Nancie Ravenel, Director of Collections & Conservation

Last summer, one of my colleagues, Landis Smith, created an experience for me, and by extension, the collection, that has profoundly impacted my understanding of Pueblo pottery and its care.

Smith, who is Projects Conservator at the Museums of New Mexico Conservation Unit, working primarily with the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, is a widely acknowledged and highly regarded expert in the conservation of Native American works, especially those from Pueblo communities. Over the years, she has built longstanding relationships with artists, thinkers, and leaders in these communities, and has collaborated with members of Native communities and museum professionals to create guidelines for the ethical care of Indigenous cultural material that inform my own work.

After the pots displayed in the 2023 exhibition Built from the Earth arrived at Shelburne Museum, I consulted with Smith to examine them with me, first virtually and then in-person in Shelburne. During her visit, she pointed out condition issues typical of utilitarian usage, evidence of past restoration, and condition issues that should be investigated further, offering greater context than what I could obtain on my own.

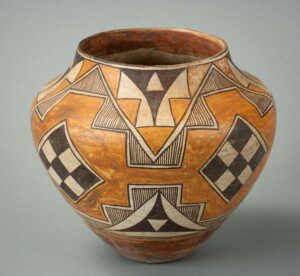

At her invitation, I made a trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Together, we visited the Museum of American Indian Art and Culture to visit pots in storage so that I could examine a wider range of art from Pueblo communities than what we have at Shelburne Museum, more examples of evidence of use, examples of condition issues, varied approaches to repair, and housing methods. Because she could vouch for my sincerity and approach, and owing to the strength of her relationships, I was able to meet and have extended conversations with several artists and culture bearers. Potters from the San Ildefonso and Acoma pueblos welcomed me into their homes and shared stories about how they learned their craft and how pots attributed to them individually are, in fact, the product of a number of hands who assist with gathering and processing their materials. Family members and assistants help dig and transport clay and slip materials from nearby locations. They forage truckloads of beeweed, sometimes referred to as spinach, that gets cooked down to make organic paints. These trips are times when stories are shared, and traditions are passed along. With a group of local conservators, I was able to watch the San Ildefonso potter and his assistant fire pots outdoors using cow and horse manure to fuel the fire and ask questions about their experiences with factors that influence a pot’s appearance and longevity.

Perhaps the most impactful experience for me was the opportunity to visit the Puye Cliff Dwellings with museum, cultural preservation and language program consultant Tessie Naranjo and her niece, artist Eliza Naranjo Morse. Both are members of Santa Clara Pueblo, and Puye is their ancestral home. We joined another guided group exploring the site. The guide invited group members to respectfully examine pot sherds and rocks shaped into tools found at the site and pointed out features of the site that supported the community’s life on the Pueblo, including partly restored summer and winter dwellings constructed of wood and soft volcanic tuff and the narrow steps worn into the side of the mesa. While I greatly appreciated the opportunity to look closely and handle these pieces of the past, it was truly an honor to hear Naranjo and Naranjo Morse’s perspectives about the site and efforts to preserve their culture and language and watch how they interacted with the landscape, structures, pot sherds, and tools with deep respect and appreciation.

I am deeply appreciative to Landis Smith for these experiences. Honoraria paid to those I visited during the trip were funded in part by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Save America’s Treasures program.