Like other institutions with similar collections, Shelburne Museum exhibits mechanical objects with moveable parts in static displays, frozen in both place and time. The reasons for this are twofold. First, most historical mechanical objects do not survive in good operational order because of broken or missing parts or other types of damage. Second, extant functional pieces are seldomly, if ever, activated to help preserve them in the best possible state for the benefit of posterity. Working closely with Shelburne Museum’s conservator, the items in this special online exhibition were carefully selected because of their good working and structural condition. Drawn from Museum’s circus, doll, folk art, and toy collections, these extraordinary objects represent the skills, creativity, and ingenuity of artists, manufacturers, and inventors from the past. The fact these objects survive in working order is a testament to both their makers and the people who played with them. Whether by turnkey, loaded spring, drawstring, or a gust of wind, the automatons, banks, toys, and whirligigs featured here come to life again for the first time in many decades to amaze, educate, and entertain contemporary audiences. Enjoy the shows.

Attributed to Pratt & Letchworth (Buffalo, New York, active 1826–1923)

Patent by Francis Carpenter (Port Chester, New York, active 1880–97)

Fire Escape, 1892

Cast iron and paint

Museum purchase, 2005-3.1

Francis Carpenter’s patented design for a string-operated Toy Fire Escape is an accurate replica of a burning brownstone building complete with firemen actively fighting the fire and rescuing a woman in distress on the second floor. According to his 1891 patent application, “the woman was to be depicted with the arms extended and the hands clasped in an imploring attitude. This enables those that play with the toy to place the figures upon the balcony in such a position that as the toy fireman is drawn up [the ladder]one of his arms will pass into the loop formed by the extended arms of the toy figure, so as to lift the toy figure off the balcony and suspend the same while the toy fireman and the figure are lowered to the ground, thereby affording amusement to those playing with the toy.”

The realism of Carpenter’s invention has been accurately captured in the exquisite manufacture of the toy by Pratt & Letchworth, premier toymakers in Buffalo, New York, which acquired Carpenter’s stock and patent rights in 1890. Period advertisements proclaimed Carpenter’s toy fire escape as “what all the boys who have a fire engine want.”

Shepard Hardware Company (Buffalo, New York, ca. 1882–92)

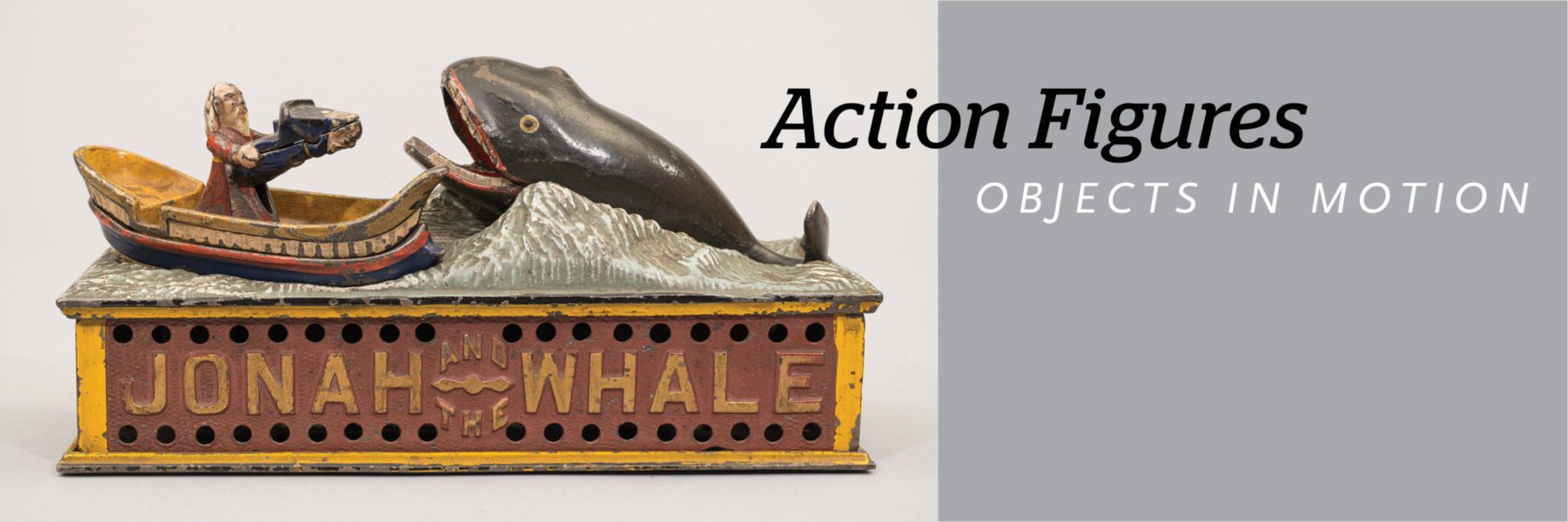

Jonah and the Whale Mechanical Bank, ca. 1890

Painted metal

Collection of Shelburne Museum, 22.4-11

Shepard Hardware Company (Buffalo, New York, ca. 1882–92)

Uncle Sam Mechanical Bank, ca. 1886

Painted metal

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb, 1947-17.3

The first chartered United States savings bank was established in 1819 in New York City, institutionalizing thrift as a national policy. Throughout the 19th century, the use of toy banks reinforced Benjamin Franklin’s (1706-90) earlier aphorism: “A penny saved is a penny earned.”

Although some banks were made of wood, glass, or pottery, by far the most common materials used between the Civil War and the turn of the century were tin-plate and cast iron. Banks were stationary (still) or moveable (mechanical) and took the form of buildings, animals, story characters, and famous people. Frequently, mechanical banks were designed to instill patriotism, teach morality lessons, or, unfortunately, trivialize political subjects or demean ethnic groups.

Unidentified maker (Possibly Pennsylvania)

Spinning Woman, 1875–1900

Carved and painted wood

Museum purchase, 1953, acquired from Edith Halpert, The Downtown Gallery, 1961-1.179

Nothing is known about the maker of this whirligig/trade sign or the business for which it was created. However, judging by the accuracy of the spinning wheel’s construction, it is clear the maker had some understanding of the technology used to spin yarn. The horizontal frame, with the drive wheel and spinning flyer located at opposite ends, is characteristic of the Saxon style of spinning wheel, which was developed in Europe in the 16th century and made familiar to 20th-century children around the world thanks to Walt Disney’s animated feature Sleeping Beauty. By incorporating slight modifications, such as flattening and angling the spokes of the drive wheel and adding a pinwheel propeller to the flyer to catch the wind, the maker was able to animate the moving parts of the spinning wheel, including the treadle, giving the impression that spinner’s foot is powering the device.

Unidentified maker (New England)

Swordsman Whirligig, 1870–1900

Carved and painted wood

Collection of Shelburne Museum, 1950-293

Whirligigs such as this maniacally smiling swordsman were designed to move in the wind. Equipped with fans, pinwheels, turbines, and in this case, blood-tipped swords, these whimsical kinetic sculptures were brought to life by gentle breezes, providing bursts of action and amusement.

Whirligigs come in a variety of forms, but soldiers, police officers, and other martial figures appear to have been especially popular subjects. The prevalence of such characters suggests that the amusement these toys offered was subversive, pitting figures of power and authority in futile battle against the wind.

Roy Arnold (Hardwick, Vermont, 1892–1976)

Age of Chivalry Tableau Wagon, Arnold Circus Parade, 1925–55

Carved and painted wood

Museum purchase, 1959-259.58

Inspired by the circus street parades he attended as a child growing up in Vermont, Roy Arnold dedicated 30 years of his adult life to the creation of his miniature model to preserve the pomp and pageantry of the now-extinct spectacles for the benefit of future generations. Made on a 1:12 scale, each of the 53 bandwagons and cage and tableaux wagons were replicated from old photographs and measured drawings of real parade vehicles used by all the major Golden Age American circuses. Although intended to be displayed stationary, Arnold’s miniature wagons were made with functional axels and wheels that are held in place by wheel chocks.

Featuring a princess riding on the back of a two-headed dragon and two knights in shining armor, The Age of Chivalry wagon (number 60 in Roy Arnold’s preferred layout of the model) was built in 1903 for Barnum & Bailey’s Circus by the Sebastian Wagon Company in New York.

Probably N. N. Hill Brass Company (East Hampton, Connecticut)

Trumpeting Elephant Bell Toy, ca. 1905

Nickel, iron, and paint

Museum purchase, 1956, 22.5-143

Equipped with a simple internal gear mechanism, this adorable cast iron elephant pull toy raises and lowers its trunk as its wheels roll across the floor. With each complete revolution of the wheels, the small brass bell held aloft at the tip of its trunk rings as it hits the small triangular-shaped striker that protrudes from the outwardly curved portion of the pachyderm’s proboscis.

Along with mechanical banks, wheel-driven pull toys were among the most popular types of playthings produced during the heyday of America’s cast iron toy industry from the late 1860s to the early 1900s. As a material for toy making, cast iron became popular after the end of the Civil War as foundries retooled from armaments production to the manufacture of domestic goods.

Unidentified maker

Construction Crew at Work, date unknown

Carved wood

Gift of Electra Havemeyer Webb, 1954-162.4

By twisting the wood dowel located on the proper left of the base, the operator becomes the foreman of this whimsical construction site, controlling every move of the four-man carpentry crew building this balloon-frame style house. Each of the workers has an articulated right shoulder joint connected to a hidden internal system of wires governed by a gear and trip wheel mechanism. Each turn of the dowel raises and lowers the men’s right arms that hold different tools of their trade, instigating the sawing of lumber, hammering of nails, and the layering of roof shingles.

Fernand Martin (Paris, France, 1849–1919)

The Mysterious Ball, late 19th–early 20th century

Painted tin with lithography

Gift of Mrs. Helen Bruce, 22.2.3-69

This string-operated toy was inspired by the famous, death-defying Mysterious Ball circus act, popularized by French daredevil Leon LaRoche around the turn-of-the-20th century. Combining the agility of an acrobat with the flexibility of a contortionist, LaRoche encapsulated himself in a large metal globe that he propelled up a twenty-four-foot-tall spiral ramp by shifting the position of his body weight inside. After reaching the apex of the ramp, a gun shot prompted LaRoche to pop out of the orb holding two flags before making his rolling descent. The popularity of the Mysterious Ball Act spiraled out of control, inspiring a host of imitators, including performers who ascended helical ramps by either balancing on large rolling balls or riding unicycles or bicycles.

Unidentified maker

Squirrel Cage, ca. 1900

Carved and painted wood

Museum purchase, 1952-1252

An elaborate ancestor of the modern hamster wheel, this brightly painted squirrel cage incorporates different kinetic actions into its design. When a squirrel ran in the cylindrical cage, the turning wheel powered the mechanisms of the figures operating the saws on top, causing them to rise up and down in a sawing motion. The two boxes on either side of the cage, painted to resemble Georgian townhouses, would have served as nesting areas for the squirrel.

Squirrels were kept as pets in Europe and America in the early 18th and 19th centuries (hamsters were not introduced to the United States until the 20th century). Several elaborate squirrel cages survive, often in the form of miniaturized houses, though Shelburne’s example is unusual in its mechanical complexity.

Unidentified Maker

Clown Magician Automaton, France, ca. 1880

Papier-mâché, paint, glass, wire, wood, paper card stock, molded cardboard, cheesecloth, linen, leather, velvet, silk, cotton jersey

Museum purchase, 1961-1.34

Wearing a grin and a slyly arched eyebrow, this clown magician invites us to a game of illusions. When fully wound, he taps his wand and raises his hat to reveal a chicken, a frog, and other surprises, all of which are stored on a rotating carousel located underneath the game table.

While an automaton can refer to any self-operating mechanism, the term most frequently describes animal or anthropomorphic figures intended for entertainment. Automata designs date to antiquity, but they reached their apex in popularity and diversity during the late 19th century, when industrialization enabled the mass production of the mechanical parts required for these machines. French automata, such as this clown magician, were especially revered for their high quality, and required the collaboration of clockmakers, sculptors, painters, and other artisans.