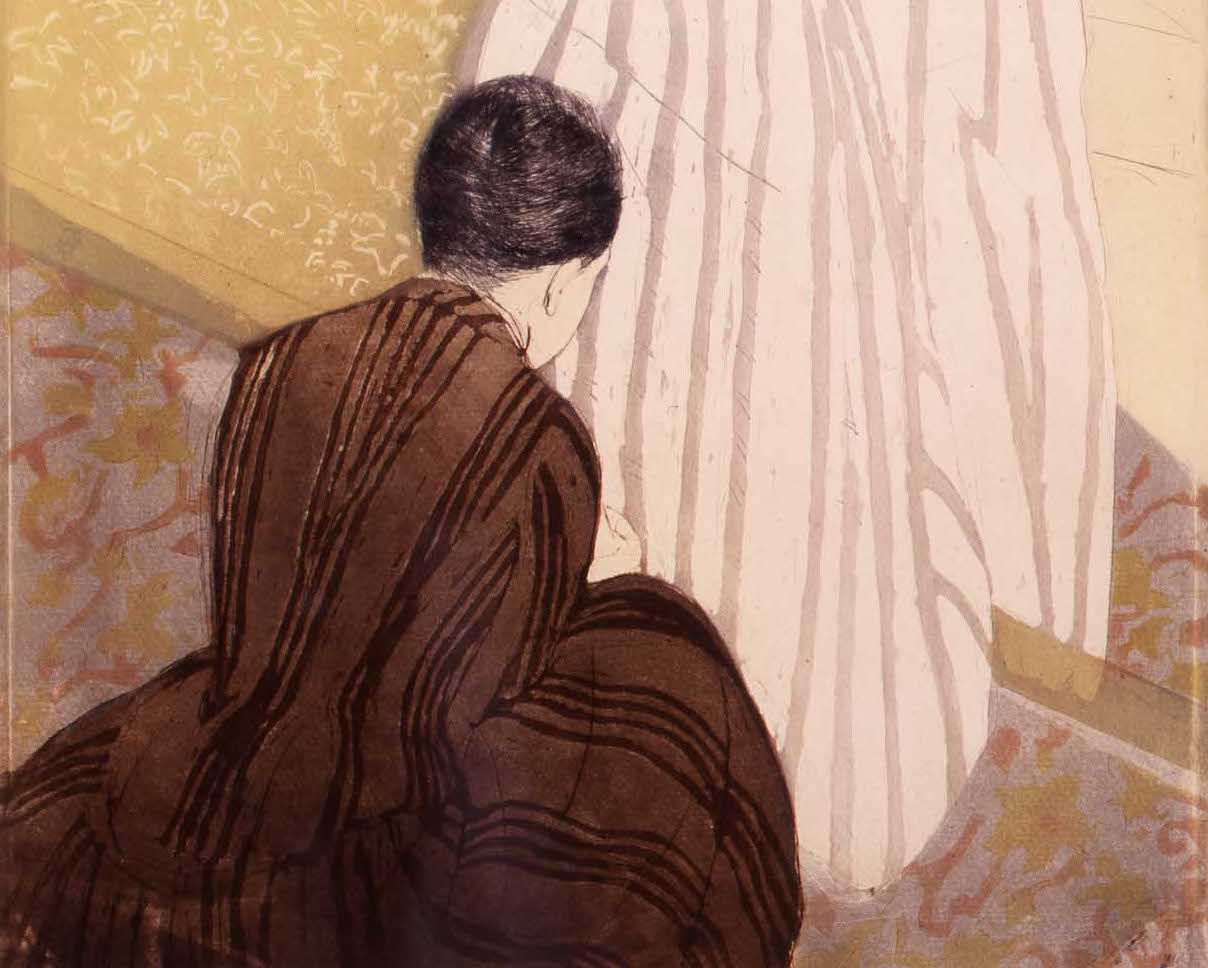

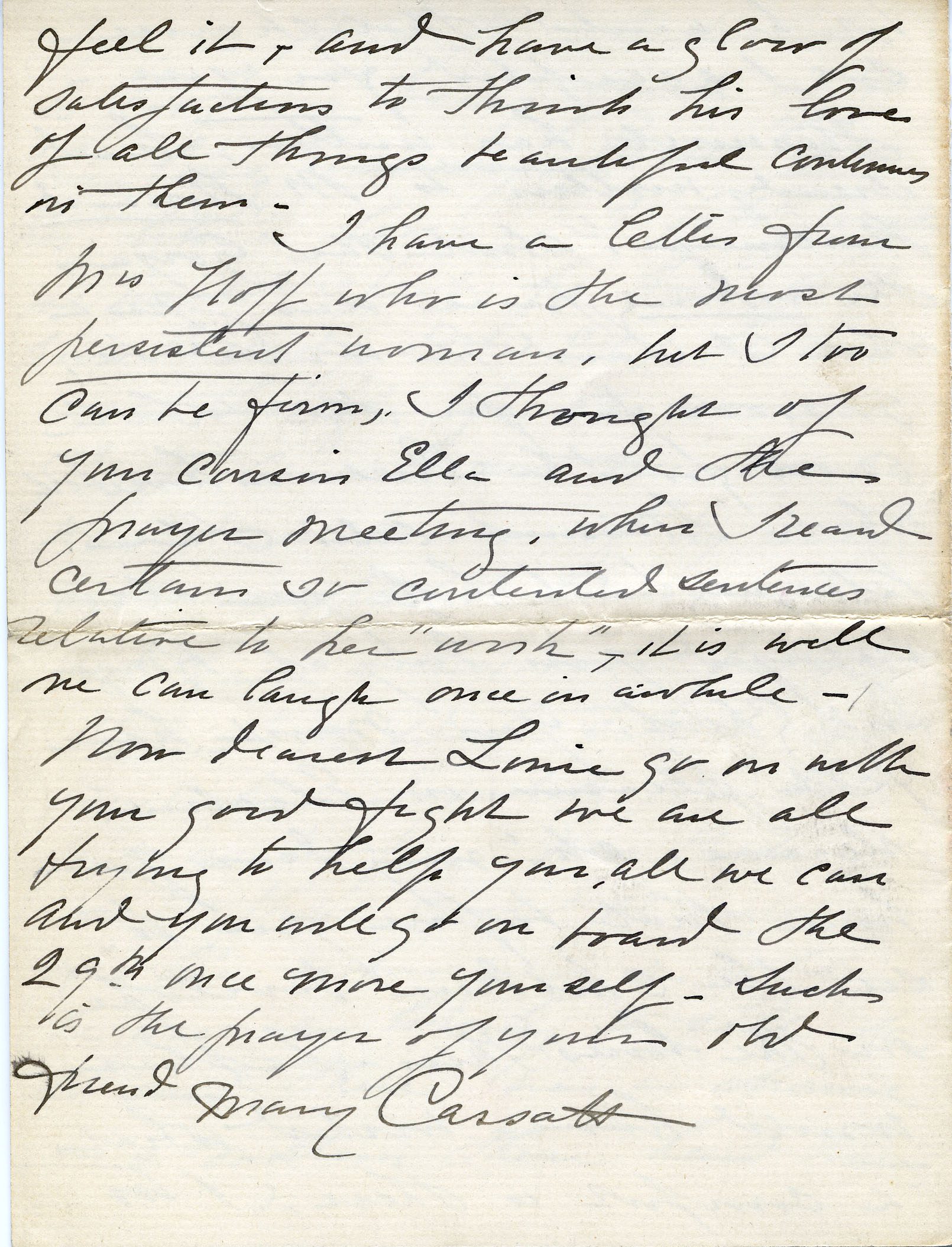

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926)

The Coiffure, 1890-91

Drypoint and aquatint, 17 1/16 x 11 7/8 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.44

In 1891, as the Havemeyers were settling into their new Manhattan house decorated by celebrated designer Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933) and Samuel Colman (1832-1920), Cassatt was abroad, searching for future acquisitions to adorn her friends’ home. She also became absorbed and inspired by Japanese woodblock print techniques and studies. When the artist first encountered the prints on view at Paris’s École des beaux-arts, she enthusiastically reached out to friend and fellow artist Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), writing: “Seriously, you must not miss that. You who want to make color prints, you couldn’t dream of anything more beautiful. I dream of it myself and don’t think of anything else but color on copper…P.S. You must see the Japanese—come as soon as you can.” Taken with traditional Japanese elements observed in these prints—bold outlines, decorative patterns, saturated colors, and complex compositions—Cassatt began a yearlong experiment creating a series of 10 colored aquatints inspired by this style.

The Coiffure and The Fitting demonstrate Cassatt’s knowledge and expertise of a challenging medium and technique and her understanding of the basic aesthetic elements of traditional Japanese prints. In April 1891, her prints were featured in her solo exhibition at Durand-Ruel’s Paris gallery. Later that same year, the Havemeyers purchased her complete set of aquatints, including these two prints, for their new home.

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926)

The Fitting, 1890-91

Drypoint and aquatint, 19 x 12 1/2 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.45

Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (French, 1796-1875)

Greek Girl, Mlle. Dobigny, 1868-70

Oil on canvas, 33 3/16 x 21 3/4 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.10

Over a single day, September 19, 1895, the Havemeyers purchased eleven paintings from the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris. Of the nearly dozen artworks acquired—six by Degas, a Daumier, a Millet, a Courbet, and a Manet—they added this Corot painting to their growing collection, which would eventually consist of over 20 works by the renowned artist. While Cassatt did not advise the Havemeyers to pursue this particular painting, she was well aware of, and admired, the work of Corot, and most importantly, guided the collectors to Paul Durand-Ruel, the pioneering Impressionist and Barbizon school art dealer. Cassatt expressed confidence in and support of her dealer Durand-Ruel, enthusiastic of his successes, such as his expansion of his Paris gallery to New York City. Throughout the years, Cassatt was always due at least partial credit for his sales.

Over a single day, September 19, 1895, the Havemeyers purchased eleven paintings from the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris. Of the nearly dozen artworks acquired—six by Degas, a Daumier, a Millet, a Courbet, and a Manet—they added this Corot painting to their growing collection, which would eventually consist of over 20 works by the renowned artist. While Cassatt did not advise the Havemeyers to pursue this particular painting, she was well aware of, and admired, the work of Corot, and most importantly, guided the collectors to Paul Durand-Ruel, the pioneering Impressionist and Barbizon school art dealer. Cassatt expressed confidence in and support of her dealer Durand-Ruel, enthusiastic of his successes, such as his expansion of his Paris gallery to New York City. Throughout the years, Cassatt was always due at least partial credit for his sales.

The Greek Girl features one of the artist’s favorite models, Emma Dobigny, who also posed for Portrait of Mlle. Dobigny. Corot used her as a recurring subject because of her chameleon-like versatility and liveliness; “It's just that changeability that I love in her,” he once said. “My object is to express life.” She could embody the subject of a pensive Greek woman—as seen in this painting, donning an elegantly embroidered Greek coatdress over a chemise—or appear more demure and passive, as in Portrait of Mlle. Dobigny. Corot’s evolving interest in dressing his models in non-Western or exotic costumes would have appealed to the Havemeyers’ taste for Eastern style and design—influences echoed in their Manhattan house’s interior design.

Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (French, 1796-1875)

Portrait of Mlle Dobigny, 1868-70

Oil on wood, 30 3/4 x 18 1/2 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.11

Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (French, 1796-1875)

La Bacchante à la panthère (The Golden Age), 1855-60

Oil on canvas, 21 1/2 x 37 1/2 in.

Anonymous gift in memory of Harry Payne Bingham, 1993-30

Following Cassatt’s taste and counsel, in 1897, Mr. Havemeyer played the role of art advisor for his friend, Colonel Oliver Hazard Payne (1839-1917), a businessperson affiliated with the oil, steel, and tobacco industries and created several trusts. Payne long expressed appreciation for the Havemeyer’s collection; in her autobiography, Mrs. Havemeyer recounted: “It was during the pleasant evenings we spent together in the early years of our acquaintances that I think the Colonel began to take an interest in pictures. Often Mr. Havemeyer would suggest a fine picture to him or even let him have one he [himself] had intended to buy, and I have frequently heard Colonel Payne say that he owed many of his finest canvases to Mr. Havemeyer’s advice and generosity.” One of the paintings Mr. Havemeyer scouted and secured for Payne was Corot’s La Bacchante à la panthère (The Golden Age), despite competition with another interested client of Durand-Ruel's. A year later, in 1898, Mr. Havemeyer and Durand-Ruel enticed Payne to Impressionist art, perhaps with Cassatt’s council, using a page from her advisory playbook and presenting him with a Degas ballet scene.

La Bacchante à la panthère (The Golden Age) was beloved by Payne and remains one of the artist’s more unique figure scenes. The reclining nude, in the tradition of classical 16th and 17th century female nudes, appears to be Diana—the Roman goddess of the hunt—identified by her bow. However, there is also reference to Bacchus—Roman god of agriculture, fertility, and wine—in both its title and the inclusion of the infant god riding a panther, which traditionally pulls the older Bacchus in his chariot.

Gustave Courbet (French, 1819-77)

Still Life: Fruit, 1871

Oil on canvas, 22 x 28 1/2 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.12

Just as the Havemeyers’ taste in art extended beyond Impressionism, Cassatt was also taken with Realist and Old Master artists. In fact, during Cassatt and Mrs. Havemeyer’s initial meeting in 1874, the artist abruptly left to attend a viewing of Gustave Courbet’s recently completed painting at his studio. Cassatt shared her zeal for Courbet with Mrs. Havemeyer, and the Havemeyers quickly returned her enthusiasm for his work. “As usual, I owe it to Miss Cassatt that I was able to see the Courbets,” Mrs. Havemeyer wrote in her memoirs. “She [Cassatt] took me there, explained Courbet to me, spoke of the great painter in her flowing generous way, called my attention to his marvelous execution, to his color, above all to his realism, to that poignant, palpitating medium of truth through which he sought expression. I listened to her with such attention as well stood before his pictures and I never forgot it.” Mr. Havemeyer also grew to be one of Courbet’s biggest supporters, with Mrs. Havemeyer writing: “It did not take Mr. Havemeyer long to recognize Courbet as a great painter. When we visited the exhibition, One Hundred Masterpieces, in Paris in 1900, he stood before Courbet’s Les Cesseurs de Pierres as if rooted to the spot.”

While Mrs. Havemeyer was entranced with Courbet’s female nude paintings—and would eventually acquire several—in addition to several Courbet landscapes, this still life painting shares many of the formal qualities Mrs. Havemeyer loved about the artist’s rendering of the female form. Still Life: Fruit, which Mrs. Havemeyer purchased in 1921 following the death of her husband, celebrates the flesh and beautiful imperfections of the aging fruit.

Still Life: Fruit originally slipped through Mrs. Havemeyer’s fingers as the under-bidder at a December 13, 1912 auction in Brussels. She was desperately searching for an attractive fruit still life painting by the artist to round out her collection. Following another failed attempt at purchasing this painting due to its escalating price, she would later acquire Still Life: Fruit for considerably more money 8 years later.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Repetition au foyer (Rehearsal in the Studio), ca. 1875

Tempura on canvas, 17 1/4 x 23 in.

Gift of Electra Webb Bostwick, 1976-78

In 1877, at 22 years old, Mrs. Havemeyer pulled together her allowance—along with some borrowed money from her sisters—to purchase her first major artwork, a pastel drawing by Edgar Degas that cost 500 francs or 100 dollars, forever shaping the future of her taste and art collection. This acquisition of Degas’s Repetition de ballet—which today resides at Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art—marked not only Degas’s first sale to an American art patron but also Cassatt’s first step as councilor as an art advisor. Cassatt’s own deep admiration for Degas came on fast, as it was just earlier that year that she first meet Degas and was invited to exhibit her work with the Impressionists. Cassatt convinced Mrs. Havemeyer to make this purchase by inviting her to a window display featuring the Degas’s pastels and compellingly spoke in admiration about his work and its worth. Initially, Mrs. Havemeyer admitted that she found Degas’s work to be “so new and strange to me! I scarcely knew how to appreciate it, or whether I liked it or not.” Trusting Cassatt’s guidance and taste she purchased the work. In recognition of Cassatt’s influence, she reminisced in her memoir: “I believed it takes special brain cells to understand Degas. There was nothing the matter with Miss Cassatt’s brain cells, however, and she left me in no doubt as to the desirability of the purchase and I bought it upon her advice.” With Cassatt’s encouragement, and after acquiring one of his pastels, Mrs. Havemeyer became passionate about Degas’s work and those of Cassatt’s inner circle, purchasing paintings by Monet and Pissaro later that year.

Cassatt continued to advise the Havemeyers to acquire numerous other Degas paintings and drawings for their collection. According to Mrs. Havemeyer, “…almost all were bought about the time Degas painted them; many were purchased through Durand-Ruel, and others recommended by Miss Cassatt who watched their execution in the studio or saw them in the various exhibitions.” The Havemeyers also paid Degas several studio visits, during which they heeded the artist’s own recommendations and purchased a few of his works based on his advice.

Sharing formal characteristics to the first painting Mrs. Havemeyer purchased by Degas, Repetition au Foyer (Rehearsal in the Studio) was added to the Havemeyer’s collection on February 17, 1899. This pastel drawing depicts an informal light-filled ballet rehearsal and highlights the athleticism of these professionals.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Le pas sur la scene (Dancer in Green), date unknown

Pastel on wove paper, 28 x 15 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.8

Degas was captivated by the world of ballet, devoting decades of his career to create hundreds of paintings, pastels, drawings, and sculptures capturing the elegance and grace of ballet dancers either backstage at rest, in rehearsal, or performing on stage. To capture the physicality and discipline of the ballerinas, Degas required his models pose for extended lengths of time, enduring agonizing discomfort as they held their difficult positions. Cognizant of Degas’s decades-long fascination with this subject, Mrs. Havemeyer once pressed the artist on why he was drawn to these athletic entertainers, to which he replied ‘Because, Madame, it is all that is left us of the combined movement of the Greeks.”

When advising future promising collectors, Cassatt often used Degas’s ballet scenes to initiate her collectors’ interest in Impressionism, as she did for Mrs. Havemeyer in 1877 with her first acquisition of Repetition de ballet. Yet, as Cassatt wrote to Mrs. Havemeyer in 1913, this artist and style was not for all, but an acquired taste, especially Degas’s female nudes, noting: “Degas’ art, after all, is for the very few…those things are for painters and connoisseurs.”

Later in Degas’s career, by the 1880s, he shifted his attention away from larger group studies of dancers—such as Repetition au Foyer (Rehearsal in the Studio)—and instead focused on single portraits and investigations of color. Le pas sur la scene (Dancer in Green), is a symphonic celebration of green—through incorporation of absinthe light green reflections from the stage lighting and deep forest greens in the painted backdrops—composed in a cropped, vertical composition reminiscent of photography and Japanese prints.

The Havemeyers purchased Le pas sur la scene (Dancer in Green) on September 19, 1895, from the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris. This pastel was one of 11 works they acquired that day from the art dealer.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Deux danseuses (Two Dancers), ca. 1879

Pastel and gouache on paper, 18 1/8 x 26 1/4 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.6

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Cast by A. A. Hébrard et Cie (Paris, France, 19th-20th centuries)

Cheval se cabrant (Rearing Horse), modeled ca. 1888-90, cast 1920

Edition: 4/O

Bronze, 12 1/4 x 10 x 8 1/2 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.24

Following Degas’s passing in 1917, more than 150 figurative sculptures were discovered in the artist’s studio –only one of which had been exhibited publicly. The molds were mostly made of fragile modeling materials of wax and clay, and when discovered, they were in varying degrees of condition and deterioration. While Degas’s sculpted models were not well-known prior to his death, those who had visited his studio, including Cassatt and the Havemeyers, were aware of his sculptures. In her memoirs, Mrs. Havemeyer recounted that “I had an opportunity to look around [Degas’s] apartment. I found a little vitrine containing the model of a horse and the remains of his celebrated statue of La Danseuse [Little Fourteen-Year –Old Dancer].”

Beginning in 1917, Mrs. Havemeyer began writing to Cassatt inquiring about the availability and condition of the figures. In 1920, Degas’s heirs approved bronze copies to be cast from these molds, creating a limited 22 edition series—lettering them A through T—for a total of 72 cast figures. In 1921, Mrs. Havemeyer acquired the first edition—Edition A—of Degas’s bronze sculptures for her collection, which would have included this bronze equine sculpture.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Cast by A. A. Hébrard et Cie (Paris, France, 19th-20th centuries)

Cheval s'enlevant sur l'obstacle (Horse Clearing an Obstacle), modeled ca. 1888-90, cast 1920

Edition: 48/G

Bronze, 9 7/8 x 16 1/4 x 9 1/2 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.25

Following Degas’s passing in 1917, more than 150 figurative sculptures were discovered in the artist’s studio –only one of which had been exhibited publicly. The molds were mostly made of fragile modeling materials of wax and clay, and when discovered, they were in varying degrees of condition and deterioration. While Degas’s sculpted models were not well-known prior to his death, those who had visited his studio, including Cassatt and the Havemeyers, were aware of his sculptures. In her memoirs, Mrs. Havemeyer recounted that “I had an opportunity to look around [Degas’s] apartment. I found a little vitrine containing the model of a horse and the remains of his celebrated statue of La Danseuse [Little Fourteen-Year –Old Dancer].”

Beginning in 1917, Mrs. Havemeyer began writing to Cassatt inquiring about the availability and condition of the figures. In 1920, Degas’s heirs approved bronze copies to be cast from these molds, creating a limited 22 edition series—lettering them A through T—for a total of 72 cast figures. In 1921, Mrs. Havemeyer acquired the first edition—Edition A—of Degas’s bronze sculptures for her collection, which would have included this bronze equine sculpture.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Cast by A. A. Hébrard et Cie (Paris, France, 19th-20th centuries)

Cheval au galop tournant la tete a droit, les pieds ne touchant pas le sol (Horse Galloping, Turning Head to Right, Feet Not Touching the Ground), modeled ca. 1879, cast 1920

Edition: horse 32/G, jockey 36/G

Bronze, 11 x 14 1/4 x 5 1/4 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.22

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Cast by A. A. Hébrard et Cie (Paris, France, 19th-20th centuries)

Cheval au galop sur le pied droit (Horse Galloping on Right Foot, Back Left only Touching the Ground), modeled possibly before 1871, cast 1920

Edition: horse 25/G, jockey 35/G

Bronze, 9 1/2 x 12 3/4 x 7 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.23

Édouard Manet (French, 1832-83)

Le saumon, ca. 1864

Oil on canvas, 29 x 37 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.16

Following their marriage in 1883, one of the first Impressionist paintings the Havemeyers purchased together was Manet’s Le saumon in 1886. Durand-Ruel’s first major traveling Impressionist exhibition for the American art market was “The Impressionists of Paris,” which featured select private loan artworks—including Mrs. Havemeyer’s Monet’s Le pont, Amsterdam—and new paintings for sale. While Durand-Ruel’s first Parisian exhibition of Impressionist art in 1876 did not receive positive reviews, one reporter referring to it as an “insane asylum,” his exportation of Impressionism in America received warm praise.

Enthusiastic about the exhibition, Mrs. Havemeyer asked her husband to purchase her a painting by Manet from the show, should he see one he found favorable during his visit to Durand-Ruel’s gallery. Accompanied by American artist Samuel Colman, Mr. Havemeyer later reported to his wife: “I saw the exhibition this morning. There were two Manets in it, one of a boy with a sword and the other a still life [Le saumon]. The still life was very fine and I bought it for you, but I must confess that the Boy with the Sword was too much for me.”

Édouard Manet (French, 1832-83)

Au jardin, 1870

Oil on canvas, 17 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.

Gift of Dunbar W. and Electra Webb Bostwick, 1981-82

Cassatt was fond of much of Manet’s oeuvre, but she favored the artist’s female subjects,—particularly those done in half-length—his striking marine paintings, and his Spanish subjects. The latter draws parallel to Cassatt’s own interest in Spanish art and artists—particularly the art by El Greco (1541-1614) and Francisco Goya (1746-1828)—both of whom she would tout to her clients, such as the Havemeyers, for their collections.

Au jardin is not one of the artist’s more exotic paintings, but rather depicts an intimate and familiar scene of a family lounging in a Parisian garden. Au jardin was one of Manet’s first en plein-air paintings (painting outdoors), displaying his ability to transpose the ephemeral effects and nuances of moving light and color. Strategically bathing his sitters in light and shadow, the painting epitomizes characteristics both Cassatt and the Havemeyers admired of the artist. Mrs. Havemeyer treasured the quiet familial scene, calling it “a picture full of charm and sentiment, of home life and refinement, executed with admirable skill and showing Manet's mastery of light and shade.”

Édouard Manet (French, 1832-83)

The Grand Canal, Venice, 1875

Oil on canvas, 23 1/8 x 28 1/8 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.15

Following the opening of his first permanent gallery in New York City, Durand-Ruel organized a Manet solo exhibition and, once again, the Havemeyers proved to be instrumental to the gallery’s success as both lenders and buyers. The collectors agreed to lend Durand Ruel Le saumon and purchased a painting many critiques believed to be the crown jewel of the exhibition, Le Grand Canal a Venise. Cassatt swiftly gave the Havemeyers her blessing, strongly believing that this painting would be a thoughtful addition to their collection. In her memoirs, Mrs. Havemeyer recalled that Cassatt “congratulated us when we bought this picture saying she considered it one of Manet’s most brilliant works; it was so full of light and atmosphere and expressed the very soul and spirit of Venice.”

Manet created this vibrant painting during the fall of 1875 while visiting the popular Italian city. During the artist’s month-long sojourn, he became discouraged in his attempts to capture the canal-city to his satisfaction. On his last afternoon there, Manet painted en plein-air, capturing a classically Venetian subject, a gondolier navigating his vessel across the Grand Canal. Mrs. Havemeyer recalls a letter Cassatt wrote her sharing that “[Manet] told me he was so pleased with the result of his afternoon’s work that he decided to remain over a day and finish it. My dear,’ concluded Miss Cassatt, ‘that is the way Manet happened to paint your Venice.”

Édouard Manet (French, 1832-83)

Polichinelle, 1874

Lithograph, 20 5/16 x 13 5/8 in.

Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.43

This color lithograph was one of the more controversial and political works of art in the Havemeyer collection. Neither Cassatt nor the Havemeyers shied away from expressing political beliefs. For instance, Cassatt and Mrs. Havemeyer both supported American women’s suffrage and the 19th Amendment; Cassatt wrote to Mrs. Havemeyer after Mr. Havemeyer’s death encouraging her to advocate for women’s rights and to “go in for [suffrage].”

Following the success of his watercolor rendition of Polichinelle, exhibited at the 1874 Salon, Manet began creating a series of this lithograph for political journals. The artist was proud of this print, representative of his mastery and technical skill of this medium. Posed by Manet’s friend, artist Edmond André (1837-1877), the clownish military figure is wearing an operatic costume of the Italian theater character Polichinelle, commonly played as a comedic drunk. Evidently, in 1874, Manet’s figure was perceived to be a caricature of General Patrice de MacMahon (1808-1893), who would be elected President of the French Republic in 1875. The general had recently authorized brutal treatment of public protestors, and so Manet’s presumed comparison between Patrice de MacMahon and theatrical character was not that farfetched. Unfortunately, the government censored and halted the print’s production due to this supposed caricature.

The lines included at the bottom of the print, written by poet Theodore de Banville (1823-1891), roughly translate to:

“Fearsomely pink, eyes glinting with the glare of Hell,

Brazen and drunk—divine—that’s him, Polichinelle.”

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Le pont, Amsterdam (The Drawbridge, Amsterdam), 1870-71

Oil on canvas, 21 x 25 in.

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.5

In 1877, subsequent to her first art purchase of a Degas pastel, Cassatt directed the perceptive Mrs. Havemeyer to acquire her first painting by Monet, Le pont, Amsterdam, for 300 francs. She became Monet’s first American art patron—as she had for Degas— and Le pont, Amsterdam is celebrated as the first Impressionist painting to make the voyage across the Atlantic. Mrs. Havemeyer would not acquire another painting by Monet until 1894, when she and her husband began collecting moderns in earnest.

For an artist fascinated with the effects of color and light, the waterways of Holland were an appropriate location for Monet to work. On one of his many visits to Amsterdam—around the time of the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris on April 15, 1874—the artist painted this city landscape depicting notable architecture and landmarks—such as Montelbaanstoren, the historic watchtower—focusing on the rising Peperbrug drawbridge over the Rapenburgwal canal. Utilizing bold colors and short brushstrokes, Monet captures the rainy atmosphere and the shifting effects of light on the active scene.

Monet’s early work and his seascapes were obviously favorites of the Havemeyers, but their advisor, Cassatt, also preferred them. Cassatt was not, however, a supporter of Monet’s later work; in 1918 she mockingly wrote that Monet’s waterlilies “look to me like glorified wallpaper.”

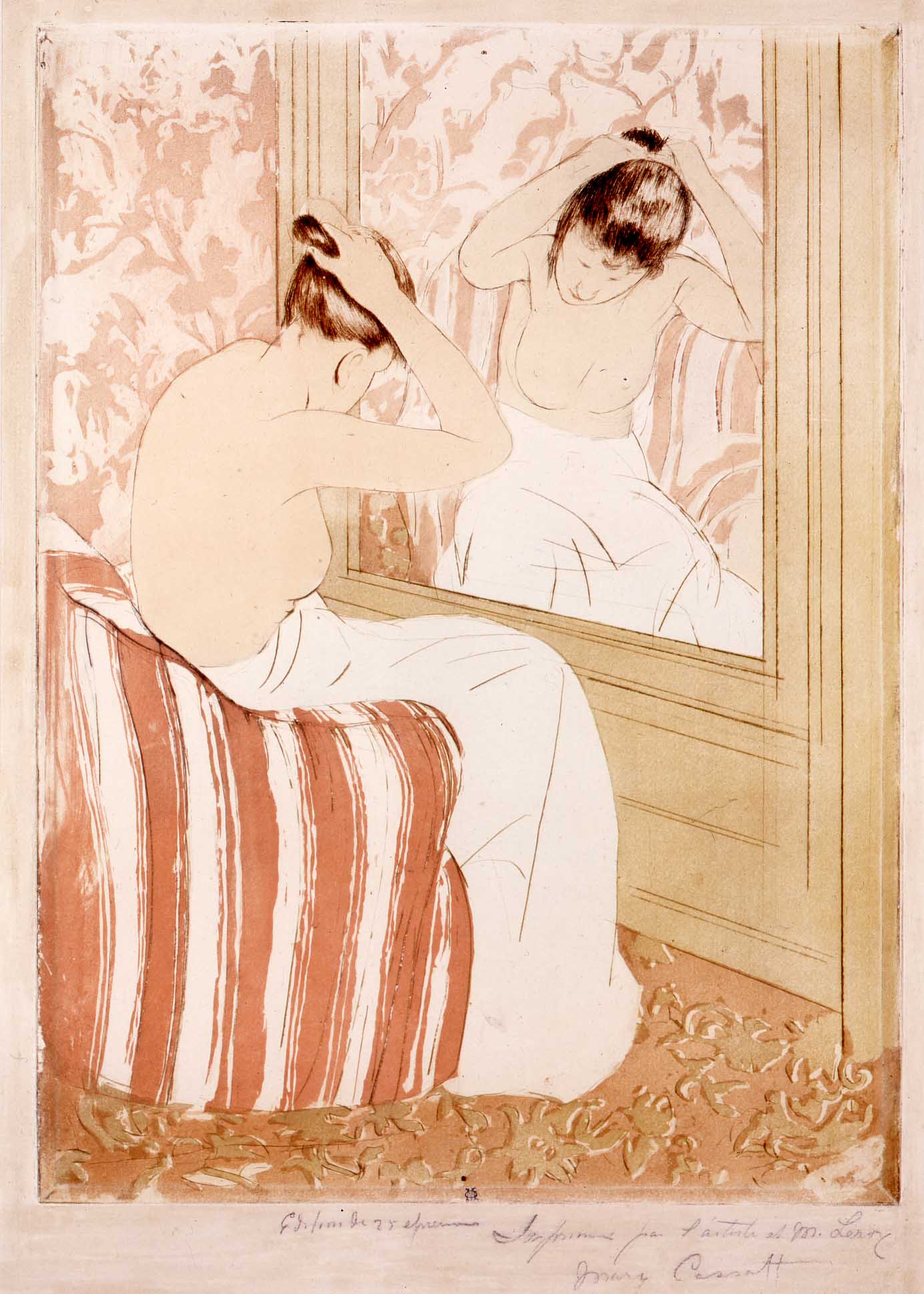

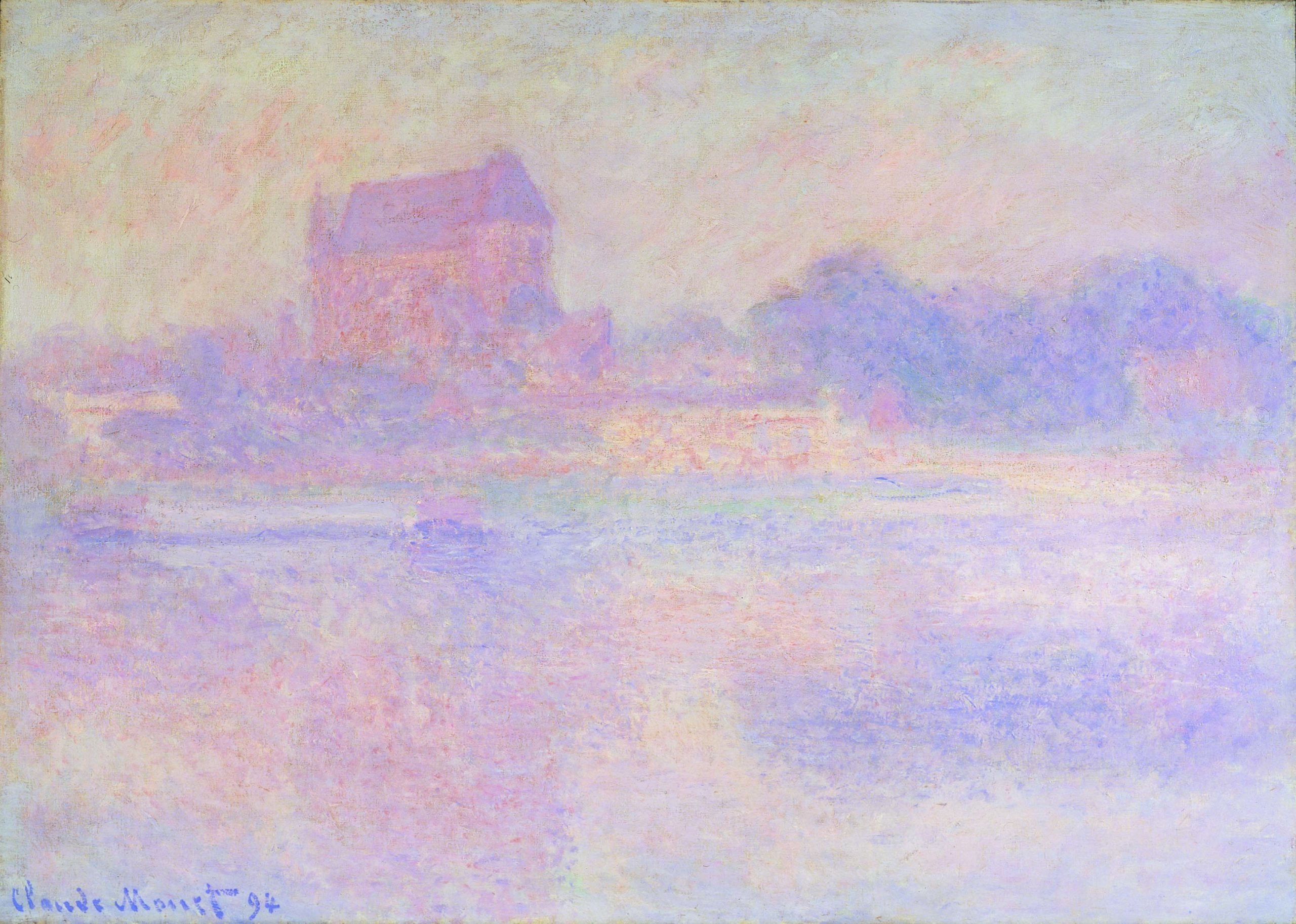

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

L'Église de Vernon, brouillard (Old Church of Vernon), 1894

Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 35 1/2 in.

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.4

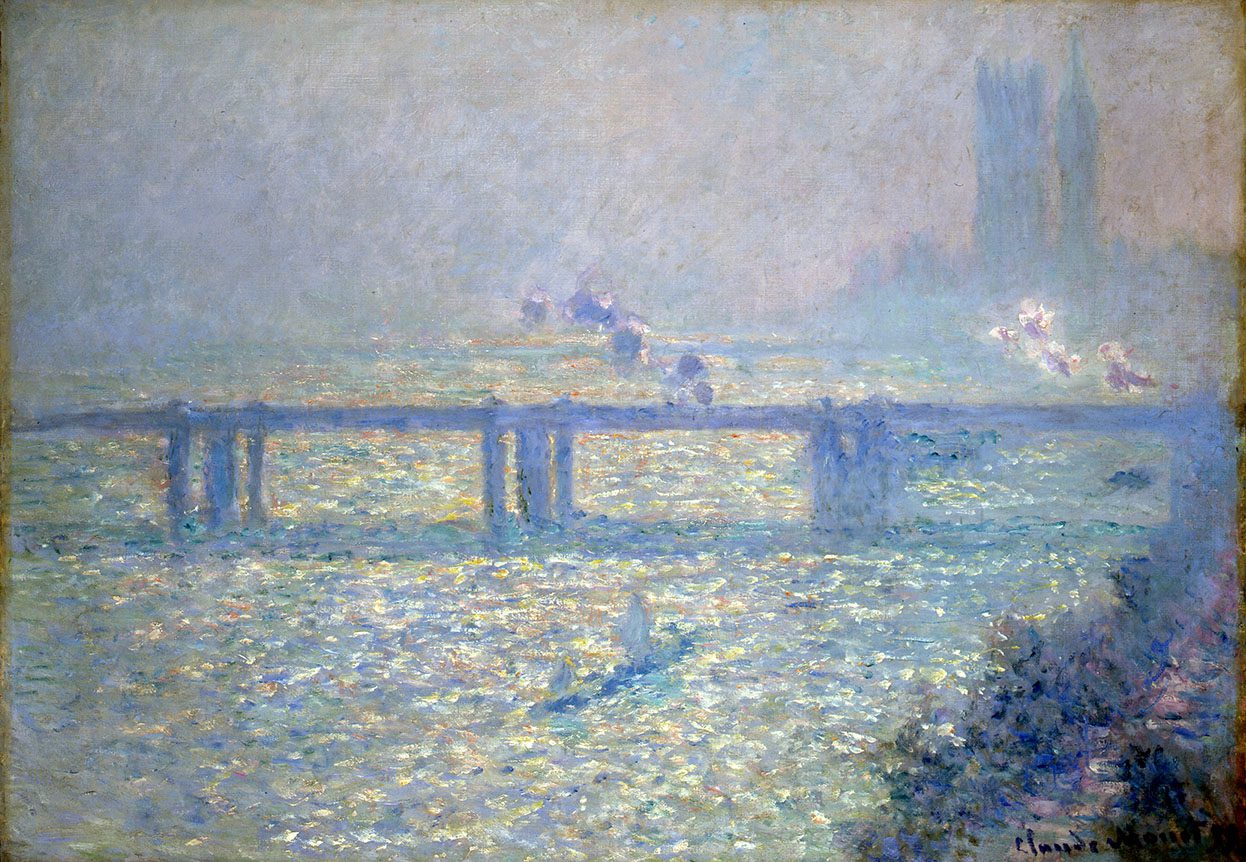

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

The Thames at Charing Cross Bridge, London, 1899

Oil on canvas, 25 x 35 3/8 in.

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.3

Cassatt considered and promoted the investment potential of art to her financially savvy clients—such as her own brother, railroad industrialist Alexander Cassatt (1839-1906)—and this would have no doubt appealed to businessperson Mr. Havemeyer as well. However, both the Havemeyers and Cassatt were more concerned with their own taste and the lasting legacy of these artworks, and the Havemeyers confidently acquired new paintings by modern artists, like Monet. They purchased The Thames at Charing Cross Bridge, London not long after its paint had dried. The Havemeyers were so assured of Monet’s talent and reputation that they were among the first collectors to acquire his Thames scenes, even before the 1904 major exhibition of his London works.

Capturing the heavy, fog-laden atmosphere of London in the fall, Monet integrates color, line, and light to create a balanced composition that expresses the spontaneity of a fleeting moment in time. Monet traveled to the English capitol in the fall of 1899 to paint this new Thames series, portraying a steam engine roaring across the Charing Cross Bridge and boats beneath it, all intentional symbols of modernity and prosperity.

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Meules, effet de neige (Grainstacks, Snow Effect), 1891

Oil on canvas, 23 x 39 in.

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.1

In January 1895, Durand-Ruel’s New York City gallery featured a forty-year retrospective exhibition of Monet’s landscapes. The exhibition received rave reviews. A New York Times critique, acknowledging Monet’s artistic influence, wrote: “There is scarce an exhibition in the last few years but shows in a dozen or more pictures his directing agency; from the greatest of his contemporaries to the humblest student in the schools, there are who have hesitated to take from him some hint or suggestion.” Once again, the Havemeyers were ready to support Durand-Ruel and his exhibition, lending and purchasing artworks. Within the first month of the opening, the Havemeyers purchased Meules, effet de neige from the gallery. Previously, American industrialist Alfred Pope (1842-1913), who also sought the council of Cassatt, owned the winter landscape painting.

Meules, effet de neige is a symphonic study of Impressionist interests of color and light through close inspection of grain stacks in a field in Giverny. This painting is one of over two dozen canvases Monet created in a series studying these stacks near his home in varying weather, time of day, and light. Meules, effet de neige is bathed in soft hues of blues, purples and grays, recalling the overcast and atmospheric winter season. American art critic, Frank Jewtt Mather Jr. fittingly referred to one of Monet’s similar grain stack painting as “simply made for a Museum.” There is little doubt that the Havemeyers and Cassatt would have concurred with such a statement and would be pleased that today it resides at Shelburne Museum.

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Les glaçons, (The Ice Floes), 1880

Oil on canvas, 38 1/4 x 58 1/4 in.

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc., 1972-69.2