What are the myths that bind Americans as a people? Where do we find opportunities to come together? How do we commemorate events, from the meaningful to the mundane, in our public lives? And finally, how do we understand objects that shape the ways we move through our world?

American Stories: Community explores the ways Americans celebrate the bonds of friendship, family, and civic identity through remarkable and unexpected objects drawn from Shelburne Museum’s permanent collection. Iconic paintings like Edward Hicks’ Penn’s Treaty with the Indians invite opportunities for reevaluating the ways we understand national, foundational myths. A meeting house, general store, and hotel offer perspectives on the places we come together in daily life, both for celebration, intellectual edification, and sustenance. Amish, Mennonite, and Quaker bedcovers, including an extraordinary, inscribed “signature” or “friendship” album quilt made by the family and friends of Eliza and John Noble, commemorate the ways that many hands bring comfort and remind us of our roots. A humble seed box and a celebrated hooked rug remind us that we can provide sustenance for our communities, even in difficult times.

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by The Donna and Marvin Schwartz Foundation and the Barnstormers at Shelburne Museum.

Edward Hicks (American, 1780-1849)

Penn's Treaty with the Indians, 1840-45

Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 ¼ in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Edith Halpert, The Downtown Gallery, 1953-1179

The story of William Penn’s treaty with the Indians at Shackamaxon, Pennsylvania in the early 1680s is one of America’s foundational historical myths. In Edward Hicks’ version of the story, William Penn stands at the center of the composition with arms outstretched in a gesture of embracing friendship. Several of his Quaker compatriots offer bolts of fabric to the Lenni Lenape people grouped on the left side of the canvas. A large tree—the so-called “Treaty Elm”—arches over the group. An inscription at the bottom of the canvas dates the scene to 1681 and notes that Penn’s oath was “never broken” and is the “foundation of religious and civil liberty” in the United States.

Despite this romanticized vision of intercultural relations, the realities of Quaker and European colonial relations with Native Americans were not as simplistic as painted visions of Penn’s Treaty with the Indians would have had viewers believe. In fact, scant evidence exists that a written treaty ever existed. Some scholars have argued that the scene may be an aggregation of memories of many documented treaties or land purchases. Others have posited that the tradition was invented to align with Quaker ideals of peaceful and fair compromise and idealize Pennsylvania’s colonial past.

Unidentified maker

Charles Banner Trade Sign, 1806

Carved, turned and painted wood, 50 ¼ x 30 ¾ x 2 3/8 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Israel Sack, Inc., 1954-15

Most popular in North America from the late 17th to the mid-19th centuries tavern signs are typically two-sided, wooden signboards painted on both sides with a combination of words and images and usually equipped with decorative, forged-iron hanging hardware. While little is known about this sign’s origins, its form, inscriptions, and iconography suggest that it may have been created as an advertisement for an early 19th-century “public house,” a dwelling licensed to provide food and lodging for travelers. Interestingly, tavern signs like these often employed images—rather than written words—to communicate with potential patrons, an important advertising function when a significant portion of a business’s clientele may not have been literate.

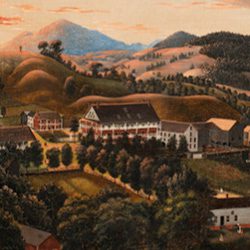

James Hope (American, b. Scotland, 1818-92)

Clarendon Springs, Vermont, 1853

Oil on canvas, 26 1/8 x 36 3/16 in.

Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1957-690.10

Born in Scotland and raised in Canada, James Hope settled in Vermont in the 1830s and established a studio in West Rutland by 1843. In early landscapes like this one, Hope used his sharp eye for detail to depict idealized views of New England. In this bird’s-eye view of Clarendon Springs, Vermont, a popular 19th-century health resort, Hope rendered buildings such as the Clarendon Springs Hotel—the large brick building with wraparound porches in the center of the composition—in striking detail and perspective. The busy resort center, populated with people, wood-frame buildings, roads, and bridges along the banks of the Clarendon River, stands illuminated by the glowing, sunset-drenched western sky.

Unidentified maker

A. Tuckaway General Store, 1840

re-erected, 1953-54

Gift of Suzanne B. Smith, 1952-1067

Just as a real general store would have been the center of its community, Shelburne Museum’s General Store is at the center of the Museum’s campus. Visitors can browse shelves and cabinets full of late 19th-century essentials and explore adjoining rooms that include a post office, barber shop, and tap room. Medical equipment, tools, and furnishings from the early 20th century are on view upstairs.

The General Store was built as the post office for the town of Shelburne in 1840. Outstanding architectural features include its Greek Revival, front-gable orientation, emphasized by a multi-paned triangular window above the second story. The building was moved intact to the Museum in 1952.

The adjacent Apothecary Shop was built at the Museum in 1959 to recreate a late 19th-century druggist’s shop. Display shelves, a pill press, and other professional tools are all on view, while the main room displays both patent medicines, and herbal remedies from an earlier period. The compounding room—where medicines would have been prepared—has a brick hearth, copper distilleries, and percolators.

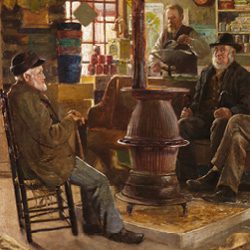

Abbott Fuller Graves (American, 1859-1936)

A New England Country Grocery, 1897

Oil on canvas, 36 x 42 in.

Donated by the Harper Family Foundation in honor of its Founders, Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Harper, Omaha, Nebraska, 2017-17

While Abbot Fuller Graves is best known for painting impressionistic gardens and landscapes, A New England Country Grocery was created while the artist was living and teaching in New England and demonstrates Graves’ engagement with the booming commercial market for nostalgic American genre scenes. Many of Graves’ compositions of small-town life were reproduced for American postcards and calendars, and this painting was reproduced as a print in 1897 for the Chase and Sanborn Coffee Company.

Both the subject matter of this picture and its nostalgic function relate to Electra Havemeyer Webb’s early visions for Shelburne Museum and its collections of American material culture. The contents of Graves’ interior are not unlike the chockablock rooms of A. Tuckaway’s General Store and Apothecary Shop, a repurposed building containing remnants of an imagined past that have been strategically reconstructed to create an evocative narrative for visitors.

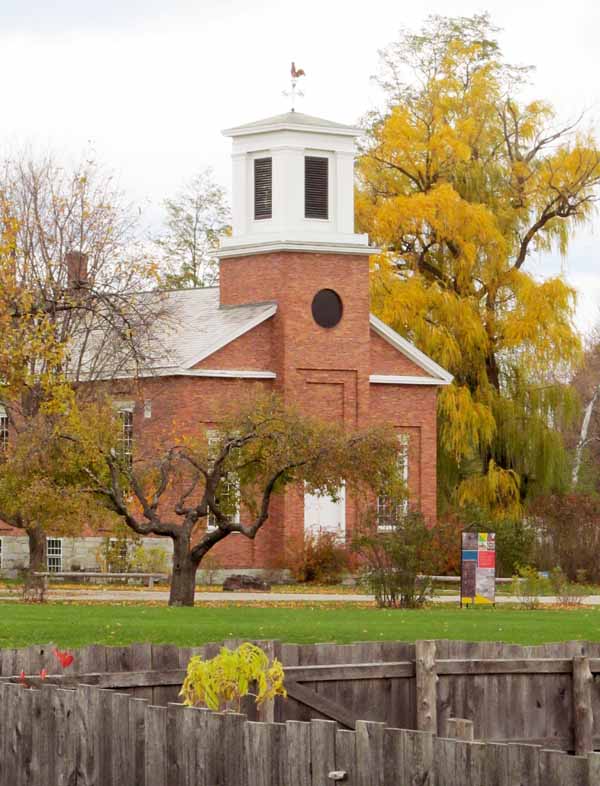

Charlotte Methodist Church (Charlotte, Vermont)

Meeting House, 1840

re-erected, 1952-55

Gift of Charlotte Library Association, 1950-80

Shelburne Museum’s Meeting House has been home to many communities over the years. The structure was originally erected in 1840 in Charlotte, Vermont, by the community’s Methodist congregation. By 1899, the building had ceased to function as a church and was taken over as a playhouse by an amateur theatrical group. In 1902, the group incorporated as the Breezy Point Library Association and bought the building to serve as the town library. A heavy windstorm damaged the building in 1950, and the association voted to move it to Shelburne Museum so it could be preserved.

In 1952, the building was dismantled and moved to the Museum grounds. Replacements for missing or damaged elements, including the belfry, pews and pulpit, were salvaged from an abandoned church in Milton, Vermont. The interior plaster walls were painted in tones of white and grey to resemble paneled woodwork. Today the structure serves as a reminder of the role of such gathering places in the religious, social, and civic lives of Vermonters. As an element of the Museum's campus, it continues to function as a site for performances, lectures, and meetings.

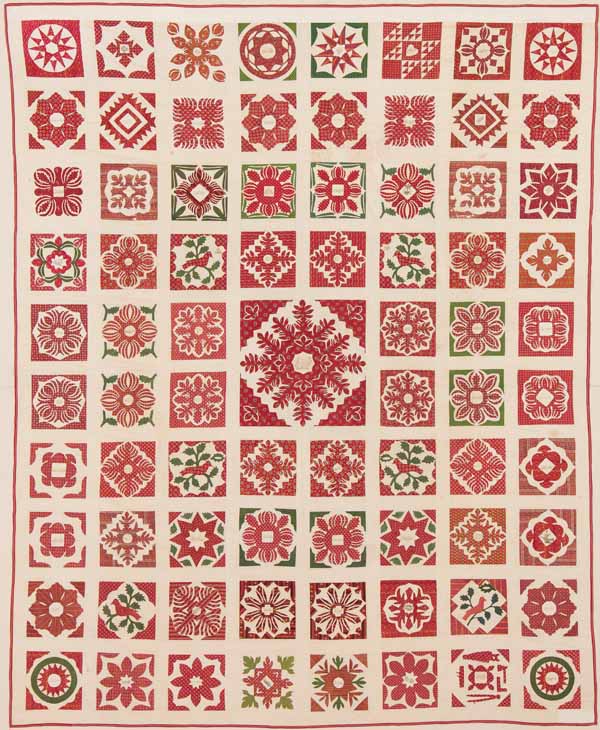

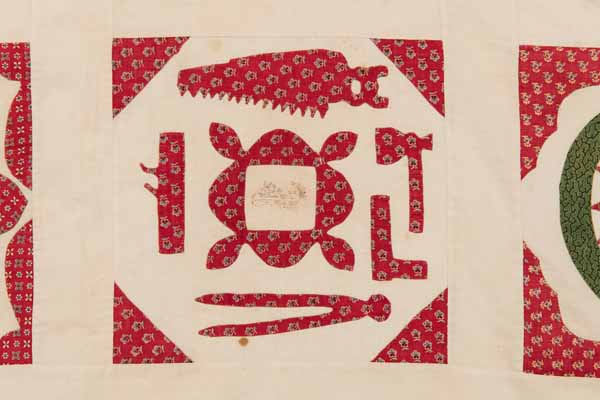

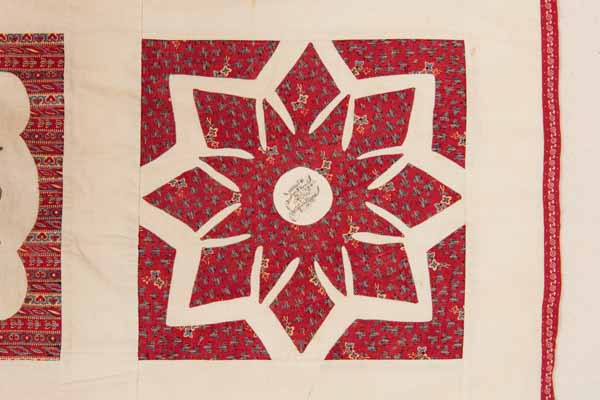

Made by the Family and Friends of John and Eliza Noble (Chester County, Pennsylvania)

Applique and Pieced Cutwork Friendship Quilt, 1847

Cotton and ink, 112 x 89 ½ in.

Gift of Jean Lovell, 2009-11

“Signature” or “friendship” album quilts were popular during the mid-19th century and were most commonly made to preserve and reinforce bonds of friendship, family, and faith. This quilt top’s center block reads, “John Noble, Eliza Noble, But for a being without end/ The vowd love we take/ Grant us oh God one home at last/ For our Redeemers sake 1847.” It was likely created to commemorate the 1847 marriage of John and Eliza Noble, members of a large Quaker community in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Research by textile historian Sandra Starley has revealed at least a dozen interrelated bedcovers made by this community. Ranging from simple pieced star patterns to the elaborate, appliqued cutwork in this example, these bedcovers employ similar printed cotton fabrics and feature the names of the same group of friends and family members. The consistent penmanship that defines the names, dates, and small, decorative icons like urns, doves, and foliate scrolls on this quilt top suggests that the hand of a professional calligrapher or scrivener may have added these details.

Elizabeth Mary Power Green (Keeseville, New York, 1822-65)

Pieced Old Italian Block Friendship Album Quilt, 1852

Cotton, silk, ink, and watercolor, 88 x 87 in.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Cecil Gilchrist, 1975-12

Thought to be constructed from silks and brocades salvaged from discarded garments, this exquisite quilt embodies" content="many of the Romantic-era themes of home, family, friends, nature, and death that inspired the creation of friendship album quilts during the mid-19th century. Family history relays that the quilt’s maker, Elizabeth Powers, sent the small pieces of silk cloth that make up the centers of the blocks to far-flung friends and relatives with requests for inscriptions.

Nearly all of the bedcover’s 81 blocks have been marked in ink with the names of Elizabeth’s friends and family or sentimental verses, and many are decorated in watercolor with delicate images of birds, hearts, bows-and-arrows, and other small icons. The quilt’s dedication block reads, “Friends have combined to form this valued spread / of beauteous pattern & varied shades / to join whole my needle has been true / in eighteen hundred fifty one and two / Elizabeth M. Green / Christmas, 1852.”

Unidentified maker (Possibly Midwestern United States)

Pieced Mennonite Star of Bethlehem Medallion Quilt, 1890-1900

Cotton

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Michael Polemis, 2006-13.8

This dynamic bedcover is thought to have been created in a Midwestern Mennonite community in the final decade of the 19th century. Mennonites are a religious sect that arose out of the Anabaptists, a radical reform movement of the 16th-century Reformation; the movement was named for Menno Simons, a Dutch priest who consolidated and institutionalized the work initiated by moderate Anabaptist leaders.

The radiating tones of this quilt’s central six-pointed star reveal careful planning and a deep familiarity with advanced quilting skills, hardly the work of an amateur. While it would be easy to romanticize this bedcover’s creation by a single maker, it is more likely that this quilt was constructed by a number of family or community members who all possessed specialized skills ranging from precise cutting of cloth, to piecing, quilting and finally, binding.

Unidentified maker (Lancaster County, Pennsylvania)

Pieced Center Diamond Amish Quilt, 1900-25

Cotton and wool, 78 5/8 x 76 ¼ in.

Museum purchase, 1988-52.1

The Amish are an American Protestant group descended from European Anabaptists who came to America in the late 18th century. Collectors and historians have lauded Amish quilts since the 1970s for their geometric design sense, liberal use of jewel-like fabrics, and carefully quilted feathers, scrolls, and other motifs—but what makes an “Amish” quilt “Amish,” anyway? Historian Janneken Smucker has argued that an “Amish” quilt is simply any quilt made or used by an Amish family. While there are no exacting rules for quilts made in Amish communities, common characteristics like pattern types or needlework themes have emerged in part because Amish codes of conduct tend to value conformity over individualism. The center diamond in a square featured on this bedcover is a pattern that is unique to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where the Amish first settled in the 1720s.

Unidentified maker (Mount Lebanon, New York)

Shaker Seed Box, 1861-88

Wood and paper, 3 ½ x 23 ½ x 11 ¾ in.

Museum purchase, 1949-117.36

The Shakers are a small Protestant religious denomination founded in Manchester, England in the mid-1700’s as a dissident group of the Society of Friends (Quakers). One of the Shakers’ most significant commercial industries was their seed business, first formed at the community in New Lebanon, New York around 1794. The Shaker formula for success was straightforward: find a product that consumers needed that was not readily available; make it convenient for customers to purchase and use; make it better than anyone else; and offer it at a fair price. Until the 1790s, seeds were usually sold in bulk to farmers; the Shakers’ innovative approach to packaging seeds in packets and boxes was aimed instead at consumers who wanted to plant modest kitchen gardens for home use. Seed envelopes and boxes could be purchased at general stores and usually offered a wide variety of vegetables. The earliest known surviving printed seed list, dated to the 1830s, included six varieties each of beets, peas, beans, and cabbages, plus seeds for 23 other vegetables. The seed box in Shelburne’s collection was likely produced between 1861—when the community of New Lebanon changed its name to Mount Lebanon—and 1888, when the business closed.

Molly Nye Tobey (Barrington, Rhode Island, 1893-1984)

Food for Liberty, 1942-45

Jute and wool, 40 x 147 in.

Gift of Joel N., Jonathan S. and Joshua A. Tobey, 1989-26.56

Encouraged by family and inspired by the everyday beauty of her New England community, Molly Nye Tobey began hooking rugs in 1907 at age 14. With a keen eye for detail, she went on to graduate from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1915. Soon after, she was admitted to the New Bedford Textile Institute—on the strict condition that she would not distract her male classmates from their work—becoming the school’s first female graduate in 1917. This same industrious work ethic and tireless drive propelled Tobey to continue creating and exhibiting her colorful hooked rugs well into the 1980s, until her death at age 91.

Tobey’s designs were colorful, lively, and often responded to current events. This rug was inspired by the “Victory Gardens” many Americans were encouraged to grow to help contribute to their own sustenance during World War II. After winning first prize and the Grand Award at the Woman's Day 1942 National Needlework Exhibition for this rug's design, Tobey was invited to appear as a guest on Mary Margaret McBride's popular NBC daytime radio program.